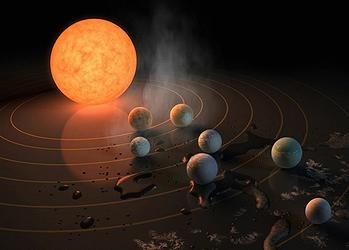

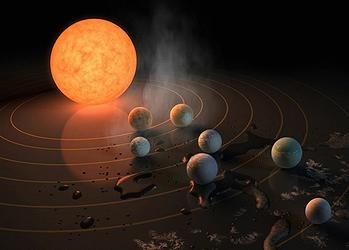

WASHINGTON, DC, February 25, 2017 (ENS) – Seven Earth-sized planets have been found by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope around a small, relatively nearby, ultra-cool dwarf star. Three of these planets are located in the habitable zone, the area around the parent star where a rocky planet is most likely to have liquid water, a necessity for life like that on Earth.

The discovery sets a new record for greatest number of habitable-zone planets ever seen around a single star outside our solar system.

“This discovery could be a significant piece in the puzzle of finding habitable environments, places that are conducive to life,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

“Answering the question ‘are we alone’ is a top science priority and finding so many planets like these for the first time in the habitable zone is a remarkable step forward toward that goal,” Zurbuchen said.

At about 40 light-years, or 235 trillion miles, from Earth, the system of planets is relatively close to us, in the constellation Aquarius. Because they are located outside of our solar system, these planets are known as exoplanets.

This exoplanet system is called TRAPPIST-1, named for the ground-based Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile, the instrument through which three of them were first viewed.

In May 2016, researchers using TRAPPIST announced they had discovered three planets in the system. Assisted by several ground-based telescopes, including the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, Spitzer confirmed the existence of two of these planets and discovered five additional ones, increasing the number of known planets in the system to seven.

The new results were published Wednesday in the journal “Nature,” and announced at a news briefing at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

The mass of the seventh and farthest exoplanet has not yet been estimated. Scientists believe it could be an icy, “snowball-like” world, but further observations are needed.

Based on their densities, the scientists say all of the TRAPPIST-1 planets are likely to be rocky. Further observations will help determine whether they are rich in water, and also possibly reveal whether any could have liquid water on their surfaces.

Using Spitzer data, the team precisely measured the sizes of the seven planets and developed first estimates of the masses of six of them, allowing their density to be estimated.

“The seven wonders of TRAPPIST-1 are the first Earth-size planets that have been found orbiting this kind of star,” said Michael Gillon, lead author of the paper and the principal investigator of the TRAPPIST exoplanet survey at the University of Liege, Belgium.

“It is also the best target yet for studying the atmospheres of potentially habitable, Earth-size worlds,” he said.

In contrast to our sun, the TRAPPIST-1 star – classified as an ultra-cool dwarf – is so cool that liquid water could survive on planets orbiting very close to it, closer than is possible on planets in our solar system.

All seven of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary orbits are closer to their host star than Mercury is to our sun. The planets also are very close to each other.

NASA says that if a person was standing on one of the planet’s surface, he or she could gaze up and potentially see geological features or clouds of neighboring worlds, which would sometimes appear larger than the moon in Earth’s sky.

The planets may also be tidally locked to their star, which means the same side of the planet is always facing the star, therefore each side is either perpetual day or night.

This could mean they have weather patterns totally unlike those on Earth, such as strong winds blowing from the day side to the night side, and extreme temperature changes.

Spitzer, an infrared telescope that trails Earth as it orbits the Sun, was well-suited for studying TRAPPIST-1 because the star glows brightest in infrared light, whose wavelengths are longer than the eye can see. In the fall of 2016, Spitzer observed TRAPPIST-1 nearly continuously for 500 hours.

Spitzer is uniquely positioned in its orbit to observe enough crossing – transits – of the planets in front of the host star to reveal the complex architecture of the system.

Engineers optimized Spitzer’s ability to observe transiting planets during Spitzer’s “warm mission,” which began after the spacecraft’s coolant ran out as planned after the first five years of operations.

“This is the most exciting result I have seen in the 14 years of Spitzer operations,” said Sean Carey, manager of NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California. “Spitzer will follow up in the fall to further refine our understanding of these planets so that the James Webb Space Telescope can follow up. More observations of the system are sure to reveal more secrets.”

Following up on the Spitzer discovery, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has initiated the screening of four of the planets, including the three inside the habitable zone. These observations aim at assessing the presence of puffy, hydrogen-dominated atmospheres, typical for gaseous worlds like Neptune, around these planets.

“The TRAPPIST-1 system provides one of the best opportunities in the next decade to study the atmospheres around Earth-size planets,” said Nikole Lewis, co-leader of the Hubble study and astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler space telescope also is studying the TRAPPIST-1 system, making measurements of the star’s minuscule changes in brightness due to transiting planets. Operating as the K2 mission, the spacecraft’s observations will allow astronomers to refine the properties of the known planets, as well as search for additional planets in the system.

The K2 observations conclude in early March and will be made available through NASA’s public archive.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2017. All rights reserved.

© 2017, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.