TUSAYAN, Arizona, August 10, 2023, (ENS) – President Joe Biden has established a new national monument to protect three areas close to Grand Canyon National Park that the President said, “have been profoundly sacred to Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples of the Southwest since time immemorial…”

Encompassing nearly a million acres in northern Arizona, the new Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument is also known for its natural resources, such as uranium, as well as its cultural, economic, scientific, and historic resources, and for its vast recreational opportunities.

The new monument is named as the surrounding Tribes call it. “Many of the Indigenous names for the area reflect the deep interconnection between the land and its Tribal Nations,” President Biden said, announcing the new monument with Tribal leaders and members of Congress in front of Red Butte, Arizona, a feature of the monument.

Baaj Nwaavjo means “where Indigenous peoples roam” to the Havasupai Tribe, and I’tah Kukveni means “our ancestral footprints” in the Hopi language.

In designating the new monument, President Biden proclaimed that these landscapes are “more than the mere sum of their parts, and thus the entire landscapes within the boundaries of each area reserved by this proclamation are themselves objects of historic and scientific interest in need of protection under section 320301 of title 54, United States Code,” the Antiquities Act.

The monument designation withdraws the entire 917,618 acres from any new sale or lease, barring any uranium mining, an issue of deep concern to residents of the area.

Former President Barack Obama banned new uranium mines in the Grand Canyon area in 2012, but this policy was scheduled to expire later this year.

The official proclamation establishing the new monument states, “All Federal lands and interests in lands within the boundaries of the monument are hereby appropriated and withdrawn from all forms of entry, location, selection, sale, or other disposition under the public land laws or laws applicable to the Forest Service, other than by exchange that furthers the protective purposes of the monument; from location, entry, and patent under the mining laws; and from disposition under all laws relating to mineral and geothermal leasing.”

In his proclamation, President Biden said the monument designation is “necessary.”

After a lengthy listing of the unique characteristics of the three areas reserved in the monument, Biden said, “I find that there are threats to the objects identified above, and, in the absence of a reservation under the Antiquities Act, these objects are not adequately protected by the current withdrawal, administrative designations, or otherwise applicable law because current protections do not require executive departments and agencies to ensure the proper care and management of the objects, and some objects fall outside of the boundaries of the current withdrawal; thus a national monument reserving the lands identified herein is necessary to protect the objects of historic and scientific interest identified above for current and future generations.”

The Biden Administration is now beginning to deal with the environmental mess left by uranium mining in the area. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, on March 29, 2023, proposed to add the Lukachukai Mountains Mining District on the Navajo Nation in northeast Arizona, contaminated by previous uranium mining activities, to the Superfund List, making it a cleanup priority.

The Lukachukai Mountains Mining District contains more than 100 waste piles from uranium mining operations that occurred from the 1940s through the 1980s. During that time, the now defunct company mined more than seven million tons of uranium ore, leaving behind a toxic legacy that poses ongoing threats to human health and the environment in the area.

The mining waste is contaminated with radium 226, uranium and other heavy metals. The Lukachukai Mountains are home to the Navajo people and they use the area for hunting, plant gathering, and livestock grazing. The mountains provide habitat for sensitive species, including the federally threatened Mexican spotted owl.

Waste from these piles has migrated downstream and may have impacted groundwater, the EPA warns. The wide-spread contamination “requires a coordinated effort to ensure cleanup of all former mining areas and to address downstream impacts,” the EPA says.

For years, the leadership of the Navajo Nation has advocated for cleanup and remediation of abandoned mine sites. “This is monumental for the Navajo Nation communities of Cove, Red Valley, Lukachukai, Round Rock, and the whole Navajo Nation,” Cove Chapter President James Benally said in a statement. “This will help address the legacy of abandoned uranium mine sites on our sacred mountain. We welcome it, on behalf of our grandchildren and generations to come.”

Management Plan to Include Tribal and Public Input

The monument lands will continue to be managed by the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, BLM, and Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service.

The Forest Service shall manage the portion of the monument within the boundaries of the National Forest System as part of the Kaibab National Forest. The BLM shall manage the remainder of the monument as a unit of the National Landscape Conservation System.

The monument designation honors valid existing rights and does not apply to private property or Tribal, state or local government lands, the Department of the Interior states.

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland is delighted with the new monument, saying, “Today’s action by President Biden makes clear that Native American history is American history. This land is sacred to the many Tribal Nations who have long advocated for its protection, and establishing a national monument demonstrates the importance of recognizing the original stewards of our public lands. Indigenous Knowledge is a core piece of what we mean when we talk about collaborative conservation.”

