WASHINGTON, DC, October 7, 2022 (ENS) – Today, the Biden Administration released a new 10-year National Strategy for the Arctic Region, which is melting at least three times faster than anywhere else on Earth. The new strategy addresses climate change with greater urgency and makes new investments in sustainable development to improve livelihoods for Arctic residents, while conserving the environment.

The northernmost region of Earth, the Arctic is the area within the Arctic Circle, a line of latitude about 66.5° north of the Equator. The new U.S. strategy updates the one issued under President Barack Obama in 2013.

“The Arctic – home to more than four million people, extensive natural resources, and unique ecosystems – is undergoing a dramatic transformation. Driven by climate change, this transformation will challenge livelihoods in the Arctic while at the same time creating new economic opportunities,” the White House recognized in a statement today.

One of the eight Arctic nations, the United States seeks an Arctic region that is “peaceful, stable, prosperous, and cooperative,” the administration said.

The new strategy accounts for “increasing strategic competition in the Arctic,” the White House said, “exacerbated by Russia’s unprovoked war in Ukraine and the People’s Republic of China’s increased efforts to garner influence in the region.” It seeks “to position the United States to both effectively compete and manage tensions.”

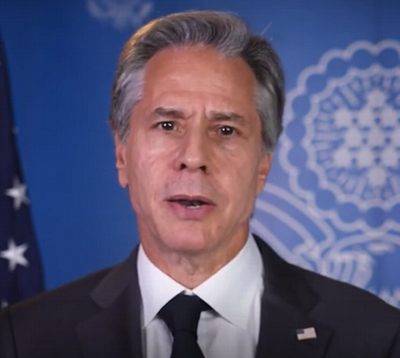

Secretary of State Antony Blinken today explained that the administration will advance U.S. interests in the Arctic “across four mutually reinforcing pillars spanning both domestic and international issues.”

Pillar 1 – Security: We will deter threats to the U.S. homeland and our allies by enhancing the capabilities required to defend our interests in the Arctic, while coordinating shared approaches to security with allies and partners and mitigating risks of unintended escalation.

“We will exercise U.S. government presence in the Arctic region as required to protect the American people and defend our sovereign territory,” the strategy states.

Pillar 2 – Climate Change and Environmental Protection: The U.S. government will partner with Alaskan communities and the State of Alaska to build resilience to the impacts of climate change, while working to reduce emissions from the Arctic as part of broader global mitigation efforts, improve scientific understanding, and conserve Arctic ecosystems.

Pillar 3 – Sustainable Economic Development: We will pursue sustainable development and improve livelihoods in Alaska, including for Alaska Native communities, by investing in infrastructure, improving access to services, and supporting growing economic sectors. We will also work with allies and partners to expand high-standard investment and sustainable development across the Arctic region.

Pillar 4 – International Cooperation and Governance: Despite the challenges to Arctic cooperation resulting from Russia’s war in Ukraine, the United States will work to sustain institutions for Arctic cooperation, including the Arctic Council, and position these institutions to manage the impacts of increasing activity in the region. We also seek to uphold international law, rules, norms, and standards in the Arctic.

This strategy is intended to serve as a framework to guide the U.S. government’s approach to tackling emerging challenges and opportunities in the Arctic. Our work will be guided by five principles that will be applied across all four pillars.

Consult, Coordinate, and Co-Manage with Alaska Native Tribes and Communities: The United States is committed to regular, meaningful, and robust consultation, coordination, and co-management with Alaska Native Tribes, communities, corporations, and other organizations and to equitable inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge.

Deepen Relationships with Allies and Partners: We will deepen our cooperation with Arctic Allies and partners: Canada, Kingdom of Denmark (including Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We will also expand Arctic cooperation with other countries that uphold international law, rules, norms, and standards in the region.

Plan for Long Lead-Time Investments: Many of the investments prioritized in this strategy will require long lead times. We will be proactive, anticipating changes coming to the Arctic over the next several decades and making new investments now to be prepared.

