WASHINGTON, DC, November 11, 2021 (ENS) – The interval between tropical storms making landfall along the U.S. Gulf Coast has been getting shorter over the past 40 years. By the end of the century, Louisiana and Florida will be twice as likely as they are now to experience two tropical storms that make landfall within nine days of each other, new scientific models predict.

As the global climate changes, more tropical storms have been packed into a single hurricane season, which in the Gulf region typically runs from June through November.

The time between storms in the region is shrinking, according to new findings published in the AGU journal “Geophysical Research Letters,” which publishes high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

“In previous research, people have mostly focused on the resilience of infrastructure, [rather than] the time to restore it after a storm,” said Dazhi Xi, a climate scientist at Princeton University who led the study, “Sequential Landfall of Tropical Cyclones in the United States: From Historical Records to Climate Projections.”

The research shows that Florida and Louisiana are most likely to experience “sequential landfall,” where one hurricane moves over land faster than infrastructure damaged in a previous storm can be repaired.

The researchers estimate this timescale between hurricanes to be 10 days for those states. Being hit by two storms in quick succession gives communities and infrastructure less time to recover between disasters, a real problem for a region with a swelling population that has struggled to recover following previous natural disasters.

With both a longer storm season and shorter breaks between disasters, stresses on infrastructure, ecosystems and people are intensified.

“If you need 15 days to restore infrastructure — for example, a power system — after a storm hits, and the second storm makes landfall before the system can recover, residents will face dangerous conditions,” said Xi. In a community without power, transportation or communications, problems around health risks, rescue and clean-up operations, and restoring systems are all exacerbated by sequential tropical storms.

Researcher Xi was joined on this study by Ning Lin, PhD, of Princeton’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, who this year won the Huber Civil Engineering Research Prize offered by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

She was chosen for “research that has led to significant advances in understanding risks associated with hurricanes and their impact on coastal infrastructure,” the prize jury said.

Dr. Lin was the first to quantify tropical cyclone storm surge flood hazards in a changing climate, employing climate and sea-level-rise projections, simulations, and high-resolution hydrodynamic modeling.

She recently extended these methods and developed flood hazard maps for the entire U.S. East and Gulf Coasts considering the current and future-projected climates, providing insights into the spatial and temporal variation of future-flood risks.

For the Sequential Landfall of Tropical Cyclones study, Xi and Lin examined hurricane seasons from 1979 to 2020, focusing on years in which at least two tropical storms made landfall in the same region within two weeks of each other.

Xi looked at how that number changed over time and paired that trend with a climate model to estimate how the number of back-to-back hurricanes would change over time.

The Princeton scientists broke down the Gulf Coast into different regions to identify which areas are most at risk of these sequential storms, historically and in the future. They found that Louisiana and Florida are the most likely places for multiple tropical storms to strike, but the entire coast will see more storms.

“The number of tropical storms is projected to grow rapidly even relative to the lengthening hurricane season,” Xi said.

Take August 2020, for instance. Hurricane Laura made landfall in Louisiana as a category 4, triggering a catastrophic storm surge of up to 18 feet above ground level. The storm killed dozens of people in the state and inflicted $17.5 billion in damage.

Two months later, Hurricane Zeta, a Category 3, left half a million people without power and caused $1.25 billion in damage.

In total, five named storms struck Louisiana in 2020. Louisiana has not yet recovered from two major hurricanes in 2020, but this summer, as the state was still dealing with the destruction from last year, another big hurricane blew toward the coast.

The damage from Category 4 Hurricane Ida from August 26 to September 4 threw Louisiana’s already ravaged infrastructure into chaos, caused 115 deaths and $65.25 billion in damage. It was the sixth most costly hurricane in U.S. history.

Sabarethinam Kameshwar, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Louisiana State University, said the repeat nature of hurricanes in the Gulf has taken a big toll on people’s lives. Many Lake Charles residents whose homes were flattened by recent disasters have spent months rebuilding and living in hotels or temporary shelters, he said. Some are still waiting for federal disaster aid to arrive.

“As these hurricanes happen back to back, there are multiple impacts for people whose houses got damaged during Laura,” Kameshwar told CNN. “A lot of those houses have still not been fixed yet, so for people who have already damaged houses, they might have further damages and [the hurricane] will make things worse for them.”

The need to focus on quicker restoration times after disasters was compounded earlier this year by an extreme cold snap in Texas in February, when much of the state’s power grid went offline.

That disaster was followed later by Tropical Storm Henri, which swamped New York’s subway system in August, and Hurricane Ida, which in September hit Louisiana, a state still “reeling” from last year’s hurricane season with three sequential landfalling storms, according to hurricane climatologist and geographer Jill Trepanier at Louisiana State University, who was not involved in the study.

“Even the best-case scenario of this worst-case scenario still spells devastation for the coast,” said Trepanier.

“That’s why climate refugees exist,” she said. “They’re people who are displaced because they can no longer live in an area due to changing climate conditions. If we’re unable to put power grid structures back in place, adequately house people, or provide water and other resources, we can’t have people living there.”

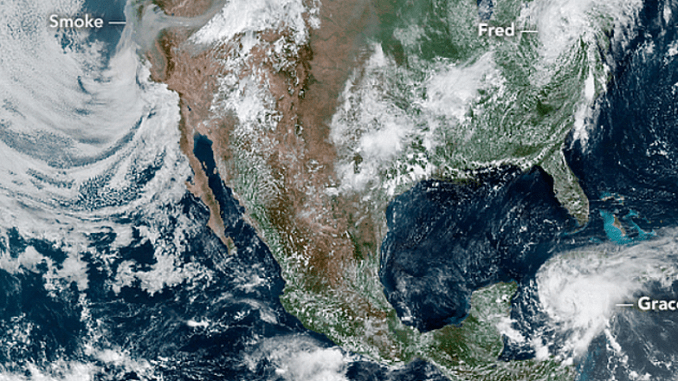

Featured image: Four different storms at various stages of development churned around the North American continent, August 18, 2021 NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using GOES 16 imagery courtesy of NOAA and the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service)

© 2021, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.