By Benjamin Seidman

CHESAPEAKE BAY, Maryland, February 11, 2022 (ENS) – In the eternal struggle between the ebb and flow of tides, high tides now have the upper hand as the sea is encroaching on land, rising as the climate warms. As the sea-level rises, valuable coastal wetland ecosystems are being lost to the sea due to salt poisoning.

Coastal wetlands are constantly saturated with salt water and plants that live there have adapted to harsh, ever-changing environments. These wetlands flourish in coastal watersheds at or just above sea-level and include a variety of ecosystems – fresh and saltwater marshes, seagrass beds, mangrove swamps, and forested swamps.

A debate about how coastal wetlands are likely to react to the rising sea levels is ongoing, with experts in wetland salinization arguing on both sides of the issue.

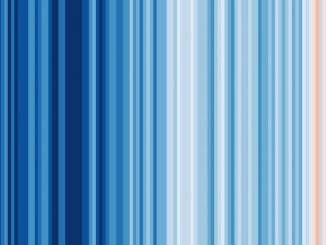

Matt Kirwin, associate professor of coastal landscape evolution at Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, believes that many marshes will be able to retreat to higher ground. As evidence, he points to ghost forests whose trees were killed by saltwater intrusions.

These ghost forests have now been replaced by more salt-tolerant marsh environments where tree stumps, remnants of the lost low-lying forest, are littering the ground.

Critics of this idea include Torbjörn Törnqvist, a professor of geology at Tulane University in New Orleans who researches coastal resilience and sea-level change.

“This idea of wetlands expanding under accelerated sea-level rise, it basically violates some of the most basic geologic theory. It’s just not going to happen,” Törnqvist told “Science,” a news journal published by the nonprofit American Association for the Advancement of Science.

His research has found that over shorter periods, wetlands can keep pace with rates of sea-level rise of up to one centimeter per year, more than double the current rate. But in the multidecadal time scale, marsh ecosystems appear to collapse at far lower rates of sea-level rise.

Others argue that even if marshes can outpace the rate of sea-level rise, this retreat of the marshes is not possible in many places due to human barriers such as levees, seawalls, and buildings.

According to the Georgetown University Climate Center, “As sea-levels rise, wetlands are encountering physical barriers to inland migration – a phenomenon known as coastal squeeze. Wetlands are being squeezed between sea-level rise on one side and human development on the other.”

Mountains, too, prevent the retreat of marshes, a problem on the west coast where the coast range often allows for little to no movement of marshes that are unable to climb hills.

Where marsh migration does occur, salt marshes eat into important agricultural lands or low-lying wetland forests, creating problems for people and the ecosystems they invade. Thousands of acres of agricultural land on the east coast, near Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay, already have been abandoned due to salt intrusion.

Eric Bedworth, a soybean farmer from the area who lost a field to salt intrusion, told the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, “I hate to see the land go out of production. But I’ve lost so much money down there.”

This has become a common struggle for farmers in the region and will only worsen in the coming years as more fields are claimed by marshes.

“It’s an issue that’s here and going to stay and we’re going to have to live with it,” Bob Fitzgerald, another farmer from Somerset County who lost land to the rising waters, explained to the Howard Center.

Salt marshes in protected areas often have protected low-lying forested wetlands behind them. When marshes are forced to higher ground, they can damage these areas which cannot tolerate the increased salt, damage that produces ghost forests.

A new study published by Duke University, which examined plants in coastal forested swamp environments in the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula of North Carolina, concluded that many of the 112 marsh plants studied are unable to survive when concentrations of salt in the soil exceed newly identified “tipping points.”

When these critical thresholds are crossed, the low-lying forested environments change as many plants die off and are replaced by other plants better able to handle saline environments.

“We saw that when you reach 265 micrograms of sodium per gram of soil, 44 percent of salt-sensitive species were no longer observed at those higher salt concentrations. That’s a lot. That was surprising to me – that there would be that many species that were not growing, or not abundant in sites with salinity above that amount,” said Marcelo Ardón, co-author of the study, in an interview with North Carolina State University.

The North Carolina study indicates that the collapse of coastal wetland environments due to saltwater intrusion may occur faster than previously thought, posing a critical threat to low-lying forests that couldn’t retreat as effectively as marshes.

This study will provide a future barometer of change without the need for intensive surveying.

When rushes and poison ivy become abundant, salt stress is often the source for this change.

The study’s lead author, Duke University researcher Steve Anderson, focused on coastal ecosystem resilience. “This could be a beneficial way of looking at areas that are changing because of sea-level rise. We can use our findings to pinpoint areas that maybe need a little more investment, and some of our other work is looking at how the low levels of salinity alter tree physiology. This is helpful as we consider what plants may be best for restoration.”

Coastal wetlands have long been dismissed as unproductive, bug-ridden lands. Only recently have they begun to get the credit they deserve as biodiversity epicenters.

U.S. coastal wetlands support mangroves and grasses which create essential habitats and breeding grounds for fish and birds that are adapted to these unique environments.

Wetlands filter excess nutrients, sediments, and pollutants out of rivers and trap them in the soil before they reach the ocean. With their slow rate of decomposition and high rate of growth, healthy wetlands can sequester atmospheric carbon, trapping it in the soil, and in doing so, slowing global warming.

Studies have shown that coastal wetlands sequester carbon at 10 times the rate of their tropical forest counterparts.

Protecting coastal wetlands is important economically. Wetlands can act as buffers defending infrastructure from flooding in storms by reducing wave heights and soaking up much of the storm surge.

More than half of the commercially caught fish and shellfish in the southeastern United States depend on coastal wetlands.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has awarded over $20 million in grants for healthy coastal wetlands projects, with another $17.6 million added on by tribal and local governments, private entities, and conservation groups.

In Anne Arundel County, Maryland, the Tizzard Island Shoreline and Marsh Resilience Restoration is underway. This project aims to make a more resilient coastline and protect the tidal marsh, which supports saltmarsh sparrows, other migratory birds, and waterfowl. This project is supported by over $2 million in grants and additional funding.

These funds will be put to use on 25 projects, like the restoration on Tizzard Island, to conserve and restore 61,000 acres of coastal wetlands across 13 states. 61,000 acres amounts to less than the annual loss of coastal wetlands in the United States.

The grants awarded for the conservation of coastal wetlands in 2022 reflect the importance of preserving wetlands facing mounting threats from salt stress.

Featured image: A ghost forest on Capers Island, South Carolina. (Photo courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA)