NEW YORK, New York, September 22, 2023 (ENS) – The hard-won High Seas Treaty, the first agreement to protect the two-thirds of the world’s oceans beyond national jurisdiction, was opened for signature by United Nations Member States on September 20 at UN Headquarters in New York. Signing up enthusiastically, 80 countries and the European Union indicated their support for safeguarding the open oceans. To take effect, the treaty must be ratified or approved by 60 national governments.

“The ocean is one global system, and its health is key to the health of our planet, Antony Blinken, U.S. Secretary of State, said. “This historic High Seas Treaty creates a coordinated approach to establishing marine protected areas on the high seas, a critical step to conserving ocean biodiversity and reaching the global community’s “30×30” target to conserve or protect at least 30 percent of the ocean by 2030.”

“The United States stands with the global community in committing to safeguard the health and resilience of our ocean so that it may continue to sustain us for generations to come,” Blinken declared.

The High Seas Treaty will allow the establishment of marine protected areas in the high seas at global level, safeguarding the ocean from human pressures in a major contribution to reducing climate change, to protecting biodiversity and achieving the objective to protect at least 30% of the planet by 2030.

The treaty also sets a framework for a fair and equitable sharing of monetary and non-monetary benefits from marine genetic resources. It enables capacity building and transfer of marine technologies to developing countries, as well as a voluntary fund to support developing countries to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Below Water.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on behalf of the EU, inviting other countries to do the same, and many of the other EU countries also signed, including: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

“It is a historic day for the protection of the High Seas!” rejoiced EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries Virginijus Sinkevičius of Lithuania. “But we need to keep working towards a swift ratification, with the hope that the treaty can enter into force by the June 2025 UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France,” he said.

The High Seas Treaty shall remain open for signature until September 20, 2025.

For a full text of the High Seas Treaty and a list of signatory governments, click here.

The open oceans cover about 70 percent of the planet and support every function of life on Earth. Yet fragmented legal frameworks have left marine life on the high seas vulnerable to the menaces of climate change, plastic pollution, oil spills, overfishing, habitat destruction, acidification, and underwater noise. Only about 1% of the high seas is currently protected.

After difficult negotiations that have lasted 20 years, delegates to the United Nations from 193 governments agreed in principle back in March to protect marine biodiversity on the high seas. Then, after a technical edit and translation into all UN languages, on June 19 UN Member States formally approved the final text of the world’s first High Seas Treaty.

Delegates from the 193 member nations rose in a standing ovation when Singapore’s ambassador on ocean issues, Rena Lee, who led the negotiations, brought them to a successful conclusion after hearing no objections to the treaty’s approval.

Adopted by the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, BBNJ, the High Seas Treaty takes stewardship responsibility of the oceans on behalf of present and future generations, in line with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS, an overarching treaty that dates back to 1994.

The new agreement contains 75 articles that aim at protecting, caring for, and ensuring the responsible use of the marine environment, maintaining the integrity of ocean ecosystems, and conserving the inherent value of marine biological diversity on the high seas.

The treaty creates a new body to manage conservation of ocean life and establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in the high seas.

“The ocean is the lifeblood of our planet, and today, you have pumped new life and hope to give the ocean a fighting chance,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told delegates June 19 as they approved the final text of the High Seas Treaty.

“This action is a victory for multilateralism and for global efforts to counter the destructive trends facing ocean health, now and for generations to come. It is crucial for addressing the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution,” Guterres said.

Today, only one percent of the high seas is governed by rules that restrict human activity in the interests of protecting biodiversity. The treaty newly empowers States to establish a network of Marine Protected Areas, or MPAs, to extend that protection.

It intended to encourage governments to deliver on their 30×30 pledge under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreed last year – to protect at least 30 percent of land, coastal areas and the ocean by 2030 “through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing indigenous and traditional territories.”

Conservation Groups Urge Swift Ratification

“The ocean cannot wait. It has taken nearly 20 years to adopt this treaty. Over that time period, industrial fishing has taken a heavy toll on the high seas, depleting wild fish populations and driving an alarming decline in oceanic shark populations,” said Jessica Battle, senior global ocean governance and policy expert with the global nonprofit WWF International. “Nations must now swiftly ratify this treaty and start identifying areas of the high seas for protection immediately.”

“The high seas are humanity’s greatest global commons, and they are a vital part of our planet’s life-support system. But only about one percent of the high seas is currently protected,” said Pepe Clarke, Oceans Practice Leader with WWF International.