Cultivate Cross-Sectoral Coalitions and Innovative Ideas: The challenges and opportunities in the Arctic cannot be solved by national governments alone. The United States will strengthen and build on coalitions of private sector; academia; civil society; and state, local, and Tribal actors to encourage and harness innovative ideas to tackle these challenges.

Commit to a Whole of Government, Evidence-Based Approach: The Arctic region extends beyond the responsibility of any single region or government agency. U.S. federal departments and agencies will work together to realize this strategy. We will deploy evidence-based decision-making and carry out our work in close partnership with the State of Alaska; Alaska Native Tribes, communities, corporations, and other organizations; and local communities.

Alaska’s Arctic Advantages

The most northerly U.S. state, Alaska, is planning to turn the global energy crunch brought on by Russia’s war in Ukraine, into an opportunity.

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy September 30 signed an Administrative Order creating the Office of Energy Innovation to address the evolving energy needs of Alaska, and with recognition of the positive economic impacts that come from domestic energy production.

The Office of Energy Innovation, operating within the Office of the Governor, will develop policies that enhance Alaska’s role in a national clean energy future through the development of a strong and responsible critical minerals mining program and the investment in emerging energy technologies.

“Alaska is an energy giant in all its forms. We’ll continue to be an oil and gas giant, but we are all in for every form of energy – wind, solar, hydro, tidal, geothermal, micronuclear, and hydrogen. The Office of Energy Innovation will coordinate this pursuit of sustainable, dependable, and affordable energy,” said Governor Dunleavy.

“From AEA’s electric vehicle charging station plan to the U.S. Air Force this week releasing a RFP [Request for Proposals] for the Eielson Air Force Base micro-reactor pilot program, Alaska has seen a number of exciting developments recently,” the governor said.

Microreactors are compact nuclear reactors that will be small enough to transport by road, rail or air and could help solve energy challenges. The Eielson micro-reactor will be licensed by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, but commercially owned and operated.

“Energy is a critical asset to ensure mission continuity at our installations,” said Mark Correll, the deputy assistant secretary of the Air Force for Environment, Safety and Infrastructure in a statement announcing the project. Correll will coordinate the project with the Air Force Office of Energy Assurance, the office of the deputy assistant secretary of Defense for Environment and Energy Resilience, the Department of Energy, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Who Governs the Arctic? What the Arctic Council Does & What It Cannot Do

The 1996 Ottawa Declaration established the Arctic Council as the high-level intergovernmental forum for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states, with the direct involvement of the Arctic Indigenous communities and other Arctic inhabitants, on issues such as sustainable development and environmental protection.

The Arctic Council’s mandate, as articulated in the Ottawa Declaration, explicitly excludes military security.

At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle, and these are the member states of the council: Canada; Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Norway; Russia; Sweden; and the United States.

All Arctic Council decisions and statements require consensus of all eight Arctic States.

Other countries or national groups can be admitted to the Arctic Council as observers, while organizations representing the concerns of indigenous peoples can be admitted as indigenous permanent participants. Right now, in addition to the eight Arctic States, the Council includes six Indigenous Permanent Participant organizations, six Working Groups and 38 Observer states and organizations.

Based in Tromso, Norway, the Arctic Council is a forum; it has no programming budget. All projects or initiatives are sponsored by one or more Arctic States. Some projects also receive support from other entities.

The Arctic Council does not and cannot implement or enforce its guidelines, assessments or recommendations. That responsibility belongs to individual Arctic States or international bodies.

The Arctic Council has conducted studies on climate change, oil and gas, and Arctic shipping. And, the Council was used as a forum for the negotiation of three legally binding agreements among the eight Arctic States:

- – Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic (2011)

- – Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (2013)

- – Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation (2017)

The Chairmanship of the Arctic Council rotates every two years among the eight Arctic States.

The Russian Federation assumed the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council in May 2021 and will chair the intergovernmental forum until spring 2023.

The Russian Chairmanship program outlined four priority areas for its two-year term: Arctic inhabitants and Indigenous peoples, environmental protection and climate change, socioeconomic development, and strengthening the Arctic Council.

