SEATTLE, Washington, January 30, 2022 (ENS) – At least 349 plumes of methane gas are bubbling up from the seafloor in Puget Sound, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, a University of Washington research team has discovered. The methane is rising right in front of the city of Seattle and along the ferry routes that serve the Seattle metropolitan area and surrounding islands.

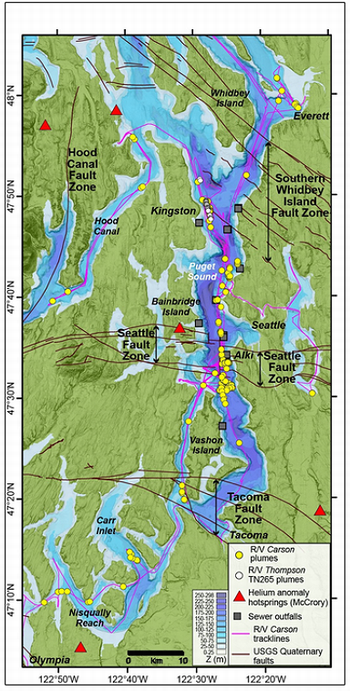

“These gas emission sites are co-located over traces of three major fault zones that fracture the entire forearc crust of the Cascadia Subduction Zone,” the UW scientists write in their new study in the January issue of the journal “Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.”

“Multibeam and single-beam sonar data from cruises conducted in years 2011, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 identified the acoustic signature of 349 individual bubble plumes. Dissolved CH4 [methane] gas from the plumes combines to elevate seawater methane concentrations of the entire Puget Sound estuary,” writes the UW team.

Methane is the primary contributor to the formation of ground-level ozone, a hazardous air pollutant and greenhouse gas. Human exposure to methane at ground level causes a million premature deaths every year, says the UN Environment Programme, UNEP.

Methane is also a powerful greenhouse gas. Over a 20-year period, said UNEP in a report last August, it is 80 times more potent at warming than carbon dioxide, the most abundant greenhouse gas.

While the columns of methane bubbles were seen dotted along the inside Puget Sound coastline, they are most numerous in two spots – offshore of Alki Point and offshore the Kingston ferry terminal.

Methane Bubbles Over Faults

The two persistent fields of bubble plumes occur above geologic faults, the scientists learned. The Alki bubbles are located above a branch of the Seattle Fault, and for the Kingston bubbles, above the South Whidbey Fault.

“It’s likely that the bubbles are connected to the underlying geology,” said Dr. Paul Johnson, the UW professor of oceanography who led the research team.

Alki, on the westernmost point of land in the West Seattle district, was the original 1850s settlement that was to become the city of Seattle. The Duwamish Tribe had inhabited this area for many centuries before white settlers came in the 1850s.

Today, two ferry runs, to Bainbridge Island and to Bremerton, leave and arrive from downtown Seattle a few miles to the north.

The other hotspot for methane plumes was found 23 miles north of Seattle, near the terminal in the small town of Kingston where a ferry takes passengers to and from Edmonds on the far shore.

“There’s methane plumes all over Puget Sound,” said Dr. Johnson, the study’s lead author. “Single plumes are all over the place, but the big clusters of plumes are at Kingston and at Alki Point.”

Previous UW research found methane bubbling up from the Pacific Ocean coastlines of Washington and Oregon. The bubbles in Puget Sound were first discovered by surprise in 2011, when the UW’s global research vessel, the RV Thomas G. Thompson, left its sonar beams turned on as it returned to its home port on the UW campus.

The underwater images created by the soundwaves showed distinct, persistent bubble plumes as the vessel rounded the Kingston ferry terminal.

Since then, the team analyzed sonar data collected during 18 cruises on the UW’s smaller research vessel, the RV Rachel Carson.

Methane plumes were seen from Hood Canal, to offshore of Everett, to south of the Tacoma Narrows. At Alki, the bubbles rise 200 meters (656 feet), about the height of the Space Needle, to reach the ocean’s surface.

“Off Alki, every three feet or so there’s a crisp, sharp hole in the seafloor that’s 3-5 inches in diameter,” Dr. Johnson said. “There are holes all over the place, but there aren’t bubbles or fluid coming out of all of them. There’s occasionally a burst of bubbles, and then another one 50 feet away that has a new burst of bubbles.”

The UW study is an early step toward exploring the release of methane from estuaries, or places where saltwater and freshwater meet, a subject more widely studied in Europe.

Though only a small amount of natural methane is released compared to human sources, understanding how the greenhouse gas cycles through ecosystems becomes increasingly important with climate change.

Johnson said, “In order to understand methane in the atmosphere and control the human sources, we have to know the natural sources.”

Puzzling Over What Emits the Gas

Questions remain about the bubbles’ origins. The idea that the bubbles might be coming from the Cascadia Subduction Zone was not supported. The gas bubbles don’t show the same distinctive chemistry as nearby hot springs and deep wells that connect to Subduction Zone deep underground.

Humans don’t appear to be responsible. While Puget Sound has in the past been a dumping ground for waste or sediment, vigorous tides sweep that material out into the open ocean, Johnson said. Nor do sewer outflows, gas lines and freshwater storm drains match the plumes’ locations.

Instead, a biological source of methane beneath the seafloor seems likely, Johnson observed.

“The source may be in the dense clay sediment deposited after the last Ice Age, when glaciers first carved out the Puget Sound basin,” he said. “The methane seems to be biological in origin, and the bubbles also support methane-eating bacterial mats in the surrounding water.”

In follow-up work, scientists used underwater microphones this fall to eavesdrop on the bubbles. The team also hopes to go back to Alki Point with a remotely operated vehicle that could place instruments inside a vent hole to fully analyze the emerging fluid and gas.

Susan Merle at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was on the research team. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Click here to access the study in Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, “Methane Plume Emissions Associated With Puget Sound Faults in the Cascadia Forearc.”

Featured image: Marine technician Sonia Brugger, right, and marine engineer Tor Bjorklund aboard the RV Rachel Carson collecting data near the Alki Point methane gas vent field. Alki Point is seen in the distance. Puget Sound, Washington, Decembeer 2020 (Photo courtesy University of Washington)