DURHAM, UK, February 25, 2022 (ENS) – Astronomers from Durham University collaborating with a team of international scientists have mapped more than a quarter of the northern sky using the Low Frequency Array, LOFAR, a pan-European radio telescope. The map reveals a detailed radio image of more than 4.4 million galaxies and a dynamic picture of the Universe, which now has been made public for the first time.

To produce the map, scientists deployed state-of-the-art data processing algorithms on high performance computers all over Europe to process 3,500 hours of observations that occupy eight petabytes of disk space – the equivalent of roughly 20,000 laptops.

Durham University astronomer Dr. Leah Morabito said, “We’ve opened the door to new discoveries with this project, and future work will follow up these new discoveries in even more detail with techniques, which we work on here at Durham as part of the LOFAR-UK collaboration, to post-process the data with 20 times better resolution.”

Dr. Morabito describes one feature of the galaxies they mapped – active galactic nuclei. Her research focus is on answering fundamental questions about active galactic nuclei by investigating their radio properties, and using multi-wavelength information to place the radio information in context.

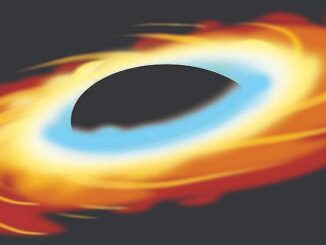

“A super-massive black hole exists at the centre of almost every massive galaxy,” she explains on the Durham University website. “The gravitational potential of these black holes can power highly energetic phenomena which are observed on sub-galaxy to galaxy cluster size scales, across the entire electromagnetic spectrum; when we observe these phenomena we know these are active galactic nuclei, AGN.”

“The basic picture of AGN that has emerged is of a black hole surrounded by an accretion disk, with a corona of hot gas, and the entire region is circled by a dusty torus. In some cases, AGN launch relativistic jets that extend far beyond the galaxy itself,” Dr. Morabito said. “But no matter how much energy an AGN outputs, the black hole powering it still remains a tiny part – both in physical size and total mass – of its host galaxy.”

Today’s data release, by far the largest from the LOFAR Two-metre Sky Survey, presents about a million objects that have never been seen before with any telescope and almost four million objects that are new discoveries at radio wavelengths.

Astronomer Timothy Shimwell of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, ASTRON, and Leiden University, said, “This project is so exciting to work on. Each time we create a map our screens are filled with new discoveries and objects that have never before been seen by human eyes.”

“Exploring the unfamiliar phenomena that glow in the energetic radio Universe is such an incredible experience and our team is thrilled to be able to release these maps publicly,” he said.

“This release is only 27 percent of the entire survey, and we anticipate it will lead to many more scientific breakthroughs in the future, including examining how the largest structures in the Universe grow, how black holes form and evolve, the physics governing the formation of stars in distant galaxies and even detailing the most spectacular phases in the life of stars in our own Galaxy,” Shimwell said.

The vast majority of these objects are billions of light years away and are either galaxies that harbour massive black holes or are rapidly growing new stars.

Rarer objects that have been discovered include colliding groups of distant galaxies and flaring stars within the Milky Way.

The scientists who worked on the project say this data presents “a major step forward in astrophysics” and can be used to search for a wide range of signals, such as those from nearby planets or galaxies right through to faint signatures in the distant Universe.

Featured image: The galaxy Hercules A is powered by a supermassive black hole located at its centre, which feeds on the surrounding gas and channels some of this gas into extremely fast jets. The new high-resolutions observations taken with the LOFAR show that this jet grows stronger and weaker every few hundred thousand years. This variability produces the beautiful structures seen in the giant lobes, each of which is about as large as the Milky Way galaxy. (Image credit: R. Timmerman; LOFAR & Hubble Space Telescope)

© 2022, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.