LONDON, UK, March 1, 2017 (ENS) – Direct evidence of the oldest life forms ever found on Earth – the fossilized remains of microorganisms at least 3,770 million years old – has been discovered by an international team led by scientists with the University College London, UCL.

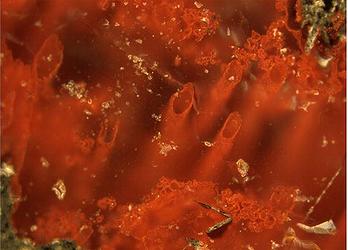

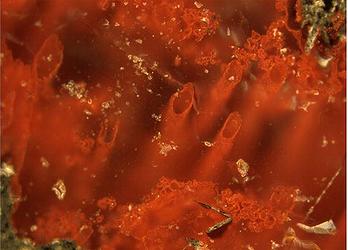

Tiny filaments and tubes formed by bacteria that lived on iron were found encased in quartz layers in the Nuvvuagittuq Supracrustal Belt, NSB, in the province of Quebec in eastern Canada.

The NSB contains some of the oldest sedimentary rocks known on Earth. The scientists say they likely formed part of an iron-rich deep-sea hydrothermal vent system that provided a habitat for Earth’s first life forms between 3,770 and 4,300 million years ago.

“Although it is not known when or where life on Earth began, some of the earliest habitable environments may have been submarine-hydrothermal vents,” the authors write in the journal “Nature,” where the study was published today.

“Our discovery supports the idea that life emerged from hot, seafloor vents shortly after planet Earth formed,” said the study’s first author, PhD student Matthew Dodd with UCL Earth Sciences and the London Centre for Nanotechnology.

“This speedy appearance of life on Earth fits with other evidence of recently discovered 3,700 million year old sedimentary mounds that were shaped by microorganisms,” he said.

The study describes the discovery and the detailed analysis of the fossil remains undertaken by the team from UCL, the Geological Survey of Norway, U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Western Australia, the University of Ottawa and the University of Leeds.

“The structures are composed of the minerals expected to form from putrefaction, and have been well documented throughout the geological record, from the beginning until today,” said the study lead, Dr. Dominic Papineau, with UCL Earth Sciences and the London Centre for Nanotechnology.

“The fact we unearthed them from one of the oldest known rock formations, suggests we’ve found direct evidence of one of Earth’s oldest life forms,” he said.

Before this discovery, the oldest microfossils reported were found in Western Australia. They were dated at 3,460 million years old, but some scientists think they might be non-biological artefacts in the rocks.

So, it was a priority for the UCL-led team to determine whether the remains from Canada had biological origins.

The researchers looked at the ways the tubes and filaments of haematite – a form of iron oxide or rust – could have been made through non-biological methods such as temperature and pressure changes in the rock during burial of the sediments, but found all of the possibilities unlikely.

The haematite structures have the same characteristic branching of iron-oxidizing bacteria found near other hydrothermal vents today.

They were found alongside graphite and the minerals apatite and carbonate, which are found in biological matter including bones and teeth and are frequently associated with fossils.

The researchers also found that the mineralized fossils are associated with spheroidal structures that usually contain fossils in younger rocks.

This suggests that the haematite most likely formed when bacteria that oxidized iron for energy were fossilized in the rock.

“We found the filaments and tubes inside centimeter-sized structures called concretions or nodules, as well as other tiny spheroidal structures, called rosettes and granules, all of which we think are the products of putrefaction,” said the study lead, Dr. Dominic Papineau, with UCL Earth Sciences and the London Centre for Nanotechnology.

“They are mineralogically identical to those in younger rocks from Norway, the Great Lakes area of North America and Western Australia,” he explained.

“This discovery helps us piece together the history of our planet and the remarkable life on it, and will help to identify traces of life elsewhere in the universe,” said Papineau.

Dodd concluded, “These discoveries demonstrate life developed on Earth at a time when Mars and Earth had liquid water at their surfaces, posing exciting questions for extra-terrestrial life. Therefore, we expect to find evidence for past life on Mars 4,000 million years ago, or if not, Earth may have been a special exception.”

The research was funded by UCL, the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Carnegie of Canada and the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2017. All rights reserved.