NORWICH, England, UK, December 12, 2025 (ENS) – As the planet heats up, a population of polar bears living in southeastern Greenland appear to be adjusting to their warmer environment, new research by scientists at the University of East Anglia, UEA, shows.

The study, “Diverging transposon activity among polar bear sub-populations inhabiting different climate zones,” published today in the journal “Mobile DNA,” reveals a link between rising temperatures and changes in polar bear DNA, which may be helping them adapt and survive even as the planet endured the hottest year since record-keeping began in 2024.

This study is believed to be the first time a statistically significant link has been found between rising temperatures and changing DNA in a wild mammal species.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is a set of instructions carried in the nucleus of each cell for creating the proteins that make the bodies of all living things function. Two strands of DNA together form a double helix, looking similar to a spiral staircase.

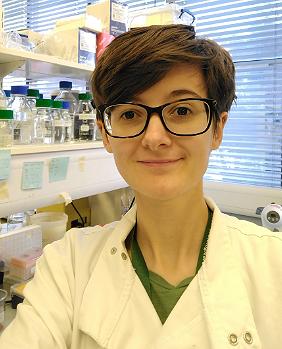

The University of East Anglia team – molecular biologist in reproduction and fertility Dr. Alice Godden, data scientist Dr. Benjamin Rix, and professor of genetics and reproduction Dr. Simone Immler – discovered that some genes related to heat stress, aging and metabolism are behaving differently in the polar bears living in southeastern Greenland.

Their finding suggests that these genes play a key role in how a range of polar bear populations are adapting or evolving in response to their changing local climates and diets.

The authors say understanding these genetic changes is important for guiding future conservation efforts and analysis, enabling us to see how polar bears might survive in a warming world and which populations are most at risk.

The new research comes as the Arctic is at its warmest with temperatures continuing to rise, reducing vital sea ice platforms that the bears use to hunt seals, leading to isolation and food scarcity for the bears.

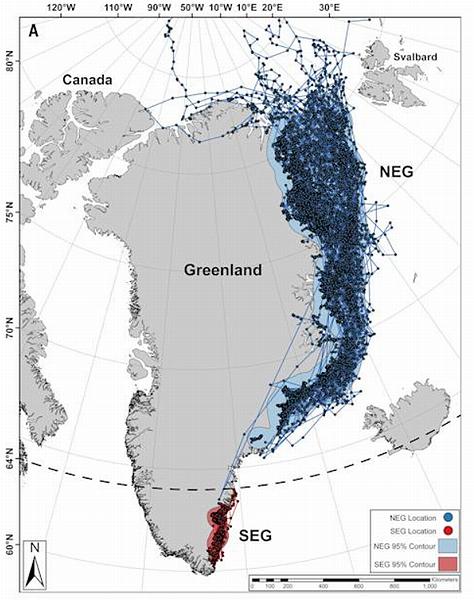

The study analyzed blood samples taken from polar bears in both northeastern and southeastern Greenland to compare the activity of so-called “jumping genes,” small, mobile pieces of the genome that can influence how other genes work.

Also called transposons, the jumping genes govern the bears’ relationship with temperatures in the two regions and associated changes in gene expression.

The UEA scientists found that temperatures in northeastern Greenland were colder and less variable, while in the southeast they fluctuated and it was a warmer environment. This less icy habitat is creating many challenges and changes for the resident bears, and it is similar to the future conditions predicted for the species.

Lead researcher Dr. Godden, from UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, cautioned that while the finding offers some “hope” for the polar bears, efforts to limit global temperature increases must continue.

“DNA is the instruction book inside every cell, guiding how an organism grows and develops,” Dr. Godden said. “By comparing these bears’ active genes to local climate data, we found that rising temperatures appear to be driving a dramatic increase in the activity of jumping genes within the southeastern Greenland bears’ DNA.

“Essentially this means that different groups of bears are having different sections of their DNA changed at different rates, and this activity seems linked to their specific environment and climate,” she explained.

