ZURICH, Switzerland, March 6, 2024 (ENS) – Transforming base materials into gold was one of the unachieved aims of ancient alchemists. But now Professor Raffaele Mezzenga from the Department of Health Sciences and Technology at the research university ETH Zurich has discovered how to recover gold from the base materials in discarded electronics using a byproduct of cheesemaking.

The fastest growing waste stream worldwide, in 2023 the world generated 61.3 million tonnes of electronic waste, up from 59.4 million tonnes the year before.

But this doesn’t have to be all waste, for the piles of outdated electronics contain valuable metals, such as gold, copper, cobalt, palladium and platinum. Recovering gold from obsolete smartphones and computers is attractive financially in light of rising demand for the precious metal.

Up to now, recovery methods have been energy-intensive and often require the use of toxic chemicals. But the group of scientists at ETH Zurich led by Professor Mezzenga has come up with an efficient, cost-effective, and more sustainable method.

With a sponge made from a protein matrix, the researchers have successfully extracted pure gold from electronic waste.

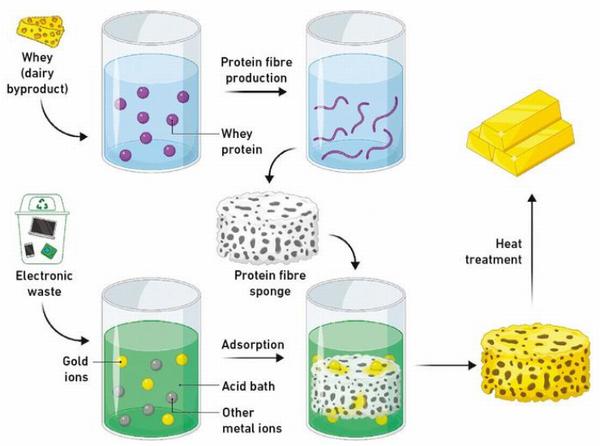

To manufacture the sponge, Mohammad Peydayesh, a senior scientist in Mezzenga’s group, and colleagues, denatured whey proteins under acidic conditions and high temperatures so they aggregated into protein nanofibrils in a gel. The scientists dried the gel, creating a sponge out of protein nanofibrils.

To recover gold in the laboratory, the team salvaged electronic motherboards from 20 old computers and extracted the metal parts, then dissolved them in acid to ionize the metals.

When they placed the protein fiber sponge in the metal ion solution, the gold ions adhered to the protein fibers.

Other metal ions can also adhere to the fibers, but gold ions do so much more efficiently. The researchers demonstrated this in their paper, published in the journal “Advanced Materials.”

In the next step, the researchers heated the protein fiber sponge. This reduced the gold ions to flakes, which the scientists then melted down into a gold nugget. In this way, they obtained a nugget of around 450 milligrams (0.0159 ounces or 1.59 percent of a ounce) out of the 20 computer motherboards.

This nugget, weighing 450-milligrams is 91 percent gold and nine percent copper, which corresponds to 22 carats. At today’s spot gold price, it is worth US$33.78.

The new technology is commercially viable, as Mezzenga’s calculations show. The energy costs of gold recovery amount to just one 50th of the value of the gold that can be recovered, making the new process very profitable if scaled up.

Next, the scientists want to develop the technology to prepare it for market. Although electronic waste is the most promising product from which they want to extract gold, there are other possible sources, such as industrial waste from gold-plating or microchip manufacturing.

In addition, the scientists plan to investigate whether they can manufacture protein fibril sponges out of other protein-rich byproducts or waste products from the food industry.

“The fact I love the most is that we’re using a food industry byproduct to obtain gold from electronic waste,” Mezzenga said. He observed that the new method transforms two waste products – e-waste and cheese waste – into gold. “You can’t get much more sustainable than that!”

For years Mezzenga has been researching the fusion of metals and proteins to create new forms of gold.

In 2020, Mezzenga and his team did invent a new form of the precious metal. A plastic gold that is 10 times lighter than natural gold and still has a fineness of 18 carats.

“Gold normally consists of 25 percent silver, palladium or copper. We have now replaced the 25 percent with plastic,” Mezzenga said, introducing the new material. There is a highly technical process behind this work. It could take several years until he has developed the process into a scalable technology. ETH has registered a patent for the new plastic gold.

The lighter gold could be used in jewelry and in electronic components. The plastic gold has the same value as natural gold, Mezzenga says. The market will determine that, but Mezzenga says, “If you were to build a small model of the Statue of Liberty, the model made of gold would have exactly the same carat as the model made of normal gold.”

Featured image: Professor Raffaele Mezzenga in his laboratory in the Department of Health Sciences and Technology at the public research university ETH Zurich, 2018 (Screengrab from video courtesy ETH Zurich)

© 2024, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.