WASHINGTON, DC, March 29, 2022 (ENS) – Turning coal waste from power plants into fire-resistant, strong, lightweight building materials is a project the U.S. Department of Energy is supporting, investing another $2.2 million this month as part of a wider effort on the part of the Biden administration to find ways of easing the impact of the nation’s switch from fossil fuels to clean energy on coalfield communities.

The $2.2 million is going to X-MAT Carbon Core Composites LLC, of Orlando, Florida, a division of Semplastics, located nearby. In 2013, the Advanced Materials Division of Semplastics began development of a new high performance material utilizing coal, now called X-MAT®, that the company claims “combines the most valuable properties of metals, plastics and ceramics.”

X-MAT CCC has been awarded the $2.2 million in a follow-on contract from the DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory, NETL, to continue the research and development of its high-strength, lightweight building materials made using domestic coal.

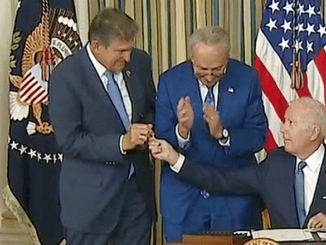

The company will continue the process of creating a building made entirely from coal-based materials – from structural columns to walls to roof tiles. “These coal-derived building materials are fire resistant, non-toxic, lightweight and durable, making them not only safer than their traditional counterparts, but easier to use and eco-friendly,” the company says on its website.

“This is coal reimagined,” said Bill Easter, founder of X-MAT and Semplastics. “We’re honored to receive this funding from the DOE to continue the revolutionary work of using coal and coal waste to bring these innovative, green building products to the marketplace.”

In total, the NETL has awarded X-MAT® and Semplastics over $13 million in grants and contracts, including a $1.4 million contract to create new uses for coal waste and a nearly $1 million contract to help fund research on utilizing coal in battery materials.

“The research we’re conducting today is crucial for the long-term viability of coal,” said Easter. “It could one day be used to generate thousands of jobs in West Virginia and other coal regions.”

The prototype structure to test these coal-derived building materials is going up in Bluefield, West Virginia, U.S. Senator Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat who chairs the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, said with Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm at Marshall University on March 18.

The company hopes to have a partial coal house constructed by 2023 using its proprietary roof tiles, siding panels, bricks, and blocks.

“There are so many fascinating, ecofriendly ways to use and recycle coal,” said Easter. “Our team has already reimagined coal in unique ways such as the X-TILE™, a lightweight, fireproof coal roof tile that can withstand extreme temperatures. Building a house almost entirely from coal is next on our docket. We’re very thankful to the DOE for its continued support of our work.”

Coal Waste Makes Its Mark in 3-D Printing

The Department of Energy is also investing in a project at the University of Delaware to find efficient, effective ways to use graphene particles from domestic coal wastes in 3D printing.

Professor Kun “Kelvin” Fu in mechanical engineering and Professor Feng Jiao in chemical and biomolecular engineering will spend the next three years working with students on converting coal to a carbon material, which can then be added to filaments or resins used to feed high-tech 3D printers.

Their research is funded by $1 million from the U.S. Department of Energy, with another $250,000 in funding from the University of Delaware.

“Right now, the Department of Energy is looking for new technologies to neutralize coal as a carbon feedstock,” Jiao said. “We cannot keep burning coal. But we can use coal as a feedstock to produce other useful substances that don’t involve a lot of harmful emissions.”

As the climate community urges countries and industries around the globe to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, there’s also the reality that industrial operations cannot be immediately shut down. That includes coal mining.

“If we convert coal to a carbon material and use it for 3D printing, that’s a way to neutralize the coal feedstock, but still keep jobs and create high-value products,” Jiao said.

And the long-game is what it’s about, he explained, noting that this isn’t typically the kind of research project he’d work on — and it will be his first with Fu. Coal is messy and full of contaminants and trace metals, which is why it’s not typically thought of as a good feedstock of the filaments needed to create 3D-printed materials. By deriving graphene particles from domestic coal wastes, the carbon content of the filaments used for printing can also be increased.

The benefits of 3D printing have bloomed in recent years. Modern printers using plastics and other materials can create everything from prosthetics to vehicle parts to homes. Using coal byproducts as a low-cost source material in manufacturing a variety of higher value products could have wide-ranging market benefits.

Not only could their work find an alternative use for coal waste, but it also could lead to future 3D printing applications in lightweight vehicles, which play a key role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, which accounts for 10 percent of global emissions.

If this project is successful, it would allow the printing of vehicle components, such as bumpers, especially for electric vehicles, Professor Fu said. The material, made by coal-derived graphene and plastics, could even be altered to increase the electrical conductivity of filaments for applications that require electrical connections.

Six other universities and organizations also received millions in DOE funding to explore additive manufacturing alternatives involving coal-derived materials.

“We desperately need more new technologies that can make these manufacturing processes more sustainable while also making high-value materials that don’t have an impact on the environment,” Jiao said.

Coal Waste is Dangerous

Beyond emitting 1.9 billion tons of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide each year, coal-fired power plants in the United States also create 120 million tons of toxic waste. That means each of the nation’s 500 coal-fired power plants produces an average 240,000 tons of toxic waste each year.

According to EPA, coal ash is disposed in over 310 active on-site landfills and 735 active on-site surface impoundments.

Coal ash contains contaminants like mercury, cadmium, chromium, lead, and arsenic, warns the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Without proper management, these contaminants can escape from containment ponds to pollute waterways, groundwater, drinking water, and the air.

In March 2019, a report jointly published by the Environmental Integrity Project and the law firm Earthjustice found that the “vast majority” of 250 U.S. coal ash ponds had leaked chemicals into nearby groundwater. More than 90 percent of the nation’s coal-fired power plants reported elevated levels of toxic pollutants in these groundwater sources, levels that often exceed the limits established by the EPA.

Human exposure for a short time can irritate the nose and throat, and cause dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and breathing troubles. Long-term exposure can lead to liver or kidney damage, cardiac issues, and cancers.

Currently, state environmental agencies are primarily responsible for regulating beneficial use.

EPA explains that the beneficial use of coal ash must meet four criteria – provide a functional benefit; substitute for the use of a virgin material; meet product specifications and/or design standards; and when 12,400 tons or more are used in non-roadway applications, the user must demonstrate that environmental releases to groundwater, surface water, soil, and air are comparable to or lower than those from similar products made without coal ash, or that releases will be below regulatory and health benchmarks for humans and the environment.

Featured image: Artist’s rendering of a house made entirely of building materials derived from coal. (Image courtesy X-Mat)