“This finding is important because it shows, for the first time, that a unique group of polar bears in the warmest part of Greenland are using jumping genes to rapidly rewrite their own DNA, which might be a desperate survival mechanism against melting sea ice,” Dr. Godden speculated.

“As the rest of the species faces extinction,” she said, “these specific bears provide a genetic blueprint for how polar bears might be able to adapt quickly to climate change, making their unique genetic code a vital focus for conservation efforts.”

“However, we cannot be complacent, this offers some hope but does not mean that polar bears are at any less risk of extinction. We still need to be doing everything we can to reduce global carbon emissions and slow temperature increases,” Dr. Godden said.

Over time our DNA sequence can change and evolve, but environmental stress, such as warmer climates, can accelerate the process, she said.

Changes were also found in gene expression areas of DNA linked to fat processing, which the researchers say is important when food is scarce. It could mean the southeastern bears are slowly adapting to the rougher plant-based diets found in the warmer regions, compared to the mainly fatty, seal-based diets of the northern polar bear populations.

“We identified several genetic hotspots where these jumping genes were highly active, with some located in the protein-coding regions of the genome, suggesting that the bears are undergoing rapid, fundamental genetic changes as they adapt to their disappearing sea ice habitat,” Dr. Godden said.

The UEA research builds on a 2022 study by the University of Washington, which discovered that the southeastern population of Greenland polar bears was genetically different from the northeastern group, after the two groups of bears were separated about 200 years ago.

“We wanted to survey this region because we didn’t know much about the polar bears in Southeast Greenland, but we never expected to find a new subpopulation living there,” said lead author Dr. Kristin Laidre, a polar scientist at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory who studies the ecology and population dynamics of Arctic marine mammals, including the impacts of climate change.

“We knew there were some bears in the area from historical records and Indigenous knowledge. We just didn’t know how special they were,” Dr. Laidre said.

Dr. Laidre aims to understand and quantify the effects of sea ice loss on polar bears in all four sub-populations around Greenland – Kane Basin, Baffin Bay, Davis Strait and East Greenland – using longitudinal capture-recapture studies and tracking of individuals with satellite telemetry.

The previously unknown subpopulation of polar bears in Southeast Greenland survive with limited access to sea ice by hunting from freshwater ice that pours into the ocean from Greenland’s glaciers, she says.

Because this isolated population is genetically distinct and uniquely adapted to its environment, studying it could shed light on the future of the species in a warming Arctic.

The genetic difference between this group of bears and its nearest genetic neighbor is greater than that observed for any of the 19 previously known polar bear populations.

“They are the most genetically isolated population of polar bears anywhere on the planet,” said Dr. Laidre’s coauthor Dr. Beth Shapiro, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

“We know that this population has been living separately from other polar bear populations for at least several hundred years, and that their population size throughout this time has remained small,” Dr. Shapiro said.

The study, published June 17, 2022 in the journal “Science,” combines seven years of new data collected along the southeastern coast of Greenland with 30 years of historical data from the island’s whole east coast. The remote southeast region had been poorly studied because of its unpredictable weather, jagged mountains, and heavy snowfall. The newly collected genetics, movement, and population data show how these bears use glacier ice to survive with limited access to sea ice.

Dr. Godden and her colleagues analyzed genetic activity data collected for that study from 17 adult polar bears – 12 from northeastern and five from southeastern Greenland.

They used a technique called RNA sequencing to look at RNA expression, the molecules that act like messengers, showing which genes are active. This gave them a detailed picture of gene activity, including the behavior of jumping genes.

Their study was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and the European Research Council.

Dr. Godden said the next step will be to look at other polar bear populations. There are some 20 sub-populations around the world. She hopes “this work will highlight the urgent need to analyze the genomes of this precious and enigmatic species before it is too late.”

Featured image: Polar bear on an ice floe off the northeast coast of Greenland. (Photo by Mathane Qatsa, Visit East Greenland)

© 2025, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.