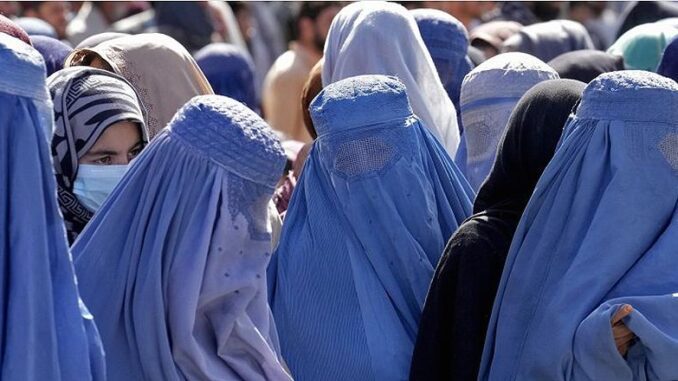

KABUL, Afghanistan, March 8, 2024 (ENS) – On this International Women’s Day, few women are on the streets of Afghan’s capital city, Kabul, and those that are out are with a male relative and covered from head to toe, according to the strict and strictly enforced rules of the Taliban government that took over when the United States and NATO pulled out of the country in the summer of 2021.

“There is broad consensus that the situation in Afghanistan is the most serious women’s rights crisis in the world, the nonprofit organization Human Rights Watch declares on this International Women’s Day, celebrated annually on March 8. Afghanistan is ranked last on the Women, Peace and Security Index, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Afghanistan has called out “the unprecedented deterioration of women’s rights.”

Richard Bennett is the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan since May 1, 2022. He has served in Afghanistan on several occasions in different capacities including as the Chief of the Human Rights Service with the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, UNAMA.

Currently a visiting professor at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law at Sweden’s Lund University, Bennett today called on the Taliban who control the country to release imprisoned women human rights defenders as the world marks International Women’s Day.

“On International Women’s Day, I stand with the women and girls of Afghanistan who face an unparalleled level of institutional and systematic discrimination. I salute their bravery, creativity and leadership as they demand their rights,” Bennett declared.

“I reiterate my appeal to the Taliban to respect all the human rights of women and girls in Afghanistan, including to education, work, freedom of movement and expression, and their cultural rights, and I urge the meaningful and equal participation of Afghan women and girls in all aspects of public life.”

“I call on the Taliban to immediately and unconditionally release all those who have been arbitrarily detained for defending human rights, especially the rights of women and girls,” Bennett demanded.

Afghan women – and officials at the UN and elsewhere – have called it “gender apartheid” of an intensity that has not been seen anywhere since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 75 years ago, except once, from 1996 to 2001, when the Taliban controlled Afghanistan and banned the education of females.

The United States and NATO troops withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021 following two decades of war, and the Taliban swiftly moved back in to rule the country of 43.5 million people, roughly half of them women and girls.

Now, more than two years after the Taliban’s September 2021 ban on girls attending school beyond the sixth grade, barring them from a high school education; now, after the Taliban forbade women to attend university at the end of 2023, Afghanistan is the only country in the world with restrictions on female education.

Other restrictions also narrow Afghan women’s lives. Recent Taliban crackdowns on women’s employment in the private sector, including ordering the closure of all beauty salons at a cost of 60,000 women’s jobs, signal a continuing assault on the livelihoods of Afghan women.

The closure of the beauty salons also signifies the loss of one of the very few women-only spaces outside the home – a crucial source of community and support, especially given that the Taliban has dismantled services for women and girls experiencing domestic violence, explains Human Right Watch, an international nongovernmental organization headquartered in New York City.

The Taliban’s ban on women working in most roles in aid agencies is putting more women and girls in crisis.

In Afghanistan’s increasingly gender-segregated society, if women workers are not there to deliver aid to women, they will often go without aid. Beyond blocking basic access to food, even the chance to walk in a park, play a sport, or enjoy nature are being stripped away from Afghanistan’s women and girls.

As of November 11, 2022, Afghan women are no longer allowed in parks, a spokesperson for the Taliban’s morality ministry said, in part because they had not been meeting its interpretation of Islamic attire during their visits.

On December 31, 2023, the Taliban Ministry of Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice started arresting young women and girls in Kabul, particularly in the western parts mainly populated by Shia/Hazara and Tajik communities, for “not observing the hijab.” It was unclear how many women were arrested and how many were missing, but the impacts were dramatic.

In much of the Arab and wider Muslim world, hijab refers to a woman covering her head, but in Afghanistan, it describes clothing that covers the head and body more fully. The Taliban’s decree defined the hijab as either a burqa or “customary black clothing and shawl” that is not too thin or too tight. The Taliban indicated that the best hijab is for women to not leave their homes at all, unless absolutely necessary.

Women described being frequently stopped and questioned by police who interrogated them on their movements, searched their mobile phones and bags, and, if they were speaking on the phone when they were stopped, demanded to know whom they were talking to. One woman reported that the police informed her that they sought to erase women from public spaces, step by step, according to the UN report.

UNAMA then consulted 28 Afghan women in Kabul. Several had directly witnessed de facto security forces rounding up women and girls in public spaces and transferring them to police stations, where they were told to call a male family member to pick them up. The male family member had to pay a fine and sign a document vouching that the woman would wear the full hijab in the future.

The arrests have had a visible chilling effect, resulting in a decrease in the number of women on the streets in Kabul. Women surveyed for the UN report overwhelmingly emphasized that the arbitrary, unexpected and severe enforcement of decrees left them feeling unsafe.