“Last year, governments around the world committed to protecting and conserving 30 percent of the ocean by 2030, and the formal adoption of the High Seas Treaty is a key milestone on the path to achieving that vitally important global target,” Clarke said.

Today, just one percent of the high seas is governed by rules that limit human behavior to safeguard the diversity of life in this area of the oceans.

The High Seas Treaty offers signatories the authority to establish a network of Marine Protected Areas, MPAs, that will extend that protection. It can help governments to deliver on the ambitious ‘30×30’ commitment under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, to protect at least 30 percent of land, coastal areas and the ocean by the year 2030.

Chris Thorne of Greenpeace’s Protect the Oceans campaign said, “This treaty is a win for all life on this planet. Now those same governments which agreed it must urgently ratify and begin delivering vast ocean sanctuaries on the high seas. The science is clear, we must protect at least 30% of the oceans by 2030 to give the oceans a chance to recover and thrive.

“2030 looms large on the horizon, and the scale of our task is vast. Less than 1% of the high seas are protected. Millions of people from all over the world have demanded change and together we have achieved this historic agreement, but we still have a long way to go,” Thorne said.

“We are committed to achieving 30×30. We will work day and night to ensure this Treaty is ratified in 2025, and ocean sanctuaries free from destructive human activities covering 30% of the oceans become a reality by the end of this decade,” he said.

Since its founding in 2011, the High Seas Alliance with its 50+ nongovernmental members and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN, has been working towards protecting the High Seas – the global ocean beyond national jurisdiction. “This area includes some of the most biologically important, least protected, and most critically threatened ecosystems in the world,” the group says.

“I would like to warmly thank the High Seas Alliance for its restless work on the conclusion of the BBNJ Agreement. This is a historic achievement. The conclusion of the BBNJ Agreement was a priority of the European Union and its Member States. It is now a priority to ensure it swiftly enters into force and is effectively implemented,” said Virginijus Sinkevicius of Lithuania, the European Union’s Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries.

The High Seas Alliance is aiming for at least 60 countries to have ratified the High Seas Treaty by the time the UN Ocean Conference opens in France in June 2025.

Minna Epps, who heads the IUCN Ocean Programme, said right after the treaty’s text was finalized in June, “We have once again shown that we can deliver on the promise of multilateralism for protection of our planet. Global threats need global action. We now need to enact the enabling conditions for timely, effective, fair and equitable implementation. It has been a long journey, that many colleagues have been part of, and I would like to honour them all, especially the President Ambassador Rena Lee for her dedication, hard work and inclusiveness.”

Singapore’s Ambassador for Oceans and Law of the Sea Issues and Special Envoy of the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Lee specializes in the practice of law of the sea, as well as environmental and climate change law. In 2018, she was elected president of the UN Intergovernmental Conference that negotiated the High Seas Treaty.

IUCN Commissions have provided independent legal and scientific expertise throughout the decades-long processes of BBNJ Treaty negotiations and, through its members, IUCN has called for High Seas protection in resolutions as far back as 2000.

IUCN is particularly thankful to the States for enabling the participation of observers including civil society. As a result, IUCN was able to support the negotiations with scientific and legal advice through its multidisciplinary experts, including marine biologists, finance experts, and international lawyers knowledgeable in intellectual property, environmental, and treaty law.

IUCN now calls on all States to sign the High Seas Biodiversity Treaty this September at UN Headquarters in New York, and is urging at least 60 States to ratify it swiftly in order to bring it into force as soon as possible and no later than 2025.

“Early entry into force, preparations for the first Conference of the Parties (COP), national implementation, and the prompt establishment of its institutions will be key in achieving the objectives of the treaty,” said Cymie Payne, who chairs the IUCN Ocean Law Specialist Group of the World Commission of Environmental Law.

Director of The Pew Charitable Trust, Liz Karan, said, “High seas marine protected areas can play a critical role in the impacts of climate change. Governments and civil society must now ensure the agreement is adopted and rapidly enters into force and is effectively implemented to safeguard high seas biodiversity.”

‘Aggressive Non-violence:’ Captain Paul Watson’s Continuing Adventures

One high-profile supporter of the new treaty is Captain Paul Watson, the Canadian conservationist and author who has spent most of his adult life combating the slaughter of whales, seals and other marine mammals on the high seas.

