OTTAWA, Ontario, Canada, April 2, 2013 (ENS) – The Government of Canada is quietly withdrawing from the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, UNCCD, the only legally binding international treaty that addresses desertification, land degradation and drought.

The decision of Stephen Harper’s Conservative Government, which is still unannounced on the government’s website, makes Canada the only country in the world outside the agreement.

The federal cabinet last week ordered the withdrawal on the recommendation of Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird, ahead of a major scientific meeting on the convention this month in Bonn, Germany, where the UNCCD’s secretariat is headquartered.

The UNCCD secretariat and the office of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon were informed of Canada’s decision to withdraw from the convention on March 28.

Canada signed the convention in 1994 and ratified it in 1995.

Canada’s withdrawal comes just as a high-level meeting of governments and scientists concluded in March that proactive drought management planning is now possible due to major advances in science and technology, and new knowledge about sustainable land management.

“The Convention is stronger than ever before, which makes Canada’s decision to withdraw from the Convention all the more regrettable,” the UNCCD secretariat said in a statement Friday.

“The UNCCD and its institutions works with all stakeholders and will continue to do so to safeguard the key resource base for food, water and energy security, and to sharply reduce poverty and build the resilience of rural ecosystems to expected climatic shocks like droughts,” the UNCCD secretariat said.

The UNCCD thanked the Government of Canada and Canadian civil society for playing “significant roles in moving the Convention to where it is today.”

It also noted Canada’s annual contribution of about 3.127 percent of the current Convention’s budget, or C$290,644 in 2011.

Yet a spokesman for Canada’s International Co-operation Minister Julian Fantino said in an email to the “Globe & Mail” newspaper, “Membership in this convention was costly for Canadians and showed few results, if any for the environment.”

The UNCCD secretariat praised Canada for being a “major actor in global efforts to address food security in developing countries” while also being “frequently subjected to drought” with 60 percent of its cropland in dry areas.

“We believe Canada will seize every opportunity to support efforts to sustain the implementation of the Convention for the good of present and future generations,” the UNCCD said.

NDP foreign affairs critic Paul Dewar said the decision shows that “the government is clearly outside of what is international norms here. We’re increasing our isolation by doing this.”

Ian Hanington, communications manager with the Vancouver-based nonprofit David Suzuki Foundation, said Canada is becoming “increasingly isolated on the world stage, especially when it comes to environmental issues – from pulling out of the Kyoto Accord to shutting down world-renowned research facilities like the Experimental Lakes Area to this latest move.”

Last year, Canada abandoned the Kyoto Protocol, a UN treaty that limits emissions of six greenhouse gases responsible for climate change.

The Experimental Lakes Area is an internationally unique research station based on whole-ecosystem experiments that address key issues in water management. The ELA has influenced public policy in water management in Canada, the United States and Europe.

But the Harper Government discontinued financial support to the Experimental Lakes Area at the end of the financial year, March 31, 2013. The site, encompassing 58 formerly pristine freshwater lakes in Ontario’s Kenora District will be either decommissioned or handed to a third-party operator.

The 2012 budget bill (Bill C-38) passed last June weakened Canada’s environmental laws and silenced Canadians who want to defend them. The changes amount to an entirely new, and less comprehensive, environmental assessment law, broad decision-making powers for Cabinet and ministers, and less accountability and fewer opportunities for public participation.

Hanington said, “With continued cutbacks and attacks on scientific and environmental programs, resources and organizations, one has to wonder whose interests the government is representing. If the government is abdicating its responsibilities on the environment to the provinces and industry, who will speak for us internationally?”

“For our government to stop working with the rest of the world to resolve some of the most serious issues we face is a betrayal of Canadian values,” said Hanington.

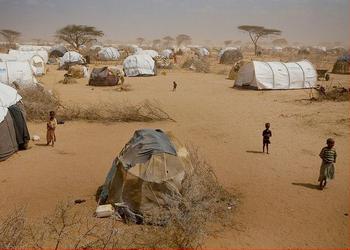

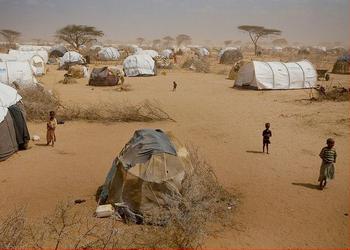

The UNCCD estimates that droughts are the world’s costliest natural disaster, accounting for up to US$8 billion annually, and impacting more people than any other form of natural disaster.

The frequency, intensity, and duration of droughts are expected to rise as a result of climate change, with an increasing human and economic toll, the UNCCD says.

Since the 1970s, the land area affected by drought has doubled, undermining livelihoods, reversing development gains and entrenching poverty among millions of people who depend directly on the land.

Yet there is hope. In March, the High-level Meeting on National Drought Policy made the first globally-coordinated attempt to move towards science-based drought disaster risk reduction and break away from piecemeal and costly crisis response, which often comes too late to avert death, displacement and destruction.

The meeting on March 11-15 was organized by the UNCCD, the World Meteorological Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization. It brought together more than 300 government decision makers, development agencies, and scientists.

They concluded that innovations now exist for national and regional drought monitoring, early warning systems and risk-based responses as well as mitigation and coping strategies.

This month in Bonn, scientists, governments and civil society organizations will meet to carry out the first ever comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of desertification, land degradation and drought.

For the first time, governments will provide concrete data on the status of poverty and of land cover in the areas affected by desertification in their countries.

The UN Environment Programme says that according to the most recent national reports, desertification affects 168 countries.

Copyright Environment News Service (ENS) 2013. All rights reserved.

© 2013, Environment News Service. All rights reserved. Content may be quoted only with proper attribution and a direct link to the original article. Full reproduction is prohibited.