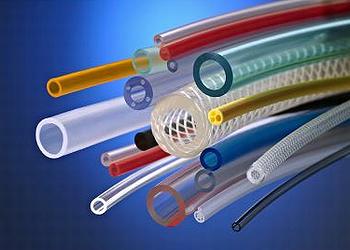

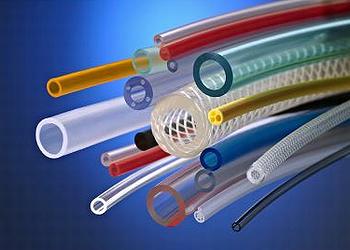

CHAMPAIGN, Illinois, February 7, 2019 (ENS) – A phthalate found in many plastic and personal care products may decrease fertility in female mice, new research has found. Phthalates are used as plasticizers, substances added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, durability, and longevity. They are used primarily to soften polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Researchers at the University of Illinois found that giving female mice oral doses of the phthalate DiNP for 10 days disrupted their reproductive cycles, decreasing their ability to become pregnant for up to nine months afterward.

DINP, formally known as Diisononyl phthalate, is used to soften vinyl.

The findings, reported recently in the journal “Toxicological Sciences,” add to a growing body of research that links phthalates, also called plasticizers, with various reproductive abnormalities and other health problems in rodents.

Phthalates are found in many types of consumer goods, such as food and beverage packaging, vinyl flooring, medical devices and cosmetics.

Research studies have reported a variety of health risks associated with the phthalates that the mice in the study consumed, DiNP and DEHP.

DEHP, or di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, is the most common member of the class of phthalates. Used as a plasticizer, this colorless viscous liquid is soluble in oil, but not in water.

In the last few years, government agencies and expert panels in Europe, the US, Canada, and Japan have reviewed the safety of DEHP, used to soften PVC medical devices. Each of these agencies and expert panels has found that DEHP exposure from some medical procedures may pose a risk to patients’ health.

In the EU, DEHP is classified as a reproductive toxicant.

The studies on these phthalates include a 2015 study in mice by University of Illinois scientist Jodi Flaws’ research group, which found that DEHP disrupted hormone signaling and the growth and functioning of the ovaries. That study was published in the journal “Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology.”

However, much of the previous research on phthalates used very high dosages that don’t reflect real-world exposure levels and the potential effects on female reproduction, said graduate student Katie Chiang, a co-author of the current study with Flaws.

To investigate these phthalates’ effects on female fertility, female mice were fed corn oil solutions containing environmentally relevant concentrations of DEHP or DiNP ranging from 20 micrograms to 200 milligrams per kilogram of body weight.

Such doses are comparable to the levels of exposure that people may experience during their daily living and work activities, Chiang said.

After the 10-day dosing period ended, the phthalate-treated female mice and their counterparts in the control group were paired with untreated male partners twice for breeding.

“At three months post-dosing, a third of the females that were treated with the lowest doses of DEHP and DiNP were unable to conceive after mating, while 95 percent of the females in the control group became pregnant,” Chiang said.

“The thing that was really concerning was that these females’ fertility was impaired long after their exposure to the chemicals stopped,” said Flaws, a professor of comparative biosciences at University of Illinois.

As in Flaws’ 2015 study, the findings suggested that steroid hormone production and signaling were disrupted. At three months and nine months post-dosing, the DiNP-treated females’ estrous cycles differed from those of the control group.

Examining the mice immediately after the 10-day dosing period, the researchers found that the treated females’ uteruses weighed less than those of the females in the control group, and their fertility patterns were different, too.

However, they found no such differences at the three-month and nine-month intervals.

Among the females treated with the lowest doses of DEHP or DiNP, there was a reduction in the number that became pregnant and produced pups compared with the control group.

Chiang and Flaws hypothesized that dysregulation of the mice’s steroidal hormones made their uterine linings less receptive to embryo implantation. There’s a narrow window of time when the endometrial lining of the uterus is receptive to implantation and a female’s sex steroid hormones must be well regulated for it to occur, according to the study.

Or, perhaps phthalate exposure accelerated the end of the female mice’s reproductive lifespans, reducing their chances of becoming pregnant, the researchers said. Other studies have reported that phthalate exposure in humans through cosmetics and personal care products can trigger reproductive aging, causing women to enter menopause several years early.

While the findings of the University of Illinois study have yet to be replicated in humans, Chiang and Flaws said they warrant further investigation, particularly into DEHP’s and DiNP’s potential effects on the ovaries and the production of sex steroid hormones.

“These chemicals’ half-lives in the body are relatively short,” Flaws said. “They tend to be broken down quickly and the metabolites excreted in urine within a couple of days. It’s troubling that these effects were continuing several months later.”

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and a Billie Field Fellowship.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2019. All rights reserved.

© 2019, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.