WASHINGTON, DC, February 3, 2023 (ENS) – They’re called “forever chemicals” for a reason – because they don’t break down in the environment over time. Toxic per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, are the forever chemicals, and they’re not rare – more than 9,000 PFAS have been identified.

These chemicals, resistant to both water and grease, are used in products from nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing, take-out containers and food packaging, to firefighting foams, fire retardants and repellents. And these compounds now are found in drinking water systems across the United States.

Scientists from the nonprofit Environmental Working Group, David Andrews and his EWG colleague Olga Naidenko, estimated in 2021 that the tap water of more than 200 million people, a majority of Americans, is contaminated with a mixture of PFOA and PFOS at concentrations of one part per trillion (ppt) or higher.

Last October, another nonprofit, the Waterkeeper Alliance, released its analysis of American waterways. It, too, sounds a loud alarm. In a test of 114 waterways across the country, 83 percent were found to contain at least one type of PFAS.

(Photo by Sergei Gussev)

San Diego Creek in Orange County, California contained the highest levels of PFAS concentrations of all sample sites on the West Coast. In total, 15 different PFAS compounds were found in detectable quantities.

But exposure to these chemicals harms both the environment and health health. Human exposure to PFAS is linked to kidney and testicular cancer, impaired functioning of the liver, kidneys, and immune system, endocrine disruption, fertility problems, birth defects, and developmental damage to infants, according to the National Institutes of Health. The agency points to a long-term study showing a link between PFAS exposure and increased risk of Type 2 diabetes in women. Other studies indicate a decrease in vaccine effectiveness in children.

When he was campaigning for the 2020 election, now President Joe Biden issued an environmental justice plan that called out forever chemicals. The plan promised that if elected Biden would “tackle PFAS pollution by designating PFAS as a hazardous substance, setting enforceable limits for PFAS in the Safe Drinking Water Act, prioritizing substitutes through procurement, and accelerating toxicity studies and research on PFAS.”

In October 2021, the Biden Administration’s Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, launched a new three-year PFAS Roadmap to guide the agency’s activities to research, restrict, and remediate harmful PFAS through 2024.

The PFAS Roadmap includes a new national testing strategy to accelerate research and regulatory development, a proposal to designate certain PFAS as hazardous substances under an existing law, and actions to broaden and accelerate the cleanup of PFAS as well as steps to, “hold polluters accountable [and] address the impacts on disadvantaged communities,” according to a White House fact sheet. The roadmap is the product of the EPA PFAS Council, which EPA Administrator Michael Regan established soon after he took office.

The alarm bells keep ringing. Last June, the Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, released updated health advisories warning that even tiny amounts of two types of the chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, are harmful to human health.

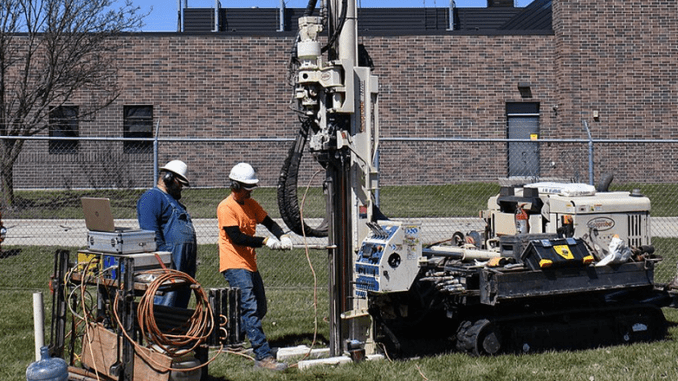

On the cleanup front, the Department of Defense is moving swiftly to address PFAS at military sites throughout the country, but it’s a big job and progress is slow. The department is currently conducting PFAS cleanup assessments at the nearly 700 DOD installations and National Guard locations where PFAS was used or may have been released, and expects to have completed all initial assessments by the end of 2023.

Last week, the EPA took another step to limit the amount of PFAS chemicals are released into the environment by seeking public comment on limiting “inactive” PFAS.

EPA Proposal Would Check Out “Inactive” PFAS

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has just proposed for public comment a rule that would prevent companies from starting or resuming the manufacture, processing or use of an estimated 300 PFAS that have not been made or used for many years without a complete EPA review and risk determination.

In the past, these chemicals, known as “inactive PFAS,” may have been used as binding agents, surfactants, in the production of sealants and gaskets, and may have been released into the environment, the EPA says.

An “inactive” designation means that a chemical substance has not been manufactured (including imported) or processed in the United States since June 21, 2006. Without the proposed rule, companies could resume uses of these PFAS without notification to and review by EPA.

“This proposal is part of EPA’s comprehensive strategy to stop PFAS from entering our air, land and water and harming our health and the planet,” said Assistant Administrator for the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention Michal Freedhoff, who helped to reform the Toxic Substances Control Act in 2016.

“The rule would put needed protections in place where none currently exist to ensure that EPA can slam the door shut on all unsafe uses of these 300 PFAS,” she said.

When the Toxic Substances Control Act, TSCA, was first passed in 1976, thousands of chemicals were grandfathered in under the statute and allowed to remain in commerce without additional EPA review.

Before TSCA was amended in 2016, EPA completed formal reviews on only about 20 percent of new chemicals and had no authority to address new chemicals about which the agency lacked sufficient information. This is part of the reason why many chemicals, including PFAS, were allowed into commerce without a complete review, Freedhoff explained in a statement.

