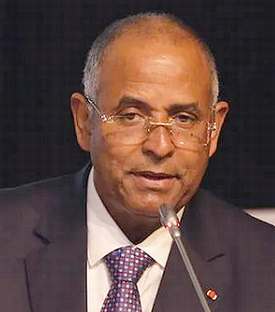

ABIDJAN, Côte d’Ivoire, May 23, 2022 (ENS) – “We all play a role in the common fight against climate change and land degradation, recognizing that a healthy and safe environment is vital to the future of the Earth,” said Côte d’Ivoire Prime Minister Patrick Achi on Friday, to delegates from 196 countries and the European Union, wrapping up a two-week summit to combat spreading deserts in a warming world.

At the summit, African heads of government expressed their frustration over barriers to funding the Great Green Wall that they are planting across the width of the continent to combat climate change and the spreading Sahara Desert. They warned that the impacts of climate change on the Sahel region are outpacing even the best-intentioned actions to address them.

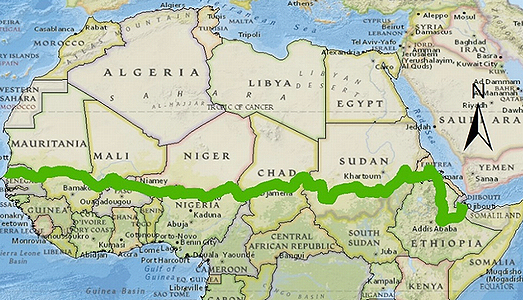

Spearheaded by the African Union and funded by the World Bank, the European Union and the United Nations, the Great Green Wall is planned as an 8,000 kilometer (5,000 mile) stretch of trees 15km wide planted coast to coast across the entire Sahel region from Dakar, Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east.

The Sahel region is one of the most vulnerable places on Earth, where the temperatures are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average and where increasing desertification, drought and resource scarcity are causing radicalization, conflict and migration.

The African-led movement to grow a wall of trees across the Sahel was expected to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land by 2030, creating jobs and food security for millions and capturing 250 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

But 15 years after its launch, the program has been hampered by financial barriers, lack of coordination among governments on a shared mechanism for monitoring progress, persistent land loss, and accelerating climate impacts.

These challenges shaped discussions among African leaders at the summit of the UN Convention on Combatting Desertification, UNCCD, in Abidjan. It’s the 15th conference of the parties to this treaty, known as COP15.

Right at the start of the summit, US$2.5 billion was raised for the Abidjan Legacy Programme launched by Côte d’Ivoire President Alassane Ouattara at the Heads of State Summit on May 9, which has already surpassed the US$1.5 billion anticipated for it, and that is helpful, but not enough.

Through the African Union, more than 20 African countries are involved in the Great Green Wall. They are: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, Algeria, Benin, Cape Verde, Egypt, Gambia, Libya, Somalia, and Tunisia.

Following the One Planet Summit organized by France last year, international donors pledged US$19 billion to support the activities of the African-led initiative. But today, more than a year later, the money still has not been disbursed. French President Emmanuel Macron was not at the Abidjan meeting to explain.

Other leaders of developed countries were not there either, but African heads of government left no doubt as to what is urgently needed – money.

President of Niger Mohamed Bazoum and Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari urged the donors to release the funds to support investments for smallholder farmers and capacity building. During the opening ceremony, President Bazoum painted a vivid image for his fellow heads of state of a vicious cycle of desertification, poverty and violence due to competition over resources.

The Great Green Wall is supposed to buffer Africa against the warming climate, and provide richer soil and attract moisture so that food crops can flourish.

“It’s not only planting trees, it’s planting hope for millions of young people,” said Ibrahim Thiaw of Mauritiania, executive secretary of the UNCCD.

“Hope is not yet turning into action at the scale or pace you aspire to,” Thiaw told African leaders during the COP15 talks in Abidjan. “Because collectively, we are struggling to turn those pledges into projects and investments. Understandably, this is leading to frustrations.”