“The 🌊 UN High Seas Treaty 🌊 aims to protect a part of the Ocean that has been vastly unregulated and exploited by commercial fishing for many years. It provides a glimmer of hope and is a step in the right direction in the fight to protect marine biodiversity,” he posted on Instagram.

“Like all treaties and agreements between governing bodies, it is vital that we implement effectively and enforce severely, otherwise they are just words on paper. With the Captain Paul Watson Foundation, “We will continue to block, harass, and make it impossible for these illegal commercial whalers and fisheries to ravage our Ocean!” he posted.

“We hope this long awaited treaty helps chart a new course for the future of our Ocean and our Planet, but we must be vigilant and steadfast in our commitment,” Watson said.

Watson, a Greenpeace co-founder who sailed against and foiled Russian whalers, left the organization and founded the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in 1977 in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

“I call what we do aggressive non-violence,” he says on Instagram. With open ocean campaigns against whalers and sealers, Watson built the Sea Shepherd into a global force for marine mammal conservation, but he was ejected from the SSCS about a year ago in an altercation over the future direction of the organization.

Now, to carry on his fight to safeguard marine life, Watson has partnered with IT expert Omar Todd. They have co-founded the U.S.-based nonprofit Captain Paul Watson Foundation, headquartered in New York City, which is not associated or affiliated with Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.

The new operational campaign name for the Captain Paul Watson Foundation is Neptune’s Pirates, Watson has announced.

An open letter to supporters issued August 28 gives the current state of his conservation work and his feelings about the split with his former organization.

“We have a new ship to continue the old mission, the mission that we were created for and we will complete that mission because of the incredible crew of loyal supporters, some of them new but most the same people that sailed under the same flag that was taken from us by a hostile mutiny of craven opportunists,” Watson wrote.

“What I now see is the freedom to move forward unencumbered by the bureaucrats and the naysayers, to once again risk all and to go where others refuse to go and to do what those ungrateful mutineers no longer have the courage or the imagination to do,” he wrote.

“Those who kill whales and slaughter dolphins know that it was not the name Sea Shepherd alone that established our reputation as the most effective anti-whaling movement on the planet,” Watson said in the letter.

“It was Sea Shepherd under my command that drove the pirate whalers from the Atlantic, that sank half the Icelandic fleet, half the Spanish fleet and four Norwegian whalers. It was Sea Shepherd under my command that invaded Soviet Siberia to document illegal whaling, and it was Sea Shepherd under my command that helped to take down the commercial market for Canadian seal products. It was Sea Shepherd under my command that drove the Japanese whaling fleet out of the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary,” wrote Watson.

“Already our reputation has gone before us,” he wrote. “All we did in June of this year was to arrive in Icelandic waters and within hours of our arrival, the killing of endangered fin whales was shut down for the summer…”

Commercial fin whaling in Iceland is being allowed during September – but with stricter conditions, including monitoring. Kristján Loftsson, owner of Hvalur hf., the last whaling operation in Iceland, installed copper electric harpoon wires on his ships in June, Watson reported. But in Iceland the use of electricity on whales is not authorized for September, he said.

“All we had to do was set a course towards the Faroe Islands and immediately the Faorese issued a restriction against us entering their territory, a restriction we ignored twice in order to intervene against the slaughter of pilot whales,” Watson revealed.

“Omar Todd has the helm of the Foundation, and the Foundation and all its supporters have given me command of the ships and campaigns,” he wrote.

Still sore about the split with the organization he built and operated for more than 40 years, Captain Watson maintains his identity as a pirate for the oceans, saying in the letter, “Pirate ships and pirate campaigns need a genuine pirate to set the course and to lead the crew into battle. I have the credentials.”

“In 2014, Judge Alex Kozinski of the 9th Circuit Federal Court of the United States officially labeled me as a pirate although I was never actually charged with piracy. Nonetheless, a pirate I be,” Watson wrote, “and the great thing about pirates is that pirates cut through the red tape and the bureaucratic bs to get things done.”

It has taken 20 years of diplomatic negotiations, but the High Seas Treaty can be more than red tape. If ratified by 60 UN States, it, too, can get things done.

What the High Seas Treaty Does

The High Seas Treaty contains 75 articles that aim at protecting, caring for, and ensuring the responsible use of the marine environment, maintaining the integrity of ocean ecosystems, and conserving the inherent value of marine biological diversity.

The treaty covers four themes:

1 – marine genetic resources, including the fair and equitable sharing of benefits;

2 – area-based management tools, including the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs);

3 – environmental impact assessments (EIAs); and

4 – capacity building and transfer of marine technology.

