MANCHESTER, UK, February 12, 2022 (ENS) – At least 50 local governing councils across England, Scotland, and Wales are worried about radioactive contamination in their communities, as about half of the UK’s current nuclear generating capacity is due for decommissioning by 2025.

The decommissioning process will separate the radioactive fuel rods that power the nuclear reactors from the rest of the structures for storage and reprocessing. It’s the reprocessing that worries the local governments because it creates nuclear waste.

The UK now has 11 operating nuclear reactors at five locations and roughly half of them will start decommissioning by 2025. But the one most worrisome to the councilors and mayors is not an operating nuclear generator, it is the world’s largest stockpile of plutonium under civil, not military, control. At Sellafield on the shore of the Irish Sea in Cumbria, the stockpile now stands at roughly 120 tonnes.

Those 50 communities have organized as the Nuclear Free Local Authorities of the UK and Ireland, NFLA, and they are calling for “Britain’s deadly plutonium stockpile to be labeled “out of use,” which does not appear to be an official classification, but the NFLA’s meaning is clear.

The group of local governments wants “an early end to reprocessing,” and “greater accountability and more transparency about the long-term management of radioactive materials arising from decommissioning operations at the country’s former nuclear power plants,” they said in a statement last week in response to the government’s request for public comment on its latest decommissioning business plan.

Once considered a valuable asset for reuse as fuel, the plutonium, most stored in tight security at the Sellafield nuclear plant in Cumbria, northwest England, is now seen as an expensive liability and a potential terrorist target.

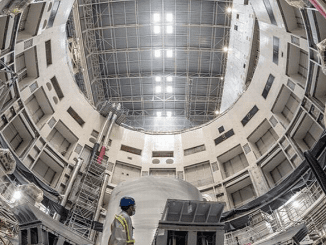

Originally a munitions factory producing plutonium for nuclear weapons in 1947, the British government transformed Sellafield into a working nuclear facility by 1960. Today, Sellafield covers six square kilometers and hosts more than 200 nuclear facilities.

The Thorp nuclear reprocessing plant at Sellafield was shut down in 2018. But the NFLA says the reprocessing is still going on at the B205 Magnox Reprocessing Plant at Sellafield. The B205 plant has had safety issues including a leak of radioactive condensation that went unnoticed for 12 months, according to the International Panel on Fissile Materials, which says that B205 operations have been the largest source of radioactive discharge to the Irish Sea from the Sellafield site.

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority’s Business Plan

In its comment, the Nuclear Free Local Authorities group expressed its “disappointment that reprocessing at Sellafield did not end in 2020 as was originally promised and that there is still no clear end date.”

The NFLA also wants to see a comprehensive inventory of all radioactive materials created for each nuclear site, including those arising from decommissioning operations, and for local authorities to be consulted over arrangements for their transport and management.

Councillor David Blackburn of Leeds City Council, a member of the Green Party who chairs the NFLA Steering Committee, said, “Reprocessing at Sellafield continues to pollute the marine environment of the North East Atlantic, and plutonium is perhaps the most-deadly material known to mankind.”

“As a result of our nuclear civil and defence programmes, and because past government policy invited other nations to send us their nuclear waste for reprocessing, we have a huge stockpile,” said Blackburn.

“Plutonium can be converted into nuclear weapons, and so in our view it should be made safe and placed out of use,” he said.

Sellafield Plutonium Will Take 1,000 Years to Degrade

The stockpile of nuclear waste at Sellafield is now a dangerous proposition, the local leaders warn.

Scientists at the University of Manchester say it will take around 100 years to decommission the facility, and more than 1,000 years for the legacy radioactive waste to degrade.

The University of Manchester is leading Sellafield Site Futures – a project funded by the UK Energy Research Centre. The focus is the Sellafield Nuclear Plant, which is being decommissioned at a cost between £60 and 140 billion over a 120-year period, with an end date of 2140.

Among the questions the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority is considering are what will be done about the waste currently stored on the site.

In the early days of nuclear technology, plutonium from reprocessed nuclear waste was stockpiled as a source of fuel for a new breed of experimental nuclear reactors. But in the 1990s, Britain canceled the reactor program due to cost and safety concerns with only a small amount of plutonium used.

The Sellafield stockpile grew again when Britain agreed to reprocess nuclear waste from other countries. The plan was to reprocess the waste into plutonium and send it back to its country of origin for a fee. But to date, the nine countries of origin are not clamoring to buy it back, so foreign-owned plutonium now accounts for a quarter of Britain’s entire plutonium stockpile, the BBC reports.

Add a New Coal Mine to the Mix

To complicate matters, West Cumbrian Mining wants to develop an underground and undersea coal mine off the Cumbrian coast and partially under the Irish Sea.

Although twice approved by Cumbria County Council, there is local opposition to the plan. More than 2,300 people objected along with Friends of the Earth, Keep Cumbrian Coal in the Hole, and the World Wide Fund for Nature, WWF.

