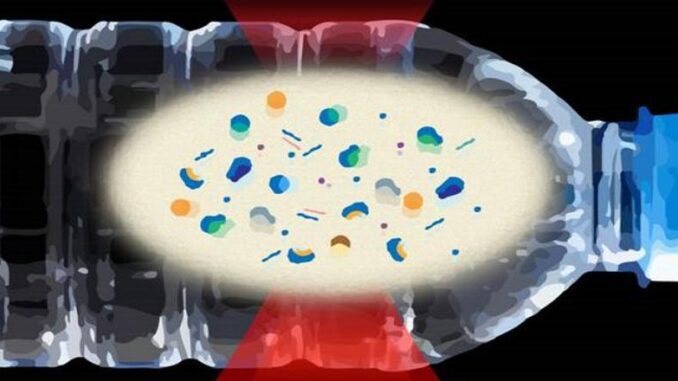

NEW YORK, New York, February 6, 2024 (ENS) – When we sip bottled water, we ingest not only water but hundreds of thousands of nanoplastic bits, scientists demonstrate in a newly published study in the journal “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.”

Nanoplastics are so small they can pass through the intestines and lungs and enter the bloodstream where they travel into the heart and brain. They can invade individual cells and cross through the placenta to the bodies of fetuses, the scientists warn.

Using the latest laser technology, scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health have, for the first time, identified and counted these minute nanoplastic particles in bottled water.

After analyzing three popular brands of bottled water [they declined to give brand names] for the presence of nanoplastics, the Columbia scientists found that on average, a liter of bottled water contained some 240,000 detectable plastic fragments.

They counted 110,000 to 370,000 plastic particles in each liter of bottled water, 90 percent of which were nanoplastics; the rest were microplastics.

This number is 10 to 100 times greater than previous estimates, which were based only on the much larger microplastic particles rather than on the nanoplastics that were the object of the latest analysis.

Microplastic fragments measure from the largest, five millimeters, less than a quarter of an inch, down to one millimeter, which is one-millionth of a meter, or 1/25,000th of an inch.

Nanoplastics are measured in billionths of a meter.

For comparison, a human hair is about 70 micrometers wide, but it takes between up to 100,000 nanometers to measure the width of that same human hair.

Unlike natural organic matter, most plastics do not break down into relatively benign substances, the Columbia scientists say. Plastics divide and redivide into smaller and smaller particles of the same chemical composition. Beyond single molecules, there is no theoretical limit to how small they can get.

Formed when microplastics break down, the nanoplastic particles in bottled water are being consumed by humans and many other creatures, with unknown potential effects on human health and the ecosystem.

The Columbia researchers are concerned but not surprised by the appearance of nanoplastics, as microplastics now are showing up everywhere on Earth, from polar ice to soil, from drinking water to food.

“Previously this was just a dark area, uncharted. Toxicity studies were just guessing what’s in there,” study coauthor Beizhan Yan, an environmental chemist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said.

“This opens a window where we can look into a world that was not exposed to us before,” he explained.

Now, medical scientists are racing to study the effects of nanoplastics on a host of biological systems.

Plastic Production Floods the World

Amongst all packaged or bottled beverages, bottled water has the highest level of consumption. Frequent bottled water drinkers are younger than the adult population as a whole, with the 35- to 44-year-old age group showing the highest likelihood of reaching for bottled water.

In 2023, the bottled water market worldwide generated a revenue of US$342 billion, big drop compared to previous years, probably due to the coronavirus pandemic and the restrictions and lockdowns that have come with it.

The global revenue in the bottled water segment of the non-alcoholic drinks market is forecast to continuously increase between 2023 and 2027 by at total of US$77.5 billion (+22.65 percent), according to Statista.

Worldwide plastic production is approaching 400 million metric tons a year, the Columbia researchers say. More than 30 million tons of plastics are dumped every year in water or on land, and many products made with plastics, including synthetic textiles, shed particles while still in use.

Scientists suspected there were even more plastic particles in bottled water than they had yet counted, but good estimates stopped at sizes below one micrometer – the boundary of the nano world.

“People developed methods to see nano particles, but they didn’t know what they were looking at,” said the study’s lead author, Naixin Qian, a Columbia graduate student in chemistry.

Previous studies could provide bulk estimates of nano mass, but could not count individual particles, nor identify which particles were plastics and which were not.

The new study employs a technique called “stimulated Raman scattering microscopy,” https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/MSD/brochures/Intro%20to%20Raman%20Brochure-BR50556-EN.pdf co-invented by study coauthor Wei Min, a Columbia biophysicist.