The High Seas Treaty applies to the treatment of marine animals such as whales, sharks, turtles and tuna that recognize no boundaries and swim freely between national waters and the high seas.

Many governments and conservationists agree that the low level of protection now in place leaves marine species and ecosystems vulnerable to the impacts of unsustainable industrial and illegal fishing, shipping, and other human activities.

Even after the High Seas Treaty takes effect, all countries will remain responsible for the conservation and sustainable use of waters under their national jurisdictions, and the high seas will have added protection if enough countries ratify the treaty.

Under the overarching UNCLOS Convention, which entered into force on November 16, 1994, the term “High Seas” means “all parts of the sea that are not included in the exclusive economic zone, in the territorial sea or in the internal waters of a State, or in the archipelagic waters of an archipelagic State.”

The UNCLOS convention reserves the high seas “for peaceful purposes.”

The high seas are open to all States, whether coastal or land-locked. Freedom of the high seas for all States includes: freedom of navigation; freedom of overflight; and, subject to stated conditions, freedom of fishing, of scientific research, to lay submarine cables and pipelines, freedom to construct artificial islands and make other installations permitted under international law.

Under these conditions, scientific research has shown the vulnerability of marine creatures, particularly around seamounts, hydrothermal vents, sponges, and cold-water corals, while concerns grow about the increasing pressures posed by existing and emerging human activities: fishing, mining, marine pollution, and bioprospecting in the deep sea.

Although UNCLOS does not refer directly to marine biodiversity, it is commonly regarded as establishing the legal framework for all activities in the ocean.

Chile’s Story: the Humboldt Archipelago

Alberto Van Klaveren, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Chile, welcomed the new agreement and urged states to ratify and implement it as soon as possible. He noted that just benefit-sharing will require coordination and cooperation, and noted his country’s efforts to conserve the marine ecosystem, including through global efforts on regulating fisheries.

Van Klaveren reaffirmed his country’s’s offer to host the Secretariat of the new High Seas Treaty in the city of Valparaiso, one of the Pacific Ocean’s most important seaports and a UNESCO World Heritage Center.

Demonstrating how governments and conservation groups can work together to protect marine areas, Chile is moving forward with protections for the Humboldt Archipelago, a unique marine ecosystem just over an hour’s drive north of Valparaiso.

One of the most biodiverse and ecologically important parts of the Chilean coast and the southeast Pacific, the Humboldt Archipelago is the finest example of Humboldt Current kelp forests in the world, and is inhabited by 80 percent of the world’s endangered Humboldt penguins, and many other sea birds species, sea lions, sea otters, dolphins and orca. It is a summer feeding ground for endangered blue, fin and humpback whales.

On August 14, the nonprofit Oceana celebrated the new protected area, now known as the Humboldt Archipelago Multi-Use Marine Coastal Protected Area. The newly protected area covers more than 5,700 square kilometers located between the Atacama and Coquimbo regions. It was approved by the Council of Ministers for Sustainability in Chile.

“This is one of the most important environmental achievements in recent times in Chile, not only because it protects this biodiversity hotspot, but also because it protects economic activities such as artisanal fishing and tourism, which are essential in both regions,” said Liesbeth van der Meer, Oceana’s vice president in Chile.

“Over a decade ago, in collaboration with the scientific community and local communities, Oceana first proposed this marine protected area. Over time, civil society organizations and several entities came together to secure its protection and stand against more than five mega-projects that tried to develop in the area. It took four governments to assess this proposal, and finally, one made it a reality,” said van der Meer.

The Humboldt Archipelago is renowned for its abundant fishery resources, particularly its benthic resource management areas, which are the most productive in central-northern Chile and contribute 80% of abalone and limpet landings in the entire Coquimbo region. The area is also one of the few places in the country where whales and dolphins can be observed just a short distance from the coast, making it a wildlife tourism hotspot.

The Humboldt Archipelago contains ancestral fishing grounds for local communities and is a growing ecotourism destination, supported by a community that expressed a need for sustainable development and education about the treasures of the islands.

Oceana hopes Chile’s Humboldt Archipelago decision will protect the renowned biodiversity hotspot from threats like industrial development projects. Sustainable activities such as artisanal fishing and wildlife tourism will continue, in harmony with the area’s environment.

“Over the last 50 years, I have explored ocean ecosystems all over the world and what you can see at the Humboldt Archipelago is really extraordinary,” said Dr. Sylvia Earle, founder of the U.S. nonprofit Mission Blue. “A diver lucky enough to witness it, as I was in 2017, can see so much life, so many species in just a few minutes of being under the waves.”