More about the Russian Chairmanship priorities here: https://arctic-council.org/about/russian-chairmanship-2/. The operator of events under the Russian Chairmanship of the Arctic Council 2021-2023 is the Roscongress Foundation: https://roscongress.org/en/

Even so, not quite a year after Russia assumed the Chairmanship of the Council, Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

A week later, on March 3, the other Arctic Council founding states: Canada, Finland, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the United States, refused to cooperate with Russia.

Announcing a pause in their participation in the Arctic Council, the seven withdrawing countries said their action was, “In response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a flagrant violation of the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity, based on international law.”

About three months later, in June, the seven countries picked up their Arctic Council work, but only they still would not work with Russia. “We remain convinced of the enduring value of the Arctic Council for circumpolar cooperation and reiterate our support for this forum and its important work,” they said.

“We intend to implement a limited resumption of our work in the Arctic Council, in projects that do not involve the participation of the Russian Federation. These projects, contained in the workplan approved by all eight Arctic States at the Reykjavik ministerial, are a vital component of our responsibility to the people of the Arctic, including Indigenous Peoples.”

Arctic Council Secretariat Changes Hands

For about a week, just since the end of September, Mathieu Parker has held the position of Director of the Arctic Council Secretariat, ACS.

A Canadian, Parker comes to his new role from a job as Vice-President of Pan-Territorial Operations for the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency.

Parker lived and worked in Iqualuit, in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut. With 7,740 residents, Iqaluit is the capital, largest, and only city in Nunavut. It lies on vast Baffin Island in Frobisher Bay, known for its ice-capped mountains and tundra valleys.

The former Canadian government executive takes over the role from Norwegian national Nina Buvang Vaaja, who ended her term as ACS Director in August 2021 after serving the Arctic Council for 12 years.

On September 19, 2022 just before she left ACS, Vaaja tweeted, “Today it is 25 years since the Ottawa Declaration was signed. Through cooperation, dialogue and trust the Council has contributed to increased knowledge, peace and stability in the #Arctic – Thank you!”

Vaaja now moves to Barents Watch, a 10-year-old Norwegian initiative presenting information about the seas and coastal areas from the south of Sweden, to Greenland to the North Pole.

There is plenty to watch.

Scientists Investigate Arctic Change

The Arctic is warming three times as fast and the global average, according to the Norwegian Polar Institute, NPI. The melting of snow and ice exposes a darker surface and increases the amount of solar energy absorbed in these areas, and this regional warming leads to continued loss of sea ice, melting of glaciers and of the Greenland ice cap, the Institute explains.

With the loss of sea ice, the Arctic Ocean will be more accessible to human activities, and scientists are at work right now to learn what they need to manage these changes as best they can.

Along mooring lines attached to the sea floor, scientists have attached scientific instruments to collect data from different depths of the water column, to capture the year-round characteristics of the sea ice drifting by at the surface, the water properties and circulation, and the species composition of the ecosystem. All components needed to understand the rapid changes of the Arctic Ocean.

Engineer Kristen Fossan who leads the mooring deployment operation, explained, “The mooring is held in position by a bottom anchor and is kept vertical by subsurface floats placed at regular intervals that lift the instruments and line.”

“The scientific moorings deployed during the NPI Arctic Ocean 2022 cruise are the beginning of a long time series that is crucial for the best possible management of this region,” says chief scientist Paul Dodd.

Dodd leads the Fram Centre https://framsenteret.no/english/ programme SUDARCO, which stands for Sustainable Development of the Arctic Ocean. The Fram Centre is formally known as the High North Research Centre for Climate and the Environment, 69 researchers and technicians from nine Fram Centre member institutions are participating.

“They will provide a comprehensive set of continuous measurements at two key locations, for an initial period of two years. Collecting year-round in-situ observations from fixed locations in this environment is unique and the instruments deployed during the Arctic Ocean 2022 cruise lay the foundation for an exciting new research program,” Dodd explained.

