FARMINGTON TOWNSHIP, Pennsylvania, November 19, 2021 (ENS) – In 2017-18, Farmington Township, a community of about 2,000 in northwestern Pennsylvania became what resident Siri Lawson calls “ground zero” in the debate over using public dirt roads for oil and gas wastewater disposal. The wastewater is damaging the roads, and residents fear toxic chemicals in the wastewater are making them sick and poisoning the environment.

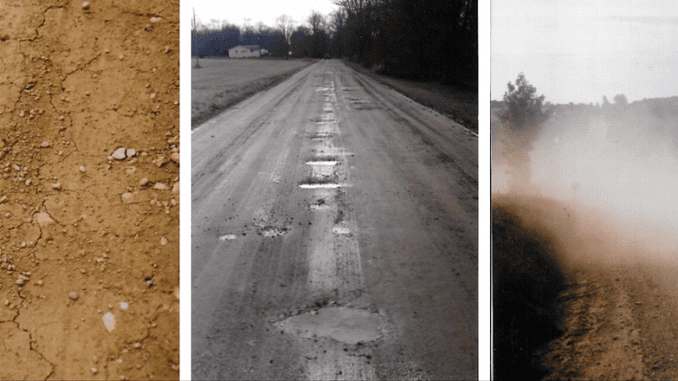

“Our township roads have become brine dumpsites, and the practice continues,” writes Lawson in the current issue of “PA Environment Digest.” She writes, “The excessive, repetitive, sanctioned road spreading causes Township roads to physically, mechanically and chemically change and break down.”

“Experts say this means brine has destabilized the road,” writes Lawson. “Locals say the roads had ‘lost their base.'”

There are 44 miles of dirt roads in rural Farmington Township, used by horse-drawn Amish buggies as well as cars and trucks. In summer, Amish children walk barefoot on these roads.

Over about the past 10 years, tanker trucks have been spreading thousands of gallons of salty wastewater brine from gas and oil well drilling, or from fracking, onto those dirt roads.

Supervisors of the township told the “Pittsburgh Post-Gazette” back in 2016 that their constituents want them to keep road dust down for health and aesthetic reasons, and the tanker truck spraying is an inexpensive way to do that. They don’t have to pay the two companies that apply the wastewater.

But many Amish people who live beside and travel the dirt roads, and their “English” neighbors, have signed petitions to the supervisors asking that the township stop the wastewater spreading. They complain that excessive spreading of briny liquids is sickening residents, polluting streams and farm ponds, making the roads slimy and dangerous to drive, and rusting out vehicles.

Lawson has warnings that are even more dire. “Any brine from any geologic layer is not just metals and salts. There is an alphabet soup of hazards in freshly spread brine,” she writes.

“Volatile organic compounds, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene, Diesel Range organics, frac fluid, production chemicals, stimulation chemicals, biocides, well maintenance chemicals all find their way into conventional oil and gas drilling wastewater,” writes Lawson, who fears that the wastewater could be “dangerously radioactive.”

The Natural Resources Defense Council, NRDC, is also warning about radioactivity in fracking wastewater in a report released in July, “A Hot Fracking Mess: How Weak Regulation of Oil and Gas Production Leads to Radioactive Waste in our Water, Air and Communities.”

“Oil and gas extraction activities, including fracking, drilling, and production, can release radioactive materials that endanger workers, nearby communities, and the environment. Radioactive elements are naturally present in many soils and rock formations, as well as in the water that flows through them. Oil and gas exploration and production activities can expose significant quantities of these radioactive materials to the environment,” the NRDC reports.

“Road spreading would generate a massive accumulation of toxic mud on vehicles, Amish buggies, even bare feet,” writes Lawson. “Amish and English alike reported that chisels were needed to remove the toxic caked muck.”

“We residents knew dust would begin to blow again even before freshly spread brine was even dry. Often in as little as an hour. The fossil fuel industry as well as regulators used this evaporative phenomena as an excuse to dump more oil and gas wastewater. It became a self-perpetuating cycle,” Lawson writes.

“Through science we now know the ions in the road material and the ions in the oil and gas wastewater actually push each other apart and destabilize the road creating dust and more runoff into ditches and streams than would normally occur,” she explains.

Now, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is in the lengthy process of deciding what to do about this method of oil and gas wastewater disposal. The EPA’s projections show that the volume of wastewater will only increase.

In its latest report on oil and gas wastewater management, issued in May 2020, EPA says that stakeholders raised concerns regarding additional discharge options for treated produced waters.

“The main concerns were related to the amount of available data on the chemistry of produced waters and the performance of treatment technologies,” the EPA said in the report.

A related concern was the availability of analytical methods for measuring the constituents in produced water, and the potential toxicity of these constituents. Stakeholders were also concerned about potential impacts to downstream users, such as impacts to drinking water utilities.

The agency said, “These are considerations that are important as the EPA considers next steps for its CWA [Clean Water Act] programs related to produced water management.”

Featured image: Dirt road in Farmington Township, Pennsylvania shows the cracking effects of oil and gas wastewater spraying, left, the potholes left as the road deteriorates further, and blowing dust carrying toxic materials from the wastewater. (Photos by Siri Lawson)