Women who protest these decrees face terrible consequences including enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention, and torture. From threats, beatings, and abusive conditions both during detainment and release, the Taliban continue to commit severe abuses against an ongoing – and underreported – string of women’s rights defenders.

Afghanistan today faces a constant flow of new restrictions against women and girls – and the Taliban are not done with their restrictions on the lives of women and girls.

“On March 8 I would like to ask you, free women in the world, to become our voice now that we are made silent, now that our hearts are cold and disappointed with life and our rights have been taken from us,” says a young Afghan woman and activist, whom we cannot name to protect her safety. “For us girls and women in Afghanistan life is now like a prison from which we do not have any hope of getting out, we do not see any light or warmth because no one holds our hands.”

Today, drastic erosion of women’s rights in Afghanistan continues. Women in Afghanistan say they fear arrest, harassment and further punishment, according to a new report by the UN’s International Organization for Migration, IOM; UN Women; and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, UNAMA, a UN Special Political Mission tasked with assisting the people of Afghanistan.

Since the August 2021 takeover, the Taliban, referred to in this report as the de facto authorities or DFA, have introduced more than 50 decrees that directly curtail the rights and dignity of Afghani women, according to a separate 2023 report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Based on an extensive survey of women across Afghanistan, the report says, “The Taliban’s vision for Afghanistan is founded on the structural denial of women’s rights, well-being and personhood.”

Police enforcement has increased harassment in public spaces and further limited women’s ability to leave their homes, according to testimony from 745 Afghan women participating in the survey by the three UN agencies.

Consultations took place between January 27 and February 8, with UN Women, IOM and UNAMA gathering views online and in-person, where it was safe to do so, and through group sessions and individual telesurveys. The agencies were able to reach women across all of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces.

Participants were asked to give their views on the period from October to December 2023.

The results show that women fear arrest and the long-lasting stigma and shame associated with being taken into police custody, the report states.

In addition, over half of women, 57 percent, felt unsafe leaving the house without a mahram, a male guardian. Risks to their security and their anxiety levels increased whenever a new decree was announced specifically targeting them.

Only one percent of Afghani women surveyed indicated that they had “good” or “full” influence on decision making at the community level, a decrease from 17 percent in January 2023.

A lack of any safe public space for women to gather and share views and experiences, build communities and engage on issues they considered important left them “without a pathway to participate in or influence decision making,” the report said.

Women’s self-reported “good” or “full” influence over household decisions has drastically decreased from 90 percent in January 2023 to just 32 per cent this January.

These women continued to link their lack of rights, educational prospects and jobs, to declining influence at home, the report found.

The women consulted for this report also outlined the intergenerational and gendered impact of the de facto authorities’ restrictions and the accompanying conservative shifts in social attitudes towards children.

Some respondents said boys appeared to be internalizing the social and political subordination of their mothers and sisters, reinforcing a belief that they should remain in the home in a position of servitude.

Meanwhile, girls’ perceptions of their prospects were changing their values and understanding of their future and potential, the report showed.

Women expressed dread and anxiety when asked to consider the possibility of international recognition of the Taliban’s government. A little over two-thirds (67 percent) said that recognition would have a significant impact on their lives. Under the current circumstances, it could exacerbate the women’s rights crisis and increase the risk that the Taliban would reinforce and expand existing restrictions targeting women and girls.

Roughly one-third of respondents to the UN survey said that international recognition of the de facto authorities should happen only after reversing all restrictions, while 25 percent of them said it should follow the reversal of some specific bans, and 28 percent said that recognition should not happen at all, under any circumstances.

In July 2023, a similar question found that 96 percent of women maintained that recognition should only occur after improvements in women’s rights or that it should not occur at all.

Respondents expressed deep disappointment with some UN Member States who in their efforts to engage the Taliban, were overlooking the severity of what is an unprecedented women’s rights crisis and the associated violations of international law, based on treaties ratified by previous Afghan governments.

Some respondents argued that one way for the international community to improve the situation of Afghani women would be to link international aid to better conditions for women and to provide opportunities for women to talk directly with the Taliban.

Several dozen men interviewed by the UN agencies reported no fear of the Taliban and no worry about going outdoors alone.

But making life more difficult for all, men and women alike, according to the World Food Programme, today, over half of the country’s population lives below the poverty line, and food insecurity is on the rise. In Afghanistan 15.8 million people suffer acute food insecurity, and one in three Afghans do not know where their next meal will come from.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned today that a “global backlash against women’s rights is threatening, and in some cases reversing, progress in developing and developed countries alike.”

“The most egregious example is Afghanistan, where women and girls have been barred from much of the education system, from employment outside the home, and from most public spaces,” he said.

“At our current rate of change, full legal equality for women is some 300 years away,” as is the end of child marriage, the UN chief predicted.

By 2030, over 340 million women and girls will still be living in extreme poverty, some 18 million more than men and boys, unless action is taken now, Guterres explained.

“That is an insult to women and girls, and a brake on all our efforts to build a better world,” he said. “We must drastically up the pace of change.”

Highlighting three priority areas for action to make investments in women and girls a reality, the Secretary-General said the first step is urgently increasing affordable, long-term finance for sustainable development.

The second step requires governments to prioritize equality for women and girls through such efforts as his newly launched plan, and the third action area, Guterres proposed, is to increase the number of women in leadership positions, which can help to drive investment in policies and programs that meet the needs of women and girls.

Featured image: Afghani women in burqas, August 2021, Kabul, Afghanistan (Photo courtesy AhlulBayt News Agency)

© 2024, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.