The Arctic expedition and the rigs are financed by Norway’s Ministry of Climate and Environment and Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“We expect an increase in ship traffic in the Arctic Ocean, including tourism, new shipping routes and perhaps eventually fishing activity,” Dodd projected. “To manage the region in the best possible way, we need to map what is valuable and vulnerable. The mooring observations are needed to understand newly accessible parts of the marine environment and the ecosystem.”

The melting of polar ice is not only shifting the levels of our oceans, it is changing the planet Earth itself, according to scientists at Harvard University. Ph.D. Sophie Coulson and her colleagues explained in a September 2021 paper in “Geophysical Research Letters” that, as glacial ice from Greenland, Antarctica, and the Arctic Islands melts, Earth’s crust beneath these land masses warps, an impact that can be measured hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

“Scientists have done a lot of work directly beneath ice sheets and glaciers,” said Coulson. “So they knew that it would define the region where the glaciers are, but they hadn’t realized that it was global in scale.”

Another group of scientists is exploring the Arctic Beringia region.

At the meeting of the eastern and western hemispheres, the Arctic Beringia encompasses an area of tundra and productive shallow marine shelf areas that extend from the Kolyma River in the Chukotka region of the Russian Federation, across northern Alaska in the United States, and as far east as Victoria Island in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of Canada.

This region hosts vast intact tundra landscapes and seascapes with robust assemblages of free-ranging native species such as walrus and caribou, supports vibrant mixed economies for indigenous communities, and is valued by diverse stakeholders across the globe.

The Wildlife Conservation Society, WCS, based at New York’s Brox Zoo, is working with Arctic communities in the Arctic Beringia to secure the long-term needs of wildlife through partnerships, including with industry and local peoples facing a growing development footprint and profound climate change impacts.

Their goals are

- – Strengthening a network of protected areas

- – Promoting well managed public and indigenous lands and waters

- – Fostering strong management roles for indigenous communities

“We use the best available science and indigenous knowledge, along with expertise in trans-boundary policy, to work with diverse communities, indigenous groups, agencies and other partners to understand and protect wild places and wildlife, including their role in local food security,” the WCS says.

WCS uses science to ensure no loss of protections for protected areas, including Wrangel Island World Heritage Area, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and Anguniaqvia niqiqyuam Marine Protected Area, as well as implementation of new protected areas such as the recent 32,500 square kilometers of Marine Protected Area in the Bering Sea.

WCS has Arctic protection programs underway in both Canada and Russia.

The Canadian program combines insights gained from “muddy boots” fieldwork with a “big-picture conservation vision” to speak up for species such as caribou, wolverine, bats, bison, freshwater fish and marine mammals. WCS Canada’s unique approach has led to conservation successes, including a seven-fold expansion of Nahanni National Park, protection of Yukon’s pristine Peel Watershed and the creation of the Castle Wildland Park in southern Alberta.

The WCS’ Russian program works to protect the extensive forest and tundra ecosystems of the Russian Far East and the many species whose survival depends on these intact, functional ecosystems. WCS Russia uses science as a foundation for conservation actions to keep Amur tigers, Far Eastern leopards, Kamchatka brown bears, and Blakiston’s fish owls alive, along with many vulnerable other species.

Climate Conference COP27 to Consider the Arctic

In less than a month, the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, known as COP27, will take place in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt from November 6 to 18, 2022. Arctic issues will be front and center.

The International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, ICCI, based in the United States and the European Union, is organizing the COP27 Cryosphere Pavilion, which will focus on side events – six, 90-minute slots each day, including ministerial-level speeches and strong Youth and Indigenous participation.

- – Implementation to Avert Overshoot: Pathways to Emissions Reductions. This day will focus on those pathways or implementation efforts that present feasible options to prevent global impacts from cryosphere, with a narrowing window for action.