If the new High Seas Treaty takes effect, by attracting signatures from at least 60 nations, similar marine protected areas can be established in the open oceans.

What About Mining the Seabed?

“One of the biggest debates in negotiating the treaty was the role of existing competent bodies,” said Arlo Hemphill, Greenpeace USA project lead for ocean sanctuaries and global corporate lead, Stop Deep Sea Mining Campaign, and a 20-year veteran of the high seas talks.

In a March interview with the U.S.-based nonprofit Oceanic Society, Hemphill named some of the existing bodies he means, “mostly fishery management bodies, but also including things like the International Seabed Authority, International Maritime Organization, OSPAR [Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic], Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, etc.”

“NGOs advocated for a strong treaty in which a Conference of Parties, COP, would have total power to implement the provisions of the agreement without having to defer to existing bodies that have largely failed us thus far. Fishery nations wanted all power of the new agreement going to those same bodies with the COP having no authority at all. The final agreement was a compromise between these two extremes,” Hemphill explained.

“This will be most relevant to the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs), as they will have to be joint ventures between the COP and the existing body in the region. So, where the treaty fully provides a pathway for a network of high seas MPAs, they won’t be instantaneous or easy. It will take a lot of effort and political will,” he predicted.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO, explained in 2021 that the ocean seabed holds “critical minerals that are both high in value and demand.”

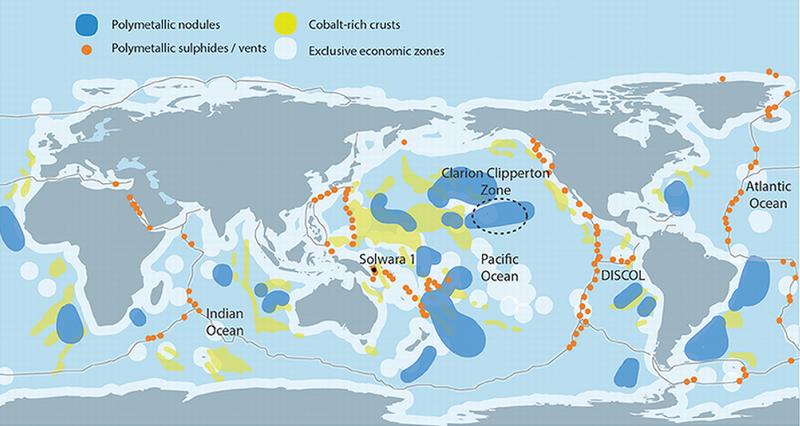

These critical minerals – cobalt, copper, nickel, and manganese – are used in cellphones and electric cars. But they are hard to come by, and the GAO expects demand to “double or triple by 2030.”

The deep sea holds potato-size nodules rich in manganese, cobalt, copper, nickel, and rare earth elements; deposits of minerals containing sulfur around underwater openings called hydrothermal vents; and cobalt-rich crusts lining the sides of mid-ocean ridges and seamounts.

Many of these deposits are located in international waters, and can be hundreds to thousands of miles from shore. In fact, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone spans 1.7 million square miles between Hawaii and Mexico, and it is a potential hotbed for critical minerals.

A number of countries, including the United States, and private companies have invested in technology to explore the deep-sea environment and locate potential mining sites. But no deep-sea commercial mining operations have been established yet.

Any future deep-sea mining efforts would need to overcome cold temperatures, extreme pressure, and lack of light.

“The designs for mining include remotely-operated extraction devices that dredge the ocean floor or seamount crust. Picture an underwater robot vacuuming the ocean floor, like a sea Roomba,” the GAO says.

“These extraction devices would attach to hydraulic lifting systems to carry the extracted material (nodules, sediment, and/or pieces of crust) to surface mining ships or floating platforms for minimal processing before being transferred to land for further refining,” the GAO explains.

In 2023 the International Seabed Authority, responsible for regulating mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction, is being pressured to finalize its exploitation regulations with the first exploitation application for polymetallic nodule mining in the Pacific to follow soon after.

Conservationist groups such as the U.S.-based Center for Biological Diversity are opposed to seabed mining, saying, “Mining interests plan to use large, robotic machines to excavate the ocean floor in a way that’s similar to strip-mining on land. The materials are pumped up to the ship, while wastewater and debris are dumped into the ocean, forming large sediment clouds underwater. The slurry is then loaded onto barges and shipped to onshore processing facilities.”