“Today, I am honored to stand with the President, Tribal leaders, and local communities and coalitions that made it possible,” said Secretary Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe and the first Indigenous person to serve as a Cabinet secretary.

Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, who will manage the monument with Secretary Haaland, said, “Today’s designation safeguards a treasured piece of our national heritage for this generation and generations to come. President Biden’s action honors the commitment of the Indigenous peoples that have long held this place sacred and preserves the area’s important historic, scientific, natural and recreational benefits for all Americans.”

From now on these lands are protected, as the proclamation makes clear, stating, “Warning is hereby given to all unauthorized persons not to appropriate, injure, destroy, or remove any feature of the monument and not to locate or settle upon any of the lands thereof.”

The secretaries are tasked with jointly preparing a management plan for the monument, and to make rules and regulations to carry it out. They are directed to consult with other federal land management agencies such as the National Park Service, with local and State governments, with the Tribes, and with the general public and provide for “maximum public involvement in the development of the management plan.”

In the development and implementation of the management plan, the Secretaries shall, “carefully incorporate the Indigenous Knowledge or special expertise offered by Tribal Nations and work with Tribal Nations to appropriately protect that knowledge.”

And the proclamation directs the secretaries to “explore opportunities for Tribal Nations to participate in co-stewardship of the monument.”

The management plan is expected to “maintain the undeveloped character of the lands within the monument; minimize impacts from surface-disturbing activities; provide access for livestock grazing, recreation, hunting, fishing, dispersed camping, wildlife management, and scientific research; and emphasize the retention of natural quiet, dark night skies and scenic attributes of the landscape,” the proclamation directs.

Tribes Originally Proposed the Monument

The Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument includes the homelands of at least 11 Indigenous Tribes, Nations, and Tribal Associates, many of them represented in the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition.

After accepting an invitation from Ranking Member Grijalva, U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland visited the Grand Canyon region in May to engage with members of the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, stakeholders, and federal agency officials on the national monument proposal.

They agree that protecting the area from uranium mining will help safeguard underground aquifers and critical drinking water supplies for nearby communities and the entire Colorado River Basin.

The monument was proposed in April by a large group of Tribes known as the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition. The coalition consists of leadership representatives of 13 Tribes: Havasupai Tribe, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, Kaibab Paiute Tribe, Las Vegas Band of Paiute Tribe, Moapa Band of Paiutes, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Navajo Nation, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Shivwits Band of Paiutes, Yavapai-Apache Nation, Pueblo of Zuni, and the Colorado River Indian Tribes.

“The creator gave us a gift, and that gift is in the form of the Grand Canyon,” Hopi Tribe Chair Timothy Nuvangyaoma told the Grand Canyon Trust, an NGO that supports the monument. “That gift is not only to the tribal nations that have that intimate connection with it, but it’s a gift to the state of Arizona, it’s a gift to the United States, it’s a gift to the entire world.”

For years, the tribes have called for the permanent protection of these lands with a national monument designation.On April 11, 2023, the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, joined by Ranking Member Grijalva, re-launched their effort, calling on President Biden to designate the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument.

Naturally, the monument has the support of nongovernmental organizations that have a wider membership than tribal members.

“The Grand Canyon is one of the crown jewels of the West, and it is now better protected for future generations thanks to the historic advocacy of the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition,” said Jennifer Rokala, executive director of the nonprofit, nonpartisan Center for Western Priorities based in Denver, Colorado.

“Today’s designation of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument is a historic event,” she said. “President Biden has honored Tribes and safeguarded critical drinking water supplies for Tribal communities as well as the entire Colorado River Basin.”

“Today’s designation moves the country closer to the Biden administration’s goal of protecting 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. I’m grateful to President Biden for his strong commitment to conservation and urge him to continue using his power under the Antiquities Act to protect imperiled ecosystems and other important natural areas,” Rokala said.

In his proclamation, President Biden acknowledged, “The history of the lands and resources in the Grand Canyon region … tells a painful story about the forced removal and dispossession of Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples. The federal government used the establishment of Grand Canyon National Park to justify denying Indigenous peoples access to their homelands, preventing them from engaging in traditional cultural and religious practices within the boundaries of the park.”