The technique involves probing samples with two simultaneous lasers that are tuned to make specific molecules resonate. Targeting seven common plastics, the researchers created a data-driven algorithm to interpret the results.

“It is one thing to detect, but another to know what you are detecting,” Min said. “There is a huge world of nanoplastics to be studied.”

Min noted that by mass, nanoplastics in a bottle of water are far less than the microplastics, but says, “It’s not size that matters. It’s the numbers, because the smaller things are, the more easily they can get inside us.”

The Columbia researchers analyzed plastic particles down to 100 nanometers in size. They determined which of the seven specific plastics they were, and charted their shapes – information that could be valuable in biomedical research.

Chemicals in Bottled Water Fragments Identified – a First

A common plastic found in the bottled water was polyethylene terephthalate or PET, a substance many water bottles are made of. It is also used for bottled sodas, sports drinks and products such as ketchup and mayonnaise.

PET probably gets into the bottled drinking water as bits break off when the bottle is squeezed or gets exposed to heat, the Columbia researchers say.

They cited one recent study suggesting that many particles enter the water when the bottle cap is repeatedly opened and closed and tiny bits of the plastic bottle abrade into the drinking water..

Still, the PET particles were outnumbered by particles of polyamide, a type of nylon.

Yan, the chemist, explained the polyamide probably comes from plastic filters used to “purify” the water before it is bottled.

Other common plastics the researchers found were: polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride and polymethyl methacrylate, all used in industrial processes.

The seven plastic types the researchers searched for accounted for only about 10 percent of all the nanoparticles they found in samples; they have no idea what the rest are.

If they are all nanoplastics, that means they could number in the tens of millions per liter.

But they could be almost anything, “indicating the complicated particle composition inside the seemingly simple water sample,” the authors write. “The common existence of natural organic matter certainly requires prudent distinguishment.”

The researchers now plan to analyze tap water, which also has been shown to contain microplastics, though far less than bottled water.

Yan is running a project to study microplastics and nanoplastics that end up in wastewater when people do laundry – by his count so far, millions per 10-pound load, coming off synthetic materials that comprise many items. He and colleagues are designing filters to reduce the pollution from commercial and residential washing machines.

The team will soon identify particles in snow that British collaborators trekking by foot across western Antarctica are currently collecting. They also are collaborating with environmental health experts to measure nanoplastics in various human tissues and examine their developmental and neurologic effects.

“It is not totally unexpected to find so much of this stuff,” said Qian. “The idea is that the smaller things get, the more of them there are.”

U.S. Bottled Water is Regulated

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates bottled water products, working to ensure that they’re safe to drink.

The FDA protects consumers of bottled water through the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which makes manufacturers responsible for producing safe, wholesome, and truthfully labeled food products.

There are regulations that focus specifically on bottled water, including:

- – “standard of identity” regulations that define different types of bottled water

- – “standard of quality” regulations that set maximum levels of contaminants—including chemical, physical, microbial, and radiological contaminants—allowed in bottled water

- – “current good manufacturing practice” (CGMP) regulations that require bottled water to be safe and produced under sanitary conditions

The FDA describes bottled water as water that’s intended for human consumption and sealed in bottles or other containers with no added ingredients, except that it may contain safe and suitable antimicrobial agents. Fluoride may also be added within the limits set by the FDA.

Some bottled water also comes from municipal sources – in other words, public drinking water or tap water. Municipal water is usually treated before it is bottled.

Water treatments may include:

- – Distillation. Water is turned into a vapor, leaving minerals behind. Vapors are then condensed into water again.

- – Reverse osmosis. Water is forced through membranes to remove minerals.

- – Absolute 1 micron filtration. Water flows through filters that remove particles larger than one micron – .00004 inches – in size. These particles include Cryptosporidium, a parasitic pathogen that can cause gastrointestinal illness.

- – Ozonation. Bottlers of all types of waters typically use ozone gas, an antimicrobial agent, instead of chlorine to disinfect the water. Chlorine can add residual taste and odor to the water.

Bottled water that has been treated by distillation, reverse osmosis, or another suitable process may meet standards that allow it to be labeled as “purified water.”

The FDA oversees inspections of bottling plants. The agency inspects bottled water plants under its general food safety program and has states perform some plant inspections under contract. Some states also require bottled water firms to be licensed annually.

Featured image: Using lasers, scientists have imaged hundreds of thousands of previously invisible tiny plastic particles in bottled water. 2024 (Photo by Naixin Qian, Columbia University)