GENEVA, Switzerland, October 29, 2012 (ENS) – As the changing climate brings more extreme weather – hurricanes, floods and drought – human health hazards are increasing, warn the world’s top health and weather officials. The “Atlas of Health and Climate,” published today jointly by the World Health Organization and the World Meteorological Organization, pinpoints the most pressing current and emerging challenges.

The “Atlas of Health and Climate” gives practical examples of how the use of weather and climate information can protect public health. Its publication today marks a new collaboration between the international public health and meteorological communities.

“This Atlas is an innovative and practical example of how we can work together to serve society,” said Michel Jarraud, secretary-general of the World Meteorological Organization, WMO.

The Atlas was released at a three-day Extraordinary Session of the World Meteorological Congress that opened today in Geneva. Here, delegates from the WMO’s 183 member governments will discuss the structure and implementation of the draft Global Framework for Climate Services.

A United Nations-wide initiative spearheaded by WMO to strengthen the provision of climate services to the benefit of society, especially the most vulnerable, the framework focuses on top four priorities – health, food security, water management and disaster risk reduction.

Hurricanes, cyclones, floods and drought affect the health of millions of people each year. Climate variability and extreme conditions such as floods can trigger disease epidemics – diarrhea, malaria, dengue and meningitis – which cause death and suffering for millions more.

“Prevention and preparedness are the heart of public health. Risk management is our daily bread and butter. Information on climate variability and climate change is a powerful scientific tool that assists us in these tasks,” said Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, WHO.

“Climate has a profound impact on the lives, and survival, of people,” said Dr. Chan. “Climate services can have a profound impact on improving these lives, also through better health outcomes.”

For instance, the Atlas shows how information on unusual rainfall events, overlaid on a map with 2010 reported cholera cases from the countries where access to water and sanitation remains poor, indicate priority areas for further research and health intervention.

Until now, Chan and Jarraud agree, climate services have been an underutilized resource for public health. But where these services have been utilized they have been effective. Case studies in the new Atlas illustrate how collaboration between meteorological, emergency and health services is already saving lives.

For example, the death toll from cyclones of similar intensity in Bangladesh has been reduced from around 500,000 in 1970, to 140,000 in 1991, to 3,000 in 2007, due to improved early warning systems and preparedness.

“Stronger cooperation between the meteorological and health communities is essential to ensure that up-to-date, accurate and relevant information on weather and climate is integrated into public health management at international, national and local levels,” said Jarraud.

Heat extremes now expected to occur only once in 20 years, may occur every two to five years by the middle of this century, the officials project.

At the same time, the number of older people living in cities will almost quadruple globally, from 380 million in 2010, to 1.4 billion in 2050. Cooperation between health and climate services can create measures to better protect people in this vulnerable group from heat stress during periods of extreme weather.

“Shifting to clean household energy sources would both reduce climate change, and save the lives of some 680,000 children a year from reduced air pollution,” they said.

The Atlas also shows how meteorological and health services can collaborate to monitor air pollution and its health impacts.

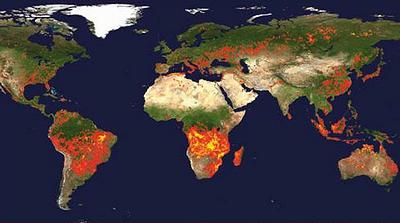

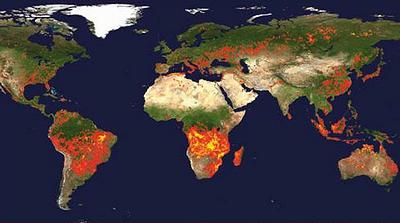

Maps, tables and graphs assembled in the Atlas make the links between health and climate clear. In some locations the incidence of infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue, meningitis and cholera can vary by factors of more than 100 between seasons, and can vary greatly between years, depending on weather and climate conditions.

Stronger climate services in countries where these diseases are endemic can help predict the onset, intensity and duration of outbreaks, said Jarreau and Chan.

The unique Atlas also shows how the relationship between health and climate is shaped by other vulnerabilities, such as those created by poverty, environmental degradation, and poor infrastructure, especially for water and sanitation.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2012. All rights reserved.

© 2012, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.