Third-hand Tobacco Smoke Causes Cancer, Study Shows

BERKELEY, California, February 9, 2010 (ENS) – That stale cigarette smoke smell in hotel rooms and bars is more than annoying – it could be hazardous to your health, according to new research from a team led by scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Infants and toddlers are at greatest risk, the study reveals.

Nicotine in third-hand smoke, the residue from tobacco smoke that clings to surfaces long after a cigarette has been extinguished, reacts with the common indoor air pollutant nitrous acid to produce dangerous carcinogens, the study shows.

“The burning of tobacco releases nicotine in the form of a vapor that adsorbs strongly onto indoor surfaces, such as walls, floors, carpeting, drapes and furniture. Nicotine can persist on those materials for days, weeks and even months,” says Hugo Destaillats, a chemist with the Indoor Environment Department of Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Energy Technologies Division.

|

Coffee and cigarettes (Photo by Laura Domenico) |

“Our study shows that when this residual nicotine reacts with ambient nitrous acid it forms carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines or TSNAs,” said Destaillats. “TSNAs are among the most broadly acting and potent carcinogens present in unburned tobacco and tobacco smoke.”

“We know that these residual levels of nicotine may build up over time after several smoking cycles, and we know that through the process of aging, third-hand smoke can become more toxic over time,” says Destaillats.

The authors say theirs is the first study to quantify the reactions of third-hand smoke with nitrous acid.

In their lab tests, levels of newly formed TSNAs detected on cellulose surfaces were 10 times higher than those originally present in the sample after exposure for three hours to what they authors call a “high but reasonable” concentration of nitrous acid, 60 parts per billion by volume.

“Time-course measurements revealed fast TSNA formation, up to 0.4 percent conversion of nicotine within the first hour,” says lead author Mohamad Sleiman of Berkeley Lab’s Indoor Environment Department.

“Given the rapid sorption and persistence of high levels of nicotine on indoor surfaces, including clothing and human skin, our findings indicate that third-hand smoke represents an unappreciated health hazard through dermal exposure, dust inhalation and ingestion,” Sleiman said.

|

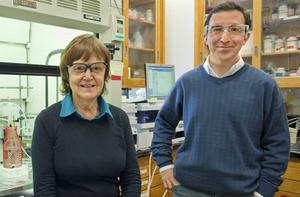

Scientists Lara Gundel and Hugo Destaillats at the Berkeley Lab’s Indoor Environment Department (Photo courtesy LLBL) |

Since the most likely human exposure to these TSNAs is through either inhalation of dust or the contact of skin with carpet or clothes, third-hand smoke would seem to pose the greatest hazard to infants and toddlers.

The study’s findings indicate that opening a window or using a fan to ventilate the room while a cigarette burns does not eliminate the hazard of third-hand smoke. Smoking outdoors is not much of an improvement, as co-author Lara Gundel explains.

“Smoking outside is better than smoking indoors but nicotine residues will stick to a smoker’s skin and clothing,” she says. “Those residues follow a smoker back inside and get spread everywhere. The biggest risk is to young children. Dermal uptake of the nicotine through a child’s skin is likely to occur when the smoker returns and if nitrous acid is in the air, which it usually is, then TSNAs will be formed.”

Unvented gas appliances are the main source of nitrous acid indoors. Since most vehicle engines emit some nitrous acid that can infiltrate the passenger compartments, tests were also conducted on surfaces inside the truck of a heavy smoker, including the surface of a stainless steel glove compartment. These measurements also showed substantial levels of TSNAs.

In both cases, one of the major products found was a TSNA that is absent in freshly emitted tobacco smoke the nitrosamine known as NNA. The potent carcinogens NNN and NNK were also formed in this reaction.

“Whereas the sidestream smoke of one cigarette contains at least 100 nanograms equivalent total TSNAs, our results indicate that several hundred nanograms per square meter of nitrosamines may be formed on indoor surfaces in the presence of nitrous acid,” said Sleiman.

|

Toxics remain long after cigarettes are extinguished. (Photo by Paul Douglas) |

“Nicotine, the addictive substance in tobacco smoke, has until now been considered to be non-toxic in the strictest sense of the term,” says Kamlesh Asotra of the University of California’s Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, which funded this study. “What we see in this study is that the reactions of residual nicotine with nitrous acid at surface interfaces are a potential cancer hazard, and these results may be just the tip of the iceberg.”

The dangers of mainstream and second-hand tobacco smoke have been well documented as a cause of cancer, cardiovascular disease and stroke, pulmonary disease and birth defects. But the threat posed by third-hand smoke has not been well understood.

The term third-hand smoke was coined in a study that appeared in the January 2009 edition of the journal “Pediatrics,” in which it was reported that only 65 percent of non-smokers and 43 percent of smokers surveyed agreed with the statement that “Breathing air in a room today where people smoked yesterday can harm the health of infants and children.”

Co-author James Pankow points out that the results of this study should raise concerns about the purported safety of electronic cigarettes, also called e-cigarettes.

Electronic cigarettes claim to provide the smoking experience, but without the risks of cancer. A battery-powered vaporizer inside the tube of a plastic cigarette turns a solution of nicotine into a smoky mist that can be inhaled and exhaled like tobacco smoke. Since no flame is required to ignite the e-cigarette and there is no tobacco or combustion, e-cigarettes are not restricted by anti-smoking laws.

The study, “Formation of carcinogens indoors by surface-mediated reactions of nicotine with nitrous acid, leading to potential third-hand smoke hazards.” is published in the current issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Co-authoring the PNAS paper with Destaillats, Sleiman, and Gundel is Brett Singer, also with Berkeley Lab’s Indoor Environment Department, plus James Pankow with Portland State University, and Peyton Jacob with the University of California, San Francisco.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2010. All rights reserved.

© 2010 – 2012, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.