Under the newly proposed Significant New Use Rule, if the EPA adopts it after public comment, the agency must formally review the safety of all of new chemicals before they are allowed into commerce.

TSCA also requires EPA to compile, keep current and publish a list of each chemical that is manufactured, imported, or processed in the United States for uses under TSCA, known as the TSCA Inventory. TSCA also requires EPA to designate each chemical on the TSCA Inventory as either “active” or “inactive” in commerce.

The proposal would first require companies to notify EPA before they could use any of these 300 chemicals. The agency would then be required to conduct a robust review of health and safety information under the modernized 2016 law to determine if their use may present unreasonable risk to human health or the environment and put any necessary restrictions in place before the use could restart.

EPA will accept public comments on the proposed rule for 60 days following publication in the Federal Register via docket EPA-HQ-OPPT-2022-0876 at www.regulations.gov

Meanwhile, There’s a Tool for That

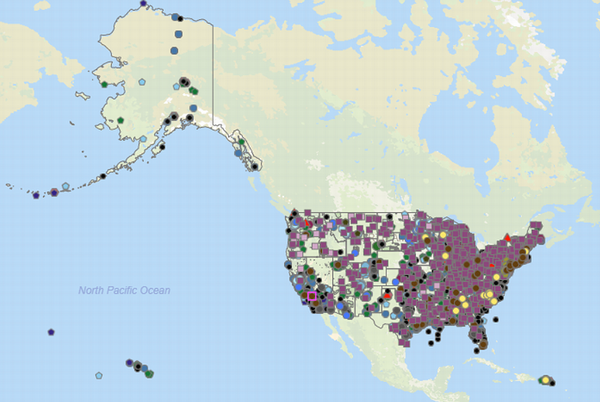

On January 5, the EPA offered something new for people concerned about PFAS and the harms they can cause.

EPA released a new interactive webpage, called the “PFAS Analytic Tools,” which provides comprehensive information about per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances across the country.

EPA’s PFAS Analytic Tools draws from multiple national databases and reports to consolidate information in one webpage.

The tools allow mapping, charting, and filtering functions, so the public can see where testing has been done and what level of PFAS detections were measured.

“EPA’s PFAS Analytic Tools webpage brings together for the first time data from multiple sources in an easy to use format,” said John Dombrowski, director of EPA’s Office of Compliance. “This webpage will help communities gain a better understanding of local PFAS sources.”

The PFAS Analytic Tools includes information on Clean Water Act PFAS discharges from permitted sources, reported spills containing PFAS constituents, facilities historically manufacturing or importing PFAS, federally owned locations where PFAS is being investigated, transfers of PFAS-containing waste, PFAS detection in natural resources such as fish or surface water, and drinking water testing results.

The tools cover a broad list of PFAS and represent EPA’s ongoing efforts to provide the public with access to the growing amount of testing information that is available.

Because the regulatory framework for PFAS chemicals is emerging, data users should pay close attention to the caveats found within the site, the EPA advises.

Rather than wait for complete national data to be available, EPA is publishing what is currently available while information continues to fill in. Because of the differences in testing and reporting across the country, EPA officials warn that the data “should not be used for comparisons across cities, counties, or states.”

To improve the availability of the data in the future, EPA has published its fifth Safe Drinking Water Act Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule to expand on the initial drinking water data reporting that was conducted in 2013-2016.

Beginning in 2023, this expansion will bring the number of drinking water PFAS samples collected by regulatory agencies into the millions, the agency says.

EPA also expanded the Toxics Release Inventory reporting requirements in recent years to include over 175 PFAS substances, and more information should be received in 2023.

EPA will continue working toward the expansion of data sets in the PFAS Analytic Tools to improve collective knowledge about PFAS occurrence in the environment.

See information about the new PFAS Analytic Tools here and open the tools here.

PFAS Fighters Make Progress on the Scientific Front

The National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program funds the search for practical applications to protect the public from exposures to hazardous substances.

Examples include:

- The Sources, Transport, Exposure, and Effects of PFASs (STEEP) project, at the University of Rhode Island, is identifying sources of PFAS contamination, assessing human health effects, and educating communities on ways to reduce exposure. 11

- The Michigan State Superfund Research Center is developing energy-efficient nanoreactors capable of breaking the carbon-fluorine bond that keeps PFAS from degrading.

- Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, are working on options to contain aqueous film-forming foams used for firefighting, a major source of PFAS contamination.

- The Brown University Superfund Research Center has developed databases that exploit land use data to identify cities and towns at high risk for PFAS exposure. 12

- Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grantee CycloPure, Inc., has developed a new way to remove hazardous PFAS from water. The water pitcher-based filters should be an affordable option for people concerned about PFAS exposure where they live or work.

- A team at the North Carolina State University SRP Center is studying alligators living in PFAS-contaminated water to understand possible effects on the immune system. They also developed a new high-throughput tool to quickly characterize how PFAS may be transported within the body and potentially cause harm.

- Another SBIR project by EnChem Engineering, Inc. is developing an innovative technology to speed up removal of PFAS at Superfund sites.

- SRP-funded small business AxNano developed a portable tool that relies on nanoparticles to quickly detect PFAS in samples. Their method is more affordable and efficient than traditional mass spectrometry.

Featured image: Drillers with Plains Environmental Services, Inc. conduct hydraulic profiling and electrical conductivity testing using a Geoprobe mobile drilling rig during a remedial investigation into the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, at Truax Field in Madison, Wisconsin, March 22, 2022. (Photo by Senior Master Sgt. Paul Gorman courtesy U.S. Air National Guard)