The NFLA, too, worries about the potential impact on radioactive wastes on the Irish Seabed which derive from the Sellafield site. A Freedom of Information request by the KCCH group regarding the “expected subsidence” and resuspension of Sellafield’s radioactive wastes from the seabed as a result of the coal mine has gone to the Sellafield site for internal review.

Writing in “TheEnergyMix,” in January, Paul Brown reminded us that, “From its inception, the reprocessing works was a highly polluting plant, discharging contaminated water into the Irish Sea. Plutonium, cesium, and other radionuclides were sent out to sea in a mile-long pipeline.” Radioactivity was picked up in shellfish in Ireland, and as far away as Norway and Denmark. Brown says these discharges now have been “considerably cleaned up.”

The hopeful coal mine developer West Cumbrian Mining said in statement last August that its Woodhouse Colliery “…will be net carbon zero for all aspects of the mining process and delivery of the product to UK customers or port for onward shipping to European customers.”

This has been achieved, West Cambrian said, “by combining a series of proven & emerging technologies, including renewable electricity, methane gas capture and elimination, microgrid power generation, green bio-fuel and gold standard carbon offsetting.”

West Cumbrian says the Woodhouse Colliery project will create 532 direct and 1,618 indirect jobs and deliver new UK exports, which are forecast to reduce the UK balance of trade deficit.

The Local Authorities group also wants to create jobs, but not with a new coal mine. Instead, the NFLA wants renewable technologies to be located on former nuclear sites . Renewable energy could then be produced to power decommissioning operations on these sites, with any surplus exported to the National Grid, they suggest.

Councillor Blackburn said, “Installing green technologies would also provide additional jobs and opportunities for local people to train in the construction, installation and maintenance of renewable power. Employing local people also means less commuting and this will help the NDA achieve its goal of being a net zero (carbon) business.”

Waste Issues Plague Many UK Nuclear Plants

EDF, Électricité de France S.A., a French state-owned multinational electric utility, will begin decommissioning Britain’s Hinkley Point B nuclear power plant no later than July 15, 2022, the company said.

Matt Sykes, managing director of EDF Generation, said the company had originally hoped to operate the plant to March 2023, but cracks in the graphite blocks of the reactor cores makes an earlier shutdown necessary.

Hinkley Point B in Somerset, southwest England, began operation in 1976. It is capable of generating enough electricity to power 1.8 million homes.

And the final nuclear power station on the Kent coast closed ahead of schedule after problems within its reactors proved beyond repair.

Dungeness B shut for repairs in 2018, but had been projected to start producing electricity again. The closure marks the end of 50 years of generating nuclear power in the region, after the neighboring Dungeness A nuclear plant ended production in 2006.

The Dungeness B station is situated on the tip of a headland surrounded by the Dungeness National Nature Reserve in Kent, one of the largest shingle landscapes in the world, inhabited by some 600 species of plants, a third of all plants found in the UK.

It employs about 500 staff and 250 contractors onsite. Most jobs will continue through the defueling process, which could take up to 10 years, EDF said.

On the North coast of Scotland, the Dounreay nuclear establishment was the center of the UK’s fast reactor R&D programme from 1955 to 1994 and is currently being decommissioned.

In 2018 a contract was awarded to Cavendish Nuclear Limited to dismantle and demolish the Dounreay reactor. The fuel and heavy-water coolant have been removed, leaving the reactor vessel, supports and containment shell for final demolition.

Work is currently focused on the fuel element storage block, FESB, where irradiated fuel was stored after its removal from the reactor.

Fiona Forbes, project manager of Dounreay Site Restoration Ltd, said today, “Demolition of the reactor will be the biggest change to the Dounreay skyline since decommissioning began, and a major strategic achievement.

“The next phase of work, to surround the FESB with an atmosphere-controlled containment structure, is underway and will enable operators to demolish the reinforced concrete block,” Forbes said. “This is expected to be carried out using a remotely-operated demolition machine in the coming months.”

In Wales, there is only one nuclear power station, but it, too, has decommissioning issues. The Trawsfynydd nuclear power station is a decommissioned generating plant located in Snowdonia National Park in Gwynedd, Wales. Started in 1965, it was the only nuclear power station in the UK to be built inland, using cooling water from a built reservoir.

Trawsfynydd was closed in 1991. Its planned decommissioning by Magnox Ltd was expected to take almost 100 years, but in 2021 the Welsh Government arranged for the power station to be redeveloped using small-scale reactors.

The UK Government has stated its commitment to sustainable, carbon-free sources of energy as it seeks to achieve its 2050 net-zero carbon emissions target, and has confirmed that nuclear power has a role to play in the future energy mix of the country.

Featured image: Sellafield nuclear facility in Cumbria, northwest England. 2020 (Photo courtesy University of Manchester)

© 2022, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.