PORTLAND, Oregon, December 31, 2023 (ENS) – People who eat fish that live year-round in Oregon’s Lower Willamette River are taking a big risk, as these fish contain levels of toxic polychlorinated biphenyls high enough to harm health, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been warning for decades.

In November, the Justice Department added two settlements in federal court reflecting agreements among Tribal, state and federal natural resource trustees and over 20 potentially responsible parties, PRPs, to clean up what is now the Portland Harbor Superfund Site, designated in the year 2000. Past settlement agreements are online here.

The Portland Harbor Superfund site reached a key milestone on January 6, 2017 when the Environmental Protection Agency released its Record of Decision, the final plan for cleanup.

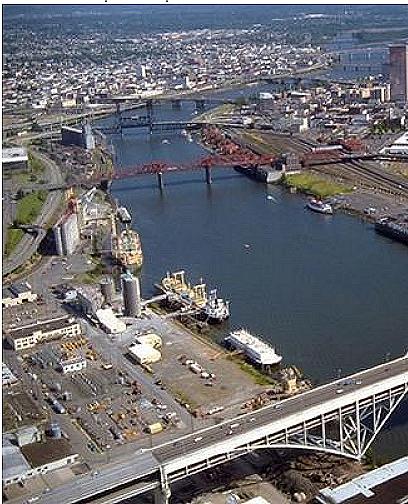

The Portland Harbor Superfund site is a 10-mile stretch of the lower Willamette River between the Broadway Bridge and the southern tip of Sauvie Island.

Approximately 150 parties are considered potentially responsible for the contamination, including some of the largest corporations in the United States, even one – Schnitzer Steel Industries, Inc. now doing business as Radius Recycling – that has been recognized for its environmental and climate action work.

One of the 150 potentially responsible parties is Schnitzer Steel Industries, which this year rebranded as Radius Recycling, in the business of buying and selling recycled metals around the world. In November, TIME magazine named the company to the inaugural TIME100 Climate List, which aims to recognize 100 innovative leaders working to expedite climate action. Earlier this year, Radius was named the Most Sustainable Company in the World by Corporate Knights and included on TIME’s List of the 100 Most Influential Companies of 2023.

Other polluters named in the Portland Harbor Superfund site cleanup agreements already filed in court are:

- – Daimler Trucks North America;

- – Vigor Industrial, the largest ship repair and modernization operation in the region;

- – Cascade General, which owns and operates Portland Shipyard;

- – NW Natural, a natural gas distributor;

- – Arkema Inc., a chemical manufacturer based near Paris, France;

- – Bayer Crop Science Inc., a German multinational corporation which produces herbicides, and insecticides that the 2020 EPA Administrative Settlement court documents linked to “cancer risks and noncancer health hazards from exposures to a set of chemicals in sediments, surface water, groundwater seeps, and fish tissue from samples collected at the Site.”

- – General Electric Company, a New York company that has polluted surface water, groundwater, sediment, and fish tissue with 64 contaminants of concern, including PCBs, PAHs, dioxins and furans, as well as DDT and its metabolites DDD and DDE (collectively, DDX);

- – oil companies Chevron U.S.A. Inc., Kinder Morgan Liquids Terminals LLC, McCall Oil and Chemical Corporation, Phillips 66 Company, and Shell Oil Company, Company, BP Products North America Inc., and ExxonMobil Corporation;

- – towboating and barging company Brix Maritime

- – Union Pacific Railroad Company

- – FMC Corporation, an American herbicide and fungicide manufacturer based in Pennsylvania

The settlement agreements, with an estimated restoration value of $33.2 million, require the potentially responsible parties to pay cash damages or purchase credits in projects to restore salmon and other natural resources that were lost due to contamination released from their facilities into the Willamette River.

This settlement includes more than $600,000 in damages for the public’s lost recreational use of the river, and restoration and monitoring of culturally significant plants and animals.

The settlement includes additional funds to cover costs paid by the Portland Harbor Natural Resource Trustee Council for assessing the harm to the injured natural resources.

The Trustee Council is made up of representatives from the Five Tribes: the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, and the Nez Perce Tribe, along with representatives of the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the State of Oregon.

“This settlement represents years of hard work by the Portland Harbor natural resource trustees and responsible parties who cooperated to restore the harm caused by those parties’ contamination. The resulting restoration projects funded by these agreements will provide permanent ecological benefits to help restore the biodiversity of the Willamette River system,” said Assistant Attorney General Todd Kim of the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division.

The Five Tribes “wholly support this settlement” the Tribes said in a statement. “Contamination has uniquely affected tribal members because of their cultural use of and relationship with affected natural resources in and around the Portland Harbor Superfund Site. The Five Tribes believe the collaborative process of this settlement represents the best path forward for restoring Portland Harbor natural resources for the benefit of both current and future generations.”

“The trustees are very pleased that the responsible parties in this settlement have advanced restoration over litigation. The large-scale restoration projects facilitated by this settlement will help address the most important habitat needs of fish and wildlife injured by contamination in Portland Harbor,” said Director Curt Melcher of Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“We will continue our settlement discussions with the remaining responsible parties who are participating in the early settlement initiative so we can achieve additional permanent restoration of natural resources,” Melcher said. “Partnering with restoration project developers has already produced on-the-ground restoration even prior to today’s settlement.”

Restoration Credits, a Novelty With Benefits

The use of restoration credits in four natural resource projects created in partnership with private developers is a novel and critical feature of the settlement, the Justice Department said.

Restoration credits are like ecological “shares” in a restoration project, and the natural resource trustees decide how many “shares” each project is worth. Defendants in the settlement can purchase restoration credits from the restoration project developers instead of paying cash to resolve the ecological injury portion of their liability.

Using this approach at Portland Harbor has produced on-the-ground restoration sooner and at less cost than traditional cash-only settlements.

The four restoration projects selling restoration credits – Alder Creek, Harborton, Linnton Mill and Rinearson Natural Area – provide habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon listed under the Endangered Species Act, and they are of cultural significance to the Five Tribes.

The projects will restore habitat for other fish and wildlife injured by contamination in Portland Harbor, species such as bald eagles, mink and lamprey, as well as tribally significant native plants like camas, wapato and sweetgrass.

“Cleaning up and restoring the Portland Harbor is important for all Oregonians, but it will also be one small step towards righting the many injustices done to the Nez Perce Tribe,” said Courtney Johnson, executive director and staff attorney with the Portland-based Crag Law Center.

Construction is complete and habitat development is underway at all four projects, which are expected to provide ecological benefits in perpetuity, will be permanently protected from development and will receive long-term stewardship.

Collectively, the restoration value in these projects is the largest natural resource credit bank at any Superfund Site in the country, the EPA explains.

The agreements result from an early settlement collaboration between the natural resource trustees at the Portland Harbor Superfund Site and a group of PRPs who participated in that effort.

Negotiations are continuing with other PRPs that also are participating in the trustees’ early settlement initiative. If the trustees reach agreements in those ongoing negotiations, they could include additional cash settlements or restoration credit purchases in the four restoration projects.

On behalf of the trustees on the Trustee Council, the U.S. Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division’s Environmental Enforcement Section filed the complaint and lodged the proposed consent decrees in the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon.

The proposed decrees resolve the natural resource damages allegations of the United States, Oregon and the Five Tribes for releases of contamination from the PRPs’ identified facilities. Alleged violations are of Section 107 of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act; the Oil Pollution Act and the Clean Water Act.

The Superfund site is located along the lower reach of the Willamette River in Portland, and extends from river mile 1.9 to 11.8. While the site is industrialized, it is within a region where commercial, residential, recreational, and agricultural uses exist. The site includes marine terminals, manufacturing, other commercial operations, public facilities, parks, and open spaces.

This lower reach was once a shallow, meandering portion of the Willamette River but has been redirected and channelized with filling and dredging. A federally maintained navigation channel, extending nearly bank-to-bank in some areas, doubles the natural depth of the river and allows transit of large ships into the harbor. Along the river bank are overwater piers and berths, port terminals and slips, and other engineered features.

Invertebrates, fishes, birds, amphibians, and mammals, including some protected by the Endangered Species Act, use habitats within and along the river. The river is also an important rearing site and pathway for migration of salmon and lamprey. Recreational fisheries for salmon, bass, sturgeon, crayfish, among others, are still active within the lower Willamette River.

The greatest risk to humans is connected to eating the fish that live there year-round, like bass and carp. Salmon and fish that pass through the river to the ocean are safe to eat, the EPA advises

Seawalls are used to control periodic flooding as most of the original wetlands bordering the Willamette in the Portland Harbor area have been filled. Some river bank areas and adjacent parcels have been abandoned and allowed to revegetate, and beaches have formed along some modified shorelines due to natural processes.

The settlement is subject to a 45-day public comment period and final court approval. It is available for viewing here. Please refer to the upcoming Federal Register notice for instructions on submitting any public comments on the settlement. More information is available on the Portland Harbor Natural Resource Trustee Council website.

Featured image: A view of the Portland Harbor Superfund site with Mount Hood, Oregon’s tallest mountain at 11,249 feet, in the background. (Photo courtesy U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

© 2023, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.