“Despite these barriers,” Biden said, “Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples persevered and continued to conduct their long-standing practices on sacred homelands just outside the boundaries of the national park, among the vast landscapes of plateaus, canyons, and tributaries of the Colorado River.”

Buu Nygren, President, Navajo Nation said today, “The Grand Canyon is too important to not protect…. We are thankful to President Biden and the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition for their efforts in pushing this initiative to protect our people from the adverse effects of uranium mining.”

Monument Draws Bipartisan Support

The day the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition proposed the monument, April 11, they were joined by U.S. House Natural Resources Committee Ranking Member Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat, and U.S. Senator Kyrsten Sinema, newly switched to Independent from Democrat, both of Arizona.

Not always on President Biden’s side politically, Senator Sinema is proud that she “championed and celebrated the designation of a new Grand Canyon National Monument with U.S. President Joe Biden, Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs, U.S. Representative Raúl Grijalva, and Tribal and local leaders from across Arizona,” she said in a statement today.

Earlier this year, Sinema and Grijalva introduced the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument Act, legislation establishing over a million acres of federal lands as a new national monument in northern Arizona.

“Today’s designation is the product of hard work and relentless determination of thousands of Arizonans from diverse backgrounds and interests, including Arizona tribal communities, local leaders, conservationists, sportsmen, and many more,” Sinema said, “all with a shared passion for protecting Arizona’s air, land, and water for future generations.”

She says a recent survey found overwhelming bipartisan support among Arizonans for the new national monument.

“Thanks to the tireless efforts of the tribes – the original guardians and stewards of the Grand Canyon – we are witnessing the culmination of a monumental journey,” said Ranking Member Grijalva. “Designation of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument is a remarkable triumph and a testament to the unwavering dedication of the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, local communities, and other allies. Together with the Biden-Harris administration, we’re ensuring the protection of the region’s vast and rich natural resources, safeguarding cultural heritage, and preserving the incredible beauty of this iconic landscape for generations to come.”

“Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument is broadly supported by Arizonans across party lines and has long been a priority for sportsmen and sportswomen in the state,” said Nathan Rees, Arizona Field Coordinator for Trout Unlimited. “Given the toxic history of uranium mining in this region, we commend the leadership of this administration for enacting the wishes of millions of people hoping to preserve the beauty of this idyllic landscape.”

Three Unique Areas Contribute to New Monument

The three areas included within the new monument are located close to many other national monuments, national parks and national forests in northern Arizona and southern Utah. Yet they are unique.

The sweeping plateaus to the south, northeast, and northwest of Grand Canyon National Park constitute the three protected areas, each an integral part of the broader Grand Canyon ecosystem.

The northwestern area begins at the western edge of the Kanab watershed and northern boundary of Grand Canyon National Park and stretches north to the Shinarump Cliffs and Moonshine Ridge.

The northeastern area primarily includes parts of House Rock Valley and extends west from Marble Canyon along the Colorado River to the edge of the Kaibab Plateau.

The southern area includes a portion of the Coconino Plateau to the south of Grand Canyon National Park and extends from the border of the Havasupai Indian Reservation in the west to the Navajo Nation in the east.

These three areas to the south, northeast, and northwest of Grand Canyon National Park contain over 3,000 known cultural and historic sites, including 12 properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and possibly more in areas not yet surveyed.

The proclamation does not specify the locations of all treasures in the three newly protected areas. Some of the objects in these areas are sacred to Tribal Nations; are sensitive, rare, or vulnerable to vandalism and theft; or are unsafe to visit. Therefore, revealing their specific names or locations could pose a danger to the objects or to the public.

The surrounding plateaus, canyons, and tributaries of the Colorado River are central and sacred components of the origin and history of multiple Tribal Nations.

Many tribes recall that their ancestors are buried here and refer to these areas as their eternal home, a place of healing, and a source of spiritual sustenance. Like their ancestors, Indigenous peoples continue to use these areas for religious ceremonies; hunting; and gathering of plants, medicines, and other materials, including some found nowhere else on Earth.

More than 50 species of plants that grow in these areas, including catsclaw, willow, soapweed, and piñon, that have been identified as important to Tribal Nations. Historic shared use by different Tribes of the plateaus in the three areas, including for farming, hunting, and resource gathering on the Coconino Plateau, helped build strong, intergenerational relationships among the Tribal Nations that call this region home.