- – Mountains: Glaciers and Snow: Centuries of Impacts on Water Resources. Mid-latitude glaciers suffer nearly total loss at overshoot above 2°C, but may preserve some basis for re-growth and restoration of water and other ecosystem services at 1.5°C. However, mountain-dependent regions will face many centuries or thousands of years for restoration. Two days will focus exclusively on the Hindu Kush Himalaya region, on which at least 2.5 billion people depend for water-related needs and ecosystem services.

- – Polar Oceans: Long-tailed Legacy of Acidification, Warming and Freshening. Polar oceans and high latitude seas already show fisheries and shell impacts today because these colder waters absorb CO2 more quickly. Those impacts will be greater still with overshoot of CO2 concentrations above 450ppm. Warming, freshening and invasion by low latitude species all only add stress towards (in worst-case emissions) a mass extinction event.

- – Ice Sheets: Overshoot Thresholds for Irreversible Sea-level Rise. The WAIS and its collapse will causes 4-6m of sea-level rise over time, and may already have passed that point even today; but chances of slowing or preventing that collapse are far better without overshoot of 1.5°C. In Earth’s past, even 2°C has resulted in 12-20 meters of sea-level rise, potentially triggered by overshoot and that may not be reversible with later Paris implementation.

- – Permafrost: Centuries of Carbon Emissions from Overshoot. Permafrost carbon emissions drive some degree of global warming. Those emissions are increasing: they are already on the order of Japan’s. Overshoot to 3-4°C will introduce a “permafrost contribution” closer to that of China or the U.S. today, lasting 100-200 years and necessitating generations of negative emissions well after anthropogenic emissions cease.

- – Absent Arctic Summer Sea Ice: Global Feedbacks. Ice-free summers will still occur within the 1.5°C limit; but with even slight overshoot to 1.7°C, this is projected to become an annual phenomenon. Increasing ice-free summer conditions will cause global feedbacks, including increased permafrost thaw, rising Greenland ice loss and sea-level rise; and damage to Arctic food chains dependent on thick, multi-year ice.

The Cryosphere Pavilion will host nightly cultural events, pairing for example cryosphere and low-lying nations; and providing an opportunity for both virtual viewing and accredited participants to mingle and find some respite from the negotiations.

Please use the application process outlined here to organize a cultural event – whether art, music or beyond – to explore the connections between the creative community and cryosphere and/or climate change.

In another pavilion at COP27, a group of the world’s top ocean science and philanthropic organizations, led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, WHOI, and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, will highlight the global ocean.

The Ocean Pavilion in the conference’s official meeting area will highlight the critical importance of the ocean to Earth’s climate and to efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change in the safest, most effective ways science can offer.

It will be the first time the ocean has been the singular focus of a pavilion inside the central Blue Zone at any COP and the first time a pavilion has been organized mainly by a group of research institutions.

“Earth is an ocean planet,” said WHOI President and Director Peter de Menocal. “The ocean gives us the oxygen we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat. It also provides jobs for billions of people, including many of the world’s most vulnerable. It’s only natural that the ocean should also be at the center of discussions about the sustainability of human activity on Earth, including how it can help stabilize the global climate system at a safe level.”

“The ocean is the engine of Earth’s climate,” said Margaret Leinen, director of Scripps Oceanography, and vice chancellor for Marine Sciences at UC San Diego. “We know that it has absorbed 90 percent of the heat produced by human activity since the dawn of the industrial age and it holds 20 times more carbon than the atmosphere and terrestrial plants combined. Put simply, the ocean is climate, and the climate is the ocean.”

The Ocean Pavilion will serve as a central hub for conference delegates to exchange ideas about how to address climate change by leveraging the ocean.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries pledged to collectively cut their greenhouse gas emissions enough to keep the planet from warming by no more than 1.5 to 2°C (2.7 to 3.6°F) relative to pre-industrial times.

Progress toward those goals has lagged and, as a result, the planet has already warmed by about 1°C, lending greater urgency to the search for safe, effective solutions to reduce the upward march of global temperatures.

Featured image: Arctic ice floats offshore of the U.S. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, July 7, 2019 (Photo by Danielle Brigida, US Fish & Wildlife Service)