WASHINGTON, DC, October 14, 2022 (ENS) – “The roar of the jaguar could be heard near the community three years ago, but not anymore. Compared with my childhood, I’ve witnessed a big difference. The animals in the community are now gone,” mourns Flor Delicia Ramos Barba. She feels the loss of nature in the Indigenous community of Santo Corazon in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, where she lives.

“We also feel this lack in the rivers. The people used to go fishing to support their families, but now there are no fish. Tree species have also been disappearing,” Ramos Barba tells wildlife researchers.

The Indigenous community of Santo Corazon is by no means alone in losing wildlife, many species that were plentiful a mere 48 years ago.

From 1970 to 2018, monitored populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish have dropped by 69 percent on average, according to the Living Planet Report 2022.

Based on some 32,000 populations of over 5,200 species compiled by the Zoological Society of London, this comprehensive study of trends in global biodiversity and the health of the planet was issued Thursday by the nonprofit World Wildlife Fund, WWF.

Wildlife populations in Latin America and the Caribbean have fared worst, with an average decline of 94 percent, the study finds, and global freshwater species have also been heavily impacted, declining 83 percent on average.

Wildlife populations in Africa are experiencing average declines of around 66 percent, the data shows.

The report identifies the main drivers of wildlife decline – habitat loss, species overexploitation, invasive species, pollution, climate change, and diseases.

“The world is waking up to the fact that our future depends on reversing the loss of nature just as much as it depends on addressing climate change. And you can’t solve one without solving the other,” says Carter Roberts, president and CEO of WWF-US. “Everyone has a role to play in reversing these trends, from individuals to companies to governments.”

WWF is calling on policymakers to transform economies so that natural resources are properly valued. As biodiversity loss and climate change share many of the same underlying causes, actions that transform food production and consumption, rapidly cut emissions, and invest in conservation can help to reverse both difficult situations.

“These plunges in wildlife populations can have dire consequences for our health and economies,” says Rebecca Shaw, global chief scientist of WWF. “When wildlife populations decline to this degree, it means dramatic changes are impacting their habitats and the food and water they rely on. We should care deeply about the unraveling of natural systems because these same resources sustain human life.”

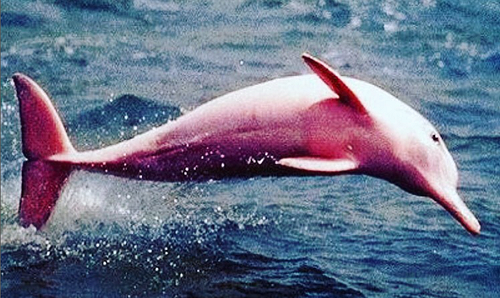

Some of the species captured in the Living Planet Index include the Amazon pink river dolphin, which saw populations plummet by 65 percent between 1994 and 2016 in the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve in the Brazilian state of Amazonas.

Numbers of the eastern lowland gorilla declined 80 percent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Kahuzi-Biega National Park between 1994 and 2019.

Numbers of sea lion pups on the coasts of South and Western Australia plunged by two-thirds between 1977 and 2019.

Big Biodiversity Conference on the Horizon

World leaders will meet at the 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD COP15) in December for an opportunity to make changes that might benefit wildlife, people and the planet. The conference will be held December 7 – 19 in Montreal, Canada to decide upon the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

Dr. Robin Freeman, Head of Indicators & Assessments Unit at the Zoological Society of London, said, “Governments meeting this December in Montreal have the opportunity to secure the health of species and restore ecosystems, to ensure a future for nature across the globe. ZSL is calling on world leaders to put nature at the heart of all global decision-making at COP 15, by making stronger targets and commitments to reverse biodiversity loss – and urge them to include the LPI as a headline indicator through which to hold these targets to account.”

WWF says the U.S. government can help ensure that COP15 and the emerging 2030 Global Biodiversity Framework are successful through its diplomatic engagement and by bringing new resources to the table to help developing countries protect their biodiversity.

“In the United States, Congress should finalize this year’s funding bills with significant increases for global conservation programs,” Roberts said. “Doing so would empower the federal government to drive greater progress in conserving and restoring nature, and send a signal to other countries that it expects other actors to do the same.”

Nature Under Pressure

The Living Planet Index is an early warning indicator of the health of nature. This year’s edition analyzes almost 32,000 species populations with more than 838 new species and just over 11,000 new populations added since the 2020 edition.

It provides a comprehensive measure of how wildlife is responding to environmental pressures driven by biodiversity loss and climate change, while also allowing us to better understand the impact of people on biodiversity.

The Living Planet Report 2022 emphasizes that recognizing and respecting the rights, governance, and conservation leadership of Indigenous peoples and local communities is essential for delivering a nature-positive future.

Flor Delicia Ramos Barba says her Indigenous community of Santo Corazon in Bolivia, really feels the loss of nature. “As a community we have become aware of the difficulties that come our way year after year. The conservation of our territory is important to us.”

Featured image: Hyacinth macaws perch on a fence in Santo Corazon, Santa Cruz, Bolivia (Photo courtesy clb foundation, Santo Corazon, Santa Cruz, Bolivia via Instagram)

© 2022, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.