“The problem is that deep-sea mining operations will inevitably harm sensitive underwater ecosystems. Marine life threatened by the projects we’re challenging include endangered sea turtles (loggerhead, green, leatherback, hawksbill, olive ridley and flatback), sharks (grey reef, tiger, great hammerhead, and whitetip reef), tuna (frigate, mackerel, dog-tooth, yellowfin, albacore and bigeye), cetaceans (pygmy killer whale, sperm whale, spinner dolphin and Cuvier’s beaked whale) and marine birds (Beck’s petrel and Heinroth’s shearwater),” the Center for Biological Diversity says in a statement.

“The seafloor at the mining sites will be wiped clean of life and natural contours, directly affecting clams, mussels, corals, tubeworms, snails, xenophyophores, the larval supply, and basic enzymes and genetic resources,” the group warns.

As this technology matures, policymakers should weigh its benefits and costs and decide whether more research is needed to understand the environmental effects of seabed mining and potential ways to mitigate them.

For its part, the International Seabed Authority, ISA, is preparing for scientific study of the seabed – training technicians and selecting projects for funding.

The Board of the International Seabed Authority Partnership Fund, ISAPF, a multi-donor trust fund established last summer, has completed the selection of projects to be funded in 2023 during its first meeting held on June 1.

Their aim is “the implementation of the global deep-sea research agenda adopted unanimously by all ISA members in 2020 in support of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, and to contribute to dedicated capacity development programs and activities.

The ISAPF has a budget of about US$800,000 including new contributions from France, Greece, China and Mexico totalling $204,600.

Part of those funds will underwrite a training course on environmental impact assessment for exploration activities; capacity building for “least developed countries in deep-sea related sciences, technology and innovation in support of the sustainable development of blue emerging economies,” the ISAPF said.

More information is available at: https://www.isa.org.jm/partnership-fund.

Coastal Countries Join in Support

On June 19, after agreement on the final text of the treaty was reached, HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco praised all delegations for fulfilling the mandate put before them, working towards a sustainable future for the ocean. He underscored that UNCLOS was a visionary document now reinforced by the new High Seas Agreement. The prince emphasized that the Agreement breaks the status quo on the conservation and protection of the ocean from threats such as pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss.

Vivian Balakrishnan, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, called the BBNJ Agreement “a victory for international law, the global commons, and multilateralism in general.” He said that Singapore feels privileged to have been chosen to steer the process to its successful conclusion, and he called on governments to ratify the agreement when it opens for signature on September 20 at UN Headquarters in New York.

Carlos Sorreta, Undersecretary, Department of Foreign Affairs, the Philippines welcomed the inclusion of both monetary and non-monetary benefits, as well as the principle of the common heritage of humankind. He urged concerted action towards ratification of the Agreement that will be important for its speedy entry into force and implementation.

Abdulla Shahid, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Maldives, an island country in the north-central Indian Ocean, welcomed the agreement, which he said offers a framework to safeguard high seas biodiversity, linked to “the future wellbeing of the planet and future generations.”

September 18-20 is UN Summits Week. The 78th session of the UN General Assembly will feature a series of high-level events, including the Sustainable Development Goals Summit and the Climate Ambition Summit.

Observing that the adoption of the High Seas Treaty is “a historic step in international law,” Alejandro Celorio Alcántara, legal adviser, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mexico, called on the UN States to sign and ratify the agreement, expressing hope for its universal acceptance. He reaffirmed the principle of the common heritage of humankind as the main legacy left to future generations, noting that the adoption of this Agreement “closes the chapter, accomplishing the mission.”

The 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals were adopted in 2015 for accomplishment by 2030. At the half-way point, this summit’s purpose is to renew ambition and accelerate actions.

The summit will be preceded by an “SDG Action Weekend,” which will provide a platform for stakeholder engagement and feature high-level side events.

The Climate Ambition Summit is being convened by UN Secretary-General Guterres to demonstrate that there is collective will to accelerate the pace and scale of a just transition to a more equitable renewable-energy based, climate-resilient global economy. It will feature three tracks on ambition, credibility, and implementation. A Chair’s Summary will present the main outcomes of the Summit.

On September 20, at the close of UN Summit Week, the High Seas Treaty will be opened for signature.

Featured image: Humpback whale breaching in the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, 2014. (Photo by K. Grosskruetz courtesy NOAA)