GREENBELT, Maryland, August 29, 2013 (ENS) – Using ice-penetrating radar, scientists have discovered a long, deep canyon that exists a mile beneath the Greenland ice sheet, data from a NASA airborne science mission and an international research team reveals.

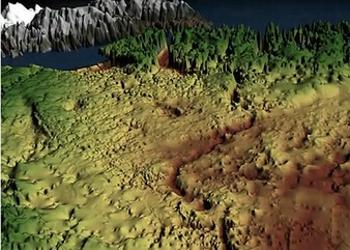

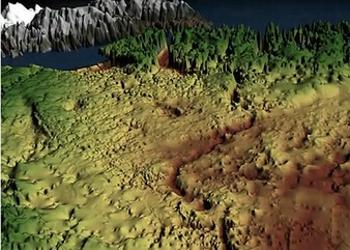

The scientific team identified a continuous bedrock canyon that extends from almost the center of the island and ends at its northern extremity in a deep fjord connecting to the Arctic ocean.

The canyon looks like a winding river channel at least 460 miles (750 kilometers) long, making it longer than the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in the United States. In some places, it is half a mile deep, on the same scale as parts of the Grand Canyon.

Scientists say this immense feature beneath the Petermann Glacier fjord is even older than the ice sheet that has covered Greenland for the last few million years.

“One might assume that the landscape of the Earth has been fully explored and mapped,” said Jonathan Bamber, professor of physical geography at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, and lead author of the study.

“With Google Streetview available for many cities around the world and digital maps for everything from population density to happiness one might assume that the landscape of the Earth has been fully explored and mapped,” said Bamber. “Our research shows there’s still a lot left to discover.”

Bamber and his team published their findings Thursday in the journal “Science.”

The scientists used thousands of miles of airborne radar data, collected by NASA and researchers from the United Kingdom and Germany over decades, to piece together the landscape lying beneath the Greenland ice sheet.

Much of this data was collected from 2009 through 2012 by NASA’s Operation IceBridge, an airborne science campaign that studies polar ice. One of IceBridge’s scientific instruments, the Multichannel Coherent Radar Depth Sounder, can see through vast layers of ice to measure its thickness and the shape of bedrock below.

At certain frequencies, radio waves can travel through the ice and bounce off the bedrock underneath. The amount of time the radio waves took to bounce back helped researchers determine the depth of the canyon. The longer it took, the deeper the bedrock feature.

“Two things helped lead to this discovery,” said Michael Studinger, IceBridge project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “It was the enormous amount of data collected by IceBridge and the work of combining it with other datasets into a Greenland-wide compilation of all existing data that makes this feature appear in front of our eyes.”

The researchers believe the canyon plays an important role in transporting sub-glacial meltwater from the interior of Greenland to the edge of the ice sheet and on into the ocean.

Evidence suggests that before the presence of the ice sheet, as much as four million years ago, water flowed in the canyon from the interior to the coast and was a major river system.

“It is quite remarkable that a channel the size of the Grand Canyon is discovered in the 21st century below the Greenland ice sheet,” said Studinger. “It shows how little we still know about the bedrock below large continental ice sheets.”

The research was funded by a European Union program called ice2sea and the UK Natural Environment Research Council.

Said Professor David Vaughan, ice2sea co-ordinator based at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge, England, “A discovery of this nature shows that the Earth has not yet given up all its secrets. A 750km canyon preserved under the ice for millions of years is a breathtaking find in itself, but this research is also important in furthering our understanding of Greenland’s past.”

“This area’s ice sheet contributes to sea level rise and this work can help us put current changes in context,” said Vaughan.

The IceBridge scientists will return to Greenland in March 2014 to continue collecting data on land and sea ice in the Arctic using a suite of instruments that includes ice-penetrating radar.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2013. All rights reserved.

© 2013, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.