TOWNSVILLE, Queensland, Australia, April 13, 2019 (ENS) – The damage caused to the Great Barrier Reef by the warming climate has compromised the capacity of its corals to recover, finds new research published earlier this month in the journal “Nature.”

The unique study measured how many adult corals survived along the length of the world’s largest reef system following extreme heat stress, and how many new corals they produced to replenish the Great Barrier Reef in 2018.

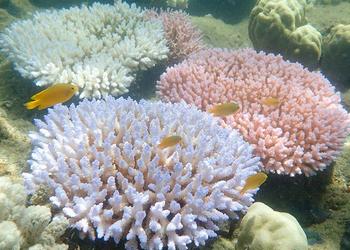

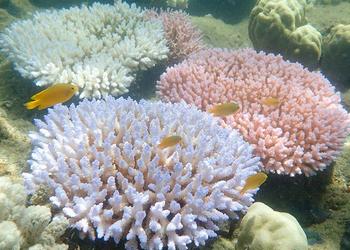

The loss of adults resulted in a crash in coral replenishment compared to levels measured in the years before mass coral bleaching.

“Dead corals don’t make babies,” said lead author Professor Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University. “The number of new corals settling on the Great Barrier Reef declined by 89 percent following the unprecedented loss of adult corals from global warming in 2016 and 2017.”

To date, the Great Barrier Reef has experienced four mass bleaching events due to global warming, in 1998, 2002, and back-to-back in 2016 and 2017. Scientists predict that the gap between pairs of coral bleaching events will continue to shrink as global warming intensifies.

“The number of coral larvae that are produced each year, and where they travel to before settling on a reef, are vital components of the resilience of the Great Barrier Reef. Our study shows that reef resilience is now severely compromised by global warming,” said co-author Professor Andrew Baird.

“The biggest decline in replenishment, a 93 percent drop compared to previous years, occurred in the dominant branching and table coral, Acropora. As adults these corals provide most of the three-dimensional coral habitat that support thousands of other species,” he said.

“The mix of baby coral species has shifted, and that in turn will affect the future mix of adults, as a slower than normal recovery unfolds over the next decade or longer,” said Baird.

“The decline in coral recruitment matches the extent of mortality of the adult broodstock in different parts of the Reef,” said Hughes. “Areas that lost the most corals had the greatest declines in replenishment.”

“We expect coral recruitment will gradually recover over the next five to 10 years, as surviving corals grow and more of them reach sexual maturity, assuming of course that we don’t see another mass bleaching event in the coming decade,” he said.

“It’s highly unlikely that we could escape a fifth or sixth event in the coming decade,” said co-author Professor Morgan Pratchett. “We used to think that the Great Barrier Reef was too big to fail – until now.”

“For example, when one part was damaged by a cyclone, the surrounding reefs provided the larvae for recovery. But now, the scale of severe damage from heat extremes in 2016 and 2017 was nearly 1,500 kilometers, vastly larger than a cyclone track.”

Professor Pratchett said the southern reefs that escaped the bleaching are still in very good condition, but they are too far away to replenish reefs further north.

“There’s only one way to fix this problem,” says Hughes, “and that’s to tackle the root cause of global heating by reducing net greenhouse gas emissions to zero as quickly as possible.”

Flooding Dumps Contaminated Water on the Reef

The world’s largest reef faces other issues, too. Recent north Queensland flooding and the mass outflows of polluted water onto the Great Barrier Reef have focused attention on the impact of water quality on the reef’s health.

But new research from the ARC Centre of Excellence reveals that even if water quality is improved, that alone won’t be enough to save the Great Barrier Reef.

Flooded Queensland rivers have dumped millions of liters of polluted water onto the reef, but until now the impact of these events on reef corals and marine life has been tough to assess.

Using a combination of advanced satellite imaging and over 20 years of coral monitoring across the reef, a team of researchers from ARC Centre of Excellence, the University of Adelaide, and Canada’s Dalhousie University has found that chronic exposure to poor water quality is limiting the recovery rates of corals across wide swathes of the Great Barrier Reef.

“We found the Great Barrier Reef is an ecosystem dominated by runoff pollution, which has greatly reduced the resilience of corals to multiple disturbances, particularly among inshore areas,” said lead author Dr. Aaron MacNeil of Dalhousie University.

“These effects far outweigh other chronic disturbances, such as fishing, and exacerbate the damage done by crown-of-thorns starfish and coral disease,” MacNeil said.

Poor water quality reduced the rates at which corals recover after disturbances by up to 25 percent, said MacNeil, who believes that by improving water quality, the rates of reef recovery can be enhanced.

The findings provide strong support for government policies aimed at reducing nutrient pollution to help increase the resilience of the Great Barrier Reef, in recovering from damage due to tropical cyclones, crown-of-thorns outbreaks and coral bleaching.

Stopping Runoff Good, But Not Enough

Yet the effects of water quality only go so far. Using a series of scenarios modeling future changes in climate and the likelihood of coral bleaching, the team found that no level of water quality improvement was able to maintain current levels of coral cover among the most scenic and valuable outer-shelf reefs that sustain much of the reef tourism industry.

Dr. Camille Mellin of the University of Adelaide said, “Coral reefs, including the Great Barrier Reef, are subject to an increasing frequency of major coral die-off events associated with climate change driven by coral bleaching. With these increasingly common disturbances becoming the new normal, the rate of coral recovery between disturbances has become incredibly important.”

While the effects of improved water quality on recovery rates of inshore reefs were encouraging, Dr. Mellin said, “No level of water quality improvement will be sufficient to ensure maintenance of the clear water reefs on the outer shelf, the very reefs that tourists come to Australia to see.”

“What these results emphasize is that there is no silver bullet for addressing the threats facing the Great Barrier Reef,” said Dr. MacNeil.

“Clearly reducing pollution in river runoff can have widespread, beneficial effects on reef corals and should continue to be supported. But for areas of the reef not impacted by water quality, our emphasis must be on mitigating carbon emissions to slow down climate change,” he said.

“We must give our reefs the time and conditions to recover,” MacNeil said. “Without that, the most stunning and iconic parts of the reef will soon decline and be unrecognizable from their current form.”

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2019. All rights reserved.

© 2019, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.