WASHINGTON, DC, March 7, 2014 (ENS) – President Barack Obama’s budget request for Fiscal Year 2015 withdraws federal funding for a long-delayed project to turn weapons-grade plutonium into fuel for nuclear reactors.

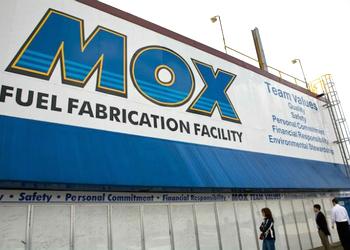

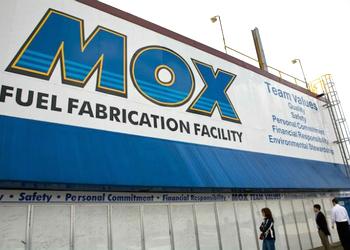

The Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication facility, currently under construction at the Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina, would convert plutonium no longer needed for nuclear weapons into mixed-oxide fuel made of a uranium-plutonium blend called MOX.

Obama’s 2015 budget would place the program to make mixed-oxide fuel, or MOX, on “cold standby” while officials continue to evaluate other ways to dispose of surplus plutonium.

“Following a year-long review of the plutonium disposition program, the budget provides funding to place the Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility in South Carolina into cold-standby,” the Office of Management and Budget said in the fiscal 2015 budget plan.

The OMB said the National Nuclear Security Administration “is evaluating alternative plutonium disposition technologies to MOX that will achieve a safe and secure solution more quickly and cost effectively.” The administration remains committed to safe disposition of plutonium under a nuclear nonproliferation agreement with Russia.

MOX can be used to fuel nuclear power plants. In fact, one of the stricken Japanese reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi plant used MOX fuel before the March 11, 2011 meltdown caused by and earthquake and resulting tsunami.

Reprocessing of commercial nuclear fuel to make MOX is done in the United Kingdom and France, and in Russia, India and Japan.

But the U.S. MOX program has experienced years of delays and is billions of dollars over budget. Following a year-long review of the MOX program, the Energy Department estimated it will cost $30 billion to complete. At least $5 billion has already been spent on construction of the 600,000-square-foot facility.

If built as planned, the facility would be capable of turning 3.5 metric tons of weapon-grade plutonium into MOX fuel assemblies annually. The facility would be licensed for 20 years, with operations to continue into the 2030s. But that plan is now in doubt.

“The MOX program has major problems,” said Edwin Lyman, a senior scientist in the Union of Concerned Scientists Global Security Program.

“The estimate for the MFFF’s construction cost, for example, has ballooned from $4.8 billion to $7.7 billion, and the total life cycle cost of the program is now estimated at $30 billion,” said Lyman.

“And even if the plant is built, no U.S. utility has committed to take the fuel, which is far more expensive and troublesome too use than conventional uranium fuel,” Lyman said. “As a result, the Energy Department is seriously reevaluating whether the program should go forward at all.”

In a report released in February, the Government Accountability Office, the investigative branch of Congress, audited the cost and schedule estimates of the contractor, Shaw Areva MOX Services, and concluded that it “did not meet all best practices in GAO’s guides for preparing high-quality, reliable cost and schedule estimates. Not meeting these best practices increased the risk of further cost estimates and delays for the projects…” the report states.

Even so, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Atomic Safety and Licensing Board in February rejected a challenge to the license granted to Shaw Areva MOX Services to operate the MOX facility at the Savannah River Site.

“Although we have not yet seen the details of the decision, which is not yet public, we are deeply disappointed and frustrated by this outcome,” said Lyman, speaking for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“After years of thorough scrutiny of the applicant’s plan for keeping track of the location and quantity of weapon-usable plutonium in this facility, we are convinced that the plan is deeply deficient and the applicant is simply incapable of securing and accounting for this incredibly dangerous material,” he warned.

“The decision to grant this facility an operating license, allowing it to take possession of at least 34 metric tons of U.S. surplus plutonium, is reckless and will increase the risk that terrorists will be able to acquire enough plutonium to build a nuclear bomb without detection,” warned Lyman.

Friends of the Earth’s Nuclear subsidies campaigner Katherine Fuchs commented, “Cold standby is a very fitting conclusion to the Department of Energy’s year-long review of the MOX program. The MOX program has been lagging behind schedule and shooting over budget for years. Congress should follow the President’s lead in redirecting funding to the search for faster, less expensive technologies to dispose of plutonium.”

The Tennessee Valley Authority had agreed to study the use of MOX fuel produced at the Savannah River plant as nuclear fuel at its Sequoyah and Browns Ferry nuclear plants, but backed off after the Fukushima meltdown.

Critics of the project praised the Obama Administration for winding down funding for the MOX facility.

“The MOX program is unsustainable due to run-away costs, and the shut-down of the project must be carried out quickly while the Department of Energy immediately initiates options to dispose of plutonium as waste,” said Tom Clements, adviser to the South Carolina Chapter of the Sierra Club. “This is only a [budget] request but if it goes through, MOX is dead.”

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2014. All rights reserved.

© 2014, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.