“The principle reasons for the tragic worsening of this scourging remains ongoing desertification and the degradation of arable land,” Thiaw said, pointing out, too, that nearly half of the land best suited for regeneration is located in conflict zones.

Some heads of state and government at the talks expressed skepticism that yet another climate meeting would deliver positive change for Africa.

These summits “have created big hopes for Africa” in the past President of the African Union Commission Moussa Faki Mahamat of Chad told the meeting’s opening ceremony on May 9.

“But in truth, all these strategies and conferences haven’t achieved the expected results and the promises that underpinned them have not been met,” Mahamat said.

Markets Open for Sahelian Food Products

Positive economic changes are underway, too. UNCCD is a key partner of the Great Green Wall Initiative, working with businesses and major corporate partners to create green jobs and transform the Sahel through market-driven, sustainable ethical supply chains.

A new sourcing challenge was launched May 11 in Abidjan on the sidelines of COP15 at the Green Business Forum that will feature food and medicinal products grown in the Sahel region.

The Sahel sourcing challenge calls on the global supply chain managers to focus on the use of sustainably produced Sahelian ingredients, such as bambara nut, baobab, moringa, gum Arabic and fonio, from the Sahel’s small-scale producers as a way to create new economic opportunities for local populations.

Briefly, the bambara groundnut is a sustainable, low-cost source of complex carbohydrates, plant-based protein, unsaturated fatty acids, and essential minerals, especially for those living in arid and semi-arid regions. Named for the Bambara tribe, who at present live in Mali, this crop improves food security because it can tolerate harsh climatic conditions.

Bambara groundnuts are roasted or boiled. The seeds are milled into flour, baked to make small flat cakes and bread. In Eastern Africa, bambara groundnuts are roasted, milled, and the flour is used to make a soup, a relish, and a substitute for coffee.

Baobab grows throughout Africa and can be eaten fresh or used to add flavor and nutrients to desserts, stews, soups and smoothies.

Traditionally, baobab leaves, bark, and seeds have been used to treat many diseases: malaria, tuberculosis, fever, microbial infections, diarrhea, anemia, and toothache. The leaves and fruit pulp have been used to reduce fever and stimulate the immune system.

Moringa oleifera is a plant native to northern India that can also grow in Africa. The leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots of this plant have been used in folk medicine for centuries to treat diabetes, inflammation, bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, joint pain, heart health, and cancer.

Gum Arabic, used in the food and soft drinks industry as a stabilizer, is also used in lithography, printing, paint production, glue, cosmetics, and various industrial applications. It is harvested commercially from wild trees, mostly in Sudan and throughout the Sahel, from Senegal to Somalia.

Fonio is the name for two cultivated grasses, ancient heritage grains in the millet family, that are important crops in parts of West Africa. With a light nutty flavor and fluffy couscous-like texture, fonio is nutrient-rich and gluten-free with a low glycemic index.

Nick Salter, co-founder of Aduna, which buys, packages and markets these and other Sahelian crops, is inspired by the Great Green Wall project.

“The Great Green Wall challenge has a huge potential to help combat land degradation. By creating demand for the Sahel’s underutilized ingredients, the private sector can play a pivotal role in the creation of local economic development and the subsequent environmental and social impact that new value chains will bring,” Salter said.

Here’s how it works in practice. Through Aduna’s baobab supply chain, the company is working with over 2,300 women in Ghana and Burkina Faso who are benefiting from sustainable income streams where once there were none. Through Aduna’s wider supply chain, the company is working with hundreds more producers from all over Africa, including Mali, Malawi, Madagascar and Egypt.

“Our baobab supply chain is run in partnership with a local conservation NGO called ORGIIS who agrees fair pricing with the communities and works directly with the women to harvest and collect their fruits. We collect baobab fruits from 2,664 producers from 63 communities and employ a further 487 women to transform the fruits into powder. It is at this stage that we ship the powder to the UK. With this model, the added-value from the processing stays within the community and the income goes directly into the hands of the women,” Aduna says on its website.

