PENDLETON, Oregon, September 2, 2023 (ENS) – A Trump-era change in U.S. Forest Service regulations that permitted the logging of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest violates three separate laws, a federal judge in Oregon ruled August 31.

In a lawsuit filed by conservation groups over the change, U.S. Magistrate Judge Andrew Hallman found that the Forest Service violated the National Environmental Policy Act, the National Forest Management Act and the Endangered Species Act when it amended a protection for old-growth trees that had been in place since 1994.

The Forest Service issued its decision to allow logging of these big trees with a Finding of No Significant Impact in January 2021, in the final days of the Trump administration.

In his ruling, Judge Hallman disagrees with the Forest Service on the impact of logging the largest, oldest trees. “The highly uncertain effects of this project, when considered in light of its massive scope and setting, raise substantial questions about whether this project will have a significant effect on the environment,” the judge wrote.

Judge Hallman recommended that the Forest Service’s January 2021 decision be vacated and the Forest Service be required to prepare a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on the old-growth logging.

The Forest Service has two weeks to object to the judge’s findings and recommendations.

The conservation groups, with support from the Nez Perce Tribe, challenged the change to the Eastside Screens, a 30-year-old set of riparian, ecosystem, and wildlife standards for timber sales that apply to six national forests east of the Cascade Mountains: Colville, Deschutes, Malheur, Ochoco, Umatilla, Wallowa-Whitman, and Fremont-Winema National Forests.

The Screens protected trees measuring more than 21″ in diameter on 6.3 million acres of public lands.

While these large, old trees are the biggest three percent of all trees in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, still, they make up just three percent of those forests.

Yet that same three percent of Pacific Northwest trees – the largest and oldest – stores 42 percent of the regional forest carbon, concludes a 2020 study on forests in Oregon and Washington by scientists from universities in three states published in the journal, “Frontiers in Forests and Global Change.”

“Those trees also provide critical habitat for wildlife, keep water clean and cold, are resilient to wildfire, and are at the core of cultural values,” explained Chris Krupp of the plaintiff group WildEarth Guardians.

“The Forest Service rushed through a politically motivated rule change to log the most ecologically important trees left on our landscape. Sadly, this is in line with their well-earned reputation for putting logging before the need to address the climate and biodiversity crises,” Krupp wrote on the group’s website after Judge Hallman’s ruling.

“Just days before President Biden took office, a political appointee of the Trump administration illegally changed the rule and allowed those trees to be logged. The Forest Service was joined by the timber industry in defending the change,” he wrote.

The plaintiff groups who filed the lawsuit are all nonprofit corporations: the Greater Hells Canyon Council, Oregon Wild, and Central Oregon LandWatch – all based in Oregon; the Great Old Broads for Wilderness based in Montana, WildEarth Guardians in New Mexico, and the Sierra Club in California, represented by attorneys Meriel Darzen and Oliver Stiefel from the nonprofit Crag Law Center of Portland, Oregon.

In their filing, the groups alleged that the federal government’s environmental assessment did not address scientific uncertainty on the effectiveness of thinning large trees for reducing fire risk. The groups said the thinning and logging of large trees can increase fire severity.

In his ruling, Judge Hallman commented about the rule change, termed “the Screens Amendment,” approved by the defendant U.S. Forest Service. “Defendants argue in passing that these procedural violations ‘will not cause imminent harm in specific forests and project areas.’ But Plaintiffs have identified nine site-specific projects that will implement the Screens Amendment and declared that these projects will affect their use and enjoyment of the land because of the Amendment.”

The plaintiff groups pointed to evidence that large trees are critical to maintaining biodiversity and limiting climate change. They warned that eastern Oregon has few big trees trees remaining after “more than a century of high-grade logging.”

Rob Klavins, an advocate for Oregon Wild based in rural Wallowa County wants the public to have a say in the way the forests are managed in the future.

“We hope the Forest Service will take this decision to heart. As they go back to the drawing board, we expect them to meaningfully involve all members of the public to create a durable solution,” Klavins wrote. “That includes Tribes, local conservationists, and independent scientists who were all deliberately marginalized in the first process.”

On Earth Day, April 22, 2022, President Biden signed an Executive Order governing forest management on federal public lands, with an emphasis on conserving mature and old-growth forests.

It requires the Secretaries of Agriculture, which includes the Forest Service, and of the Interior to: “coordinate conservation and wildfire risk reduction activities, including consideration of climate-smart stewardship of mature and old-growth forests, with other executive departments and agencies, States, Tribal Nations, and any private landowners who volunteer to participate…”

The Secretaries are required to: “analyze the threats to mature and old-growth forests on Federal lands, including from wildfires and climate change; and develop policies, with robust opportunity for public comment, to institutionalize climate-smart management and conservation strategies that address threats to mature and old-growth forests on Federal lands.”

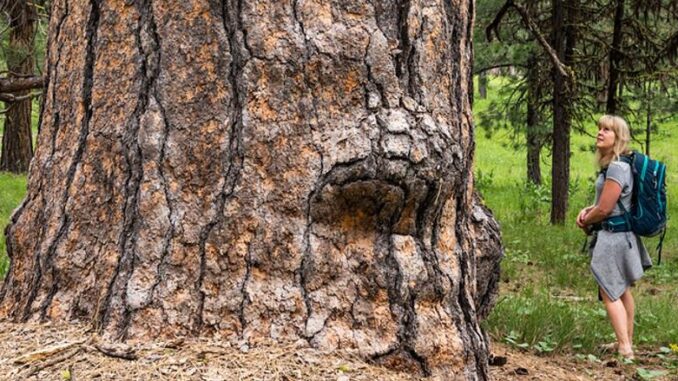

Featured image: Hiker stops to admire an old-growth ponderosa pine in the Ochoco National Forest. (Photo © Jim Davis used with permission)

© 2023, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.