TOWNSVILLE, Queensland, Australia, May 31, 2016 (ENS) – One-third of the corals in the northern and central parts of the Great Barrier Reef are bleached out and dying due to climate change, according to Australian researchers. The scientists have just finished months of intensive aerial and underwater surveys that documented the worst-ever bleaching event in the reef’s history.

“We found on average, that 35 percent of the corals are now dead or dying on 84 reefs that we surveyed along the northern and central sections of the Great Barrier Reef, between Townsville and Papua New Guinea,” says Professor Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology says that this year the Great Barrier Reef recorded its highest-ever sea surface temperatures for February, March and April since recordkeeping began in 1900.

These record-breaking temperatures occurred because of the underlying ocean warming trend caused by climate change, the recent strong El Nino and local weather conditions, said the meteorologists.

The impact of the higher water temperatures changes from north to south along the 2,300 kilometer length of the world’s largest reef.

“Some reefs are in much better shape, especially from Cairns southwards, where the average mortality is estimated at only five percent,” said Hughes.

“This year is the third time in 18 years that the Great Barrier Reef has experienced mass bleaching due to global warming, and the current event is much more extreme than we’ve measured before,” he said.

“These three events have all occurred while global temperatures have risen by just 1 degree C above the pre-industrial period,” warned Hughes. “We’re rapidly running out of time to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

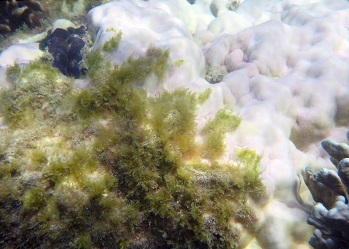

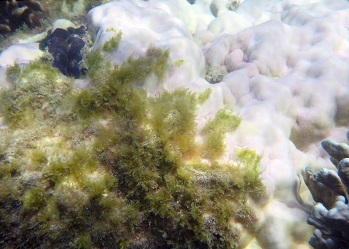

Coral bleaching occurs when abnormal environmental conditions, like heightened sea temperatures, cause corals to expel tiny photosynthetic algae, called zooxanthellae. The loss of these algae causes the corals to turn white.

Bleached out corals can recover if the temperature drops and zooxanthellae are able to recolonize them, otherwise the corals die.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority says, “Approximately 93 percent of surveyed reefs on the Great Barrier Reef have bleached to some extent, ranging from severe through to moderate and minor bleaching.”

“Fortunately, on reefs south of Cairns, our underwater surveys are also revealing that more than 95 percent of the corals have survived, and we expect these more mildly bleached corals to regain their normal colour over the next few months,” says Dr. Mia Hoogenboom from James Cook University.

Although fewer corals have died to the south, the stress of bleaching could temporarily slow down their reproduction and growth rates.

The reefs further south escaped damage because water temperatures there were closer to normal summer conditions than reefs to the north.

“It is critically important now to bolster the resilience of the reef, and to maximize its natural capacity to recover,” says Professor John Pandolfi from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at The University of Queensland.

“But the reef is no longer as resilient as it once was, and it’s struggling to cope with three bleaching events in just 18 years. “Many coastal reefs in particular are now severely degraded,” he said.

“In Western Australia, bleaching and mortality is also extensive and patchy,” says Dr. Verena Schoepf from the University of Western Australia.

“On the Kimberley coast where I work, up to 80 percent of the corals are severely bleached, and at least 15 percent have died already,” said Schoepf.

The scientists plan to re-visit the same reefs over the next few months to measure the final loss of corals from bleaching.

The recovery of coral cover is expected to take a decade or longer, but it will take much longer to regain the largest and oldest corals that have died.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2016. All rights reserved.

© 2016, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.