For hundreds of years, Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples used trails across portions of all three distinct landscapes to access sacred or important sites in surrounding areas such as the Grand Canyon, Mount Trumbull, and the Hopi salt mine. Routes throughout the southern area connect the Grand Canyon with the Paiute, Hopi, and Navajo homelands. Historically significant pathways in all three areas can still be seen on the landscape, and some continue to be actively used.

In the northwestern area, within the larger Kanab Creek drainage and particularly along Kanab Creek, there is evidence of ancient villages and habitations, including cliff houses, storage sites, granaries, pictographs, and pottery. The Kanab Plateau contains dwelling sites, including one known to have been occupied nearly 1,000 years ago, showing agricultural use and hunting by early inhabitants. The Kaibab Band of Paiute farmed in the area, which served as an important trade and transportation route, resource procurement and hunting area, and refuge during Euro-American encroachment into traditional territories.

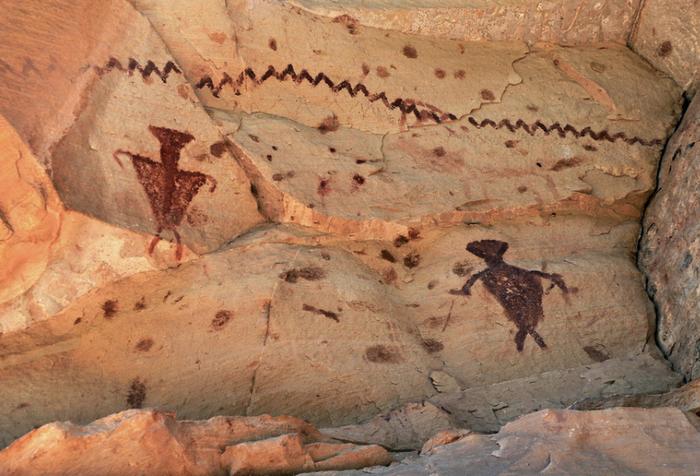

The pictographs and petroglyphs found in the Kanab Creek drainage present a spectacular collection of rock art. One pictograph and petroglyph site in Kanab Creek Canyon has been used for over 2,000 years, including for Ghost Dance ceremonies in the 19th century.

Also in the northwest, the BLM manages the Moonshine Spring and its associated historic cultural sites as the Moonshine Ridge Area of Critical Environmental Concern. Nearby Antelope Spring, Shinarump Cliffs, and Yellowstone Spring house historically important cultural sites, and the northwestern portion of the area is a historically significant resource and hunting area for the Southern Paiute.

In House Rock Valley in the northeastern area, many remnants of homes, storage buildings, pottery, and tools illustrate the area’s rich and extensive human history. The area has long been historically important to Tribal Nations for hunting and resource gathering, including to the Kaibab Band of Paiute for hunting deer and pronghorn and gathering piñon nuts, and to the San Juan Paiute for seasonal seed collection.

In the southern area, visible for miles in all directions, rises Red Butte, a towering landmark that is eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places as a traditional cultural property.

There are many other physical remnants of human habitation in the southern area, including lithic sites containing stone tools that may be more than 10,000 years old and more recent sites containing finely decorated pottery sherds that are between 800 and 1,100 years old.

Across the southern area, there is evidence of tool production using local materials and the historic use of fire for land management. Rock paintings, cave shelters, shrines, pit houses, masonry structures, and sites for religious ceremonies can be found throughout.

The southern area also provides opportunities for research about ancient occupation, including a long-term archaeological study area in the upper basin of the Coconino Plateau where research has been conducted for decades. This study area has led to research on the sourcing of materials for pottery, the conditions that influenced where people lived and congregated, the history and use of human-made fire, methods for recording archaeological sites, methods for protecting cultural resources, and human modification of bedrock.

Research has occurred in the area on the relationship between historic climate change and human occupation, including how climate changes affected construction techniques by the Indigenous peoples in the region, the viability of farming, the use of fire, and available resources.

Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians,” says creation of the monument is important. “President Biden’s designation of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument is a profound recognition of the historical and contemporary significance of these lands. This monumental decision honors our integral role in the conservation process, amplifies Native voices, and protects these sacred homelands for generations yet to experience them.”

Featured image: Kanab Creek Wilderness, one of the major tributaries of the Colorado River, contains a vast network of vertical walled gorges. Elevations within this wilderness range from 2,000 feet at the creek to 6,000 feet at the canyon rims. October 17, 2012 (Photo by Patrick Lair courtesy U.S. Forest Service, Southwestern Region, Kaibab National Forest)