Aduna, together with What If Foods, Unilever, Evonik, Doehler, the World Economic Forum, and the Global Shea Alliance, is among the businesses and platforms that are working on the challenge and calling on others to follow suit to make the challenge a world-class success.

“We’re looking to be not just buyers, but to support communities. Improving livelihoods and soil fertility are in everyone’s best interests,” says Scott Poynton, CEO and Founder of The Pond Foundation and What If Foods Partner.

The Accelerator

It’s important to do something quickly to save lives and livelihoods. The Sahel area – burdened with one of the planet’s most difficult biophysical ecosystems – has one of the world’s highest levels of multidimensional poverty, with poor indexes for health, schooling, and quality of life.

The 11 founding Great Green Wall countries all score below the average sub-Saharan Africa level on the Human Development Index, and population growth is projected to continue for the rest of the century, with Chad, Mali, Niger, and Senegal seeing growth rates of more than 2.5 percent in 2050.

With its pan-African reach and financial commitments both from governments in Africa and from international development partners, the Great Green Wall initiative has the potential to be a game-changer in the region.

The first appraisal survey, commissioned by the UNCCD and released in September 2020, indicates limited progress. Only four million hectares had been planted in the 11 founding member states – totaling only about 18 percent of the area the project aims to cover by 2030.

The Great Green Wall Initiative has evolved from its initial focus on tree planting towards a comprehensive rural development initiative aiming to transform the lives of Sahelian populations by creating a mosaic of green and productive landscapes across the 11 founding countries: Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti .

Today, almost 18 million hectares of degraded lands are restored and 350.000 jobs created across the Sahel and the Great Green Wall countries.

Over the period 2008-2019, Ethiopia accounted for more than half of the restored land in the project’s area of focus, followed by Niger at 20 percent, Eritrea with 15 percent, and Senegal with just three percent.

“The Great Green Wall is a movement for change,” said Tom Skirrow, chief executive with the British charity TreeAid. “Contributions to deliver its aims come from all sections of society – from the farmer who chooses to use agroforestry to improve his crops, to charities delivering large-scale restoration programs, to government efforts to deliver across entire regions.”

Even with these gains, a recent UNCCD report on the implementation status of the Great Green Wall highlighted at least four major challenges in achieving the project’s ambitions:

- – a lack of consideration in national environmental priorities

- – weak organizational structures and processes for the implementation

- – lack of mainstreaming of environmental change and action into the respective sector strategies, policies, and action plans,

- – insufficient coordination, exchange and flow of information at the regional and national levels.

The report estimates that at least US$33 billion will be required in the next decade to achieve the goals of the Great Green Wall by 2030 to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land, sequester 250 million tons of carbon, and create 10 million green jobs in rural areas.

Now the Accelerator is in place. The Accelerator will provide a comprehensive mapping of the available funding and monitor and evaluate the impact of projects. It will ensure a tracking of progress towards achieving the 2030 ambitions of the Great Green Wall.

The UNCCD will support the Pan African Agency of the Great Green Wall to monitor, track progress and ensure a more coordinated support to the existing Great Green Wall member states, structures and institutions.

And, the Accelerator will ensure that the financial commitments pledged at the One Planet Summit tackle and provide the solutions to the challenges that are currently slowing down progress for the Great Green Wall Initiative. And finally, the Accelerator pledges to mobilize both public and private financing to plant the Great Green Wall.

“The Great Green Wall is an inspiring example of ecosystem restoration in action,” said Susan Gardner, director of UNEP’s Ecosystems Division. “This initiative alone won’t transform the Sahel’s fortunes overnight, but it is rapidly becoming a green growth corridor that is bringing investment, boosting food security, creating jobs and sowing the seeds of peace.”

Featured image: Women planting in the Sahel. (Photo courtesy greatgreenwall.org)