COPENHAGEN, Denmark, May 20, 2024 (ENS) – Long-term exposure to air pollution leads to increased dementia risk, new research from the University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Health and Medial Sciences suggests.

The study, titled “Long-term exposure to air pollution and road traffic noise and incidence of dementia in the Danish Nurse Cohort,” followed a group of nurses for 27 years, from 1993 until 2020.

Of 25,233 nurses studied, 1,409 developed dementia. Particulate matter with a diameter of ≤2.5 µm (PM2.5) was associated with dementia incidence, after adjusting for lifestyle, socioeconomic status, and road traffic noise.

Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution is associated with asthma onset in children and adults, lower respiratory infection in children, and premature death – these facts have been known for years. But the link between polluted air and dementia is just now becoming apparent.

Breathing particulate matter – the term for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air – can lead to dementia. Some particles, such as dust, dirt, soot, or smoke, are large or dark enough to be seen with the naked eye. But others are so small they can only be detected using an electron microscope.

PM2.5 – fine inhalable particles, with diameters that are 2.5 micrometers and smaller, are minuscule. You could line up 30 of these particles across the diameter of one human hair.

Published in the May 8 issue of the journal “Alzheimer’s and Dementia,” the research shows that air pollution promotes inflammation in the brain, hastening mental decline and increasing the risk of dementia.

“We also find association with noise, but this seems to be explained by air pollution primarily. Our study is in line with growing international knowledge on this topic,” said Professor Zorana Jovanovic Andersen, a specialist in environmental epidemiology at the Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen.

“This is the first study in Denmark showing a link between air pollution and dementia,” said Andersen, who also chairs the European Respiratory Society Environment and Health Committee.

“Although air pollution levels in Denmark have been declining and are relatively low, compared of the rest of Europe and world, this study shows that there are still significant and concerning health effects that demand more action and policies towards reduction of air pollution,” she explained.

“As we are going to live longer, and more and more people will be diagnosed with dementia, this finding is important as it offer an opportunity to prevent new dementia cases, and ensure more healthy aging, by cleaning up the air we breathe,” Andersen said.

Beyond air pollution’s well-known effects on respiratory and cardiovascular systems, breathing polluted air also has major impacts on our brains, promoting inflammation, and increasing risk of dementia.

Stéphane Tuffier, a medical doctor in public health who worked on this study as an environmental health research assistant at the University of Copenhagen, said the research was and still is “internationally unique and necessary.”

“This is internationally unique and necessary in regards of the development of dementia which can take many years,” Dr. Tuffier said.

“Second, the air pollution was estimated for each participant for a total of 41 years – from 1979 until 2020 – which is also incredible.

Third, we had extensive details about participants’ lifestyles and socio-economics and all our results take them in consideration. The novelty of this study is the very detailed and accurate data that we used,” Dr. Tuffier said.

He made the point that physical exercise is also important in fighting off dementia.

“Nurses with higher physical activity had a lower risk of dementia when exposed to air pollution compared to nurses with less physical activity,” Dr. Tuffier said. “This indicates that physical activity might mitigate the adverse effects of air pollution on cognitive decline and risk of dementia.”

In the United States, a smaller study came up with similar results.

A study by researchers at Duke and Columbia universities finds older, non-white adults are more likely to live in areas with higher air pollution and near toxic disposal sites, among environmental injustices, potentially undermining their cognitive health.

Published May 14 in the “Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports,” the study of 107 older adults found that non-white New York and North Carolina residents with mild cognitive impairment reside in places with more environmental injustices than their white peers.

“A lot of money has been spent on understanding the genetics and pathological characterization of Alzheimer’s disease. But we still don’t have a good way to quantify the dozens of environmental risks for the disease and how they may interact together,” said P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, FRCP, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University’s School of Medicine, and senior author of the study.

The results add to a growing area of research exploring the connections between environmental factors and brain health, racial injustices, and aging, and suggests looking at a patient’s address may be just as important for care providers to consider as listening to their heart or ordering a brain scan.

“An all-encompassing snapshot tying multiple environmental factors and resources available based on where someone lives to neurodegenerative disorders, like Alzheimer’s disease, has not been explored as well,” said Alisa Adhikari, a clinical research associate in Dr. Doraiswamy’s lab and the study’s first author.

Race and Place on the Mind

107 participants aged 55 – 95 with mild cognitive impairment living in or around New York City or Durham, North Carolina were recruited to study the effectiveness of computerized cognitive training therapies, such as crossword puzzles and brain games, on slowing dementia progression over 78 weeks.

To get a fuller sense of how place, race, and the mind influence each other, co-author Adaora Nwosu pulled in data from the Center for Disease Control’s Environmental Justice Index (EJI). The EJI provides location-specific information about 36 environmental and social burden indicators such as neighborhood walkability and access to green spaces, diesel exhaust, air, water and noise pollution levels, as well as the likelihood of living in older homes with greater exposure to lead or asbestos.

Non-white participants, mainly Black enrollees, were found to face higher environmental burdens.

“Minorities had greater exposure to ozone, diesel, particulate matter, carcinogenic air toxins, lack of recreation of parks, and proximity to toxic disposal sites,” Adhikari said, which she says explains, in part, the higher environmental burden scores.

Older non-white adults also scored much worse on social vulnerability metrics, such as more likely to live in older homes within poorer neighborhoods, which the authors suggest may be a result of past injustices.

There were no connections found, however, between race, location, and measures of cognitive decline likely due to all participants actively taking medicine and doing brain training exercises to curb neurological symptoms, as part of the study’s original research design.

Analysis of the EJI data also revealed that adults from the New York City site tended to live in areas with markedly higher pollution compared to counterparts in Durham, which may have impacted or accelerated their decline even before enrolling in treatment.

“This was eye-opening for us,” Dr. Doraiswamy said. “We tend to treat all sites and all subjects in a clinical trial as homogeneous with regards to environmental exposures. Moving forward, this type of metric may prove useful to help us better study how environmental exposures impact clinical trial outcomes.”

ZIP Codes as Part of a Checkup

Dr. Doraiswamy described the findings as a “pilot study,” and as such, his team is now planning for a larger, national study with thousands of participants that includes more objective neurodegeneration measurements like MRI brain scans to better assess cognitive health over time.

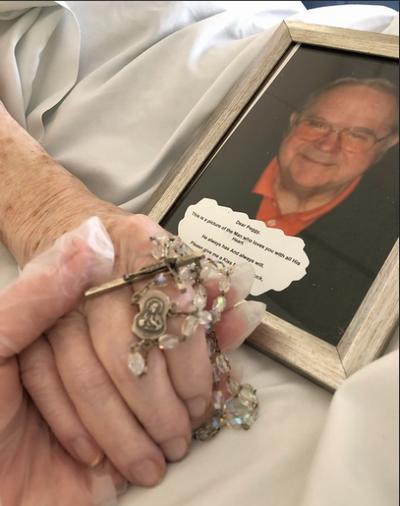

Featured image: Nurses in the Danish cohort studied in this research. University of Copenhagen, March 2017 (Photo courtesy European Trade Union Institute)

© 2024, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.