HOUSTON, Texas, October 4, 2021 (ENS) – A process to extract valuable metals from electronic waste that uses up to 500 times less energy than current lab methods and produces a byproduct clean enough for agricultural land has been developed at Rice University.

The flash Joule heating method introduced last year to produce graphene from carbon sources like waste food and plastic has been adapted to recover rhodium, palladium, gold and silver from discarded electronics for reuse.

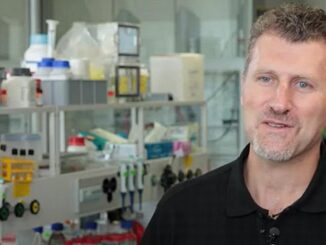

A new report in the journal “Nature Communications” by the Rice University lab of chemistry professor James Tour shows how highly toxic heavy metals such as chromium, arsenic, cadmium, mercury and lead are removed from the flashed materials, leaving a byproduct with minimal metal content.

“We found a way to get the precious metals back and turn e-waste into a sustainable resource,” Tour said. “The toxic metals can be removed to spare the environment,” said Dr. Tour, who is a professor of computer science and also of materials science and nanoengineering, as well as a professor of chemistry at Rice.

Tour said that with more than 40 million tons of e-waste produced globally every year, there is plenty of potential for urban mining.

“Here, the largest growing source of waste becomes a treasure,” Tour said. “This will curtail the need to go all over the world to mine from ores in remote and dangerous places, stripping the Earth’s surface and using gobs of water resources. The treasure is in our dumpsters.”

He said an increasingly rapid turnover of personal devices like cell phones has driven the worldwide rise of electronic waste, with only about 20 percent of landfill waste currently being recycled.

“Precious metal recovery from electronic waste, termed urban mining, is important for a circular economy,” the Tour report explains.

“Present methods for urban mining, mainly smelting and leaching, suffer from lengthy purification processes and negative environmental impacts. Here,” the report states, “a solvent-free and sustainable process by flash Joule heating is disclosed to recover precious metals and remove hazardous heavy metals in electronic waste within one second.”

Flash Joule Heating Delivers a Jolt

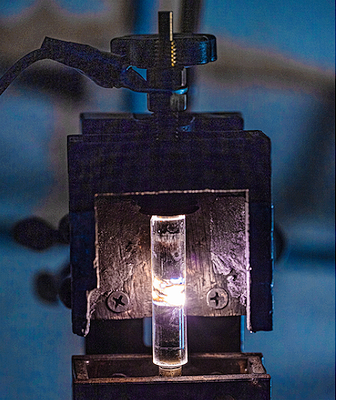

Instantly heating the waste to 3,400 Kelvin (5,660 degrees Fahrenheit) with a jolt of electricity vaporizes the precious metals, and the gases are vented away for separation, storage or disposal.

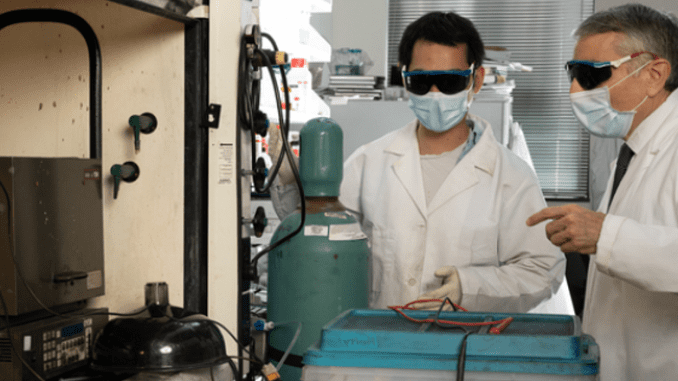

The lab found flashing e-waste requires some preparation. Guided by lead author and Rice postdoctoral research associate Bing Deng, the researchers powdered circuit boards they used to test the process and added halides, like Teflon or table salt, and a dash of carbon black to improve the recovery yield.

Once flashed, the process relies on “evaporative separation” of the metal vapors. The vapors are transported from the flash chamber under vacuum to another vessel, a cold trap, where they condense into their constituent metals.

“The reclaimed metal mixtures in the trap can be further purified to individual metals by well-established refining methods,” Deng said.

The researchers reported that one flash Joule reaction reduced the concentration of lead in the remaining charred material to below 0.05 parts per million, the level deemed safe for agricultural soils.

Levels of arsenic, mercury and chromium were all further reduced by increasing the number of flashes.

“Since each flash takes less than a second, this is easy to do,” Tour said.

The scalable Rice process consumes about 939 kilowatt-hours of electricity per ton of material processed, 80 times less energy than commercial smelting furnaces and 500 times less than laboratory tube furnaces, according to the researchers.

Flash Joule heating also eliminates the lengthy purification required by smelting and leaching processes.

Co-authors of the paper are Rice alumnus Duy Xuan Luong, graduate students Zhe Wang and Emily McHugh and research scientist Carter Kittrell. The U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Department of Energy supported the research.

Featured image: Rice University chemist James Tour, left, and postdoctoral research associate Bing Deng prepare to flash electronic waste to recover its valuable metals for recycling. 2021 (Photo by Jeff Fitlow courtesy Rice